Statement by SEC Staff:

A Race to the Top: International Regulatory Reform Post Sarbanes-Oxley1

by

Ethiopis Tafara2

Director, Office of International Affairs

U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission

International Financial Law Review

September 2006

This article identifies the widespread global adoption of the major provisions of the Sarbanes Oxley Act of 2002 (SOX). The global adoption of these provisions is interesting on a number of counts. As is the case in many industries today, the US financial services industry competes on a global scale. From this competitive vantage point, the industry has discovered — and at times loudly proclaimed — that their products and services are inextricably bundled with (or, depending on one's perspective, burdened by) the domestic regulatory framework in which they operate. In particular, it has been argued by some that SOX may have generated regulations that are not cost justified, and that this may have created certain competitive disadvantages for the US market.

To be sure, given the technological revolution in connectivity, investors and issuers can largely meet in the jurisdiction of their choosing. Investors as well as issuers have choices about where to invest, where to raise capital and where secondary trading is to occur. In other words, they have some choice about which regulatory safeguards (and associated enforcement efforts) they conduct their financial activities under. Moreover, important economic characteristics (such as cost and risk) of financial services and products are affected by the particular (and inevitably costly) regulatory safeguards associated with any given jurisdiction, as backed up by the enforcement efforts in that jurisdiction. As a consequence, domestic regulations may admittedly have an impact on the global competitiveness of financial services and products, for good or potentially for ill.

Lawmakers and securities regulators around the world worry about what the impact of this increasing competitive pressure will be on regulatory quality, and whether it serves the public interest. They ask whether competitive pressures on regulators will inevitably lead to what former SEC Chairman William Cary termed a "race to the bottom."3 That is, will securities regulators — in their frantic efforts to attract issuers — de-regulate to the point where there are inadequate protections for investors? Or, alternatively, is it possible that the pressures associated with this so-called "jurisdictional competition" could lead to improved protections for investors, and, in fact, constitute a healthy pressure on various regulatory frameworks around the world? In fact, for the most part regulators around the globe do not act as if they are in a race to the bottom. They cooperate extensively with one another on cross-border enforcement efforts, and this cooperation has been growing. In addition, they regularly share information on best regulatory practices through both formal and informal dialogues and technical consultations.

Economists (who by their nature tend to be attracted to competition) offer an alternative theory to the "race to the bottom." They argue that while issuers might superficially be attracted to a jurisdiction where regulation falls short in terms of investor protection, investors will not be attracted to that jurisdiction unless they are compensated for the more modest investor protections (and the extra risk associated therewith) by a higher expected rate of return. As a consequence, the cost of capital for the issuers in jurisdictions with more modest protections will be higher than it would be where there were cost-justified investor protections. On the other hand, if a jurisdiction is beyond the point of cost-justified regulation (i.e., it has "too much" regulation), the cost of this excess regulation will be borne directly by investors and issuers, and they both will want to avoid such a jurisdiction. In sum, according to the economists both issuers and investors have an incentive to "meet" one another in a jurisdiction that has cost-justified investor protection. It follows that, in order to attract investors and issuers, the best strategy for jurisdictions is to provide investor protections that are cost-justified — no more and no less. That is, the race may not to the bottom, but rather to what economists call optimality.

While the reality may be a bit more complicated than either a race to the bottom or a race to optimality would suggest, the global adoption of the major provisions of SOX may shed some light on these and other issues. First, and most obviously, it suggests that these major provisions, in and of themselves, have not competitively disadvantaged US markets, simply by virtue of the fact that they have been widely adopted elsewhere. Second, it suggests that (at least in terms of these major provisions of SOX) there does not appear to be a race to the bottom among regulators globally, since these provisions are not without substantial costs and do provide enhanced investor protections. Third, if one believes that regulators are in fact in a race to optimality, as some economists suggest, then the global adoption of the major provisions of SOX suggests that these provisions, at least in broad outline, have been deemed to be cost-justified by authorities covering the bulk of the world's market capitalization. That doesn't necessarily imply that they are, in fact, cost justified — but it is an interesting confluence of regulatory opinion.

Of course, the adoption of these provisions — writ large — does not imply that all regulators have operationalized them with the same efficiency and cost effectiveness. As everyone in the financial industry understands, the devil (and perhaps the angels) are in the details. I understand that there is much to debate as well as possibly refine in terms of the execution of these provisions. I leave those admittedly crucial issues to another day and to others. Nor am I necessarily arguing that the US adoption of SOX was the cause of the broad adoption of these provisions. The US was merely an early mover with respect to a series of gaps that began to appear in the protections to investors provided by various global regulatory frameworks. Rather, here I restrict myself to the modest observation and identification of the global adoption of certain major provisions of SOX.

BACKGROUND

Passed by Congress in response to the financial scandals of Enron and Worldcom, SOX was designed to mitigate the recurrence of such scandals and restore investor confidence in the financial markets. It sought to do this by, among other things, strengthening auditor independence, augmenting internal control requirements with respect to financial reporting, and introducing independent oversight over the audit profession through the creation of the Public Company Accounting Oversight Board (PCAOB).

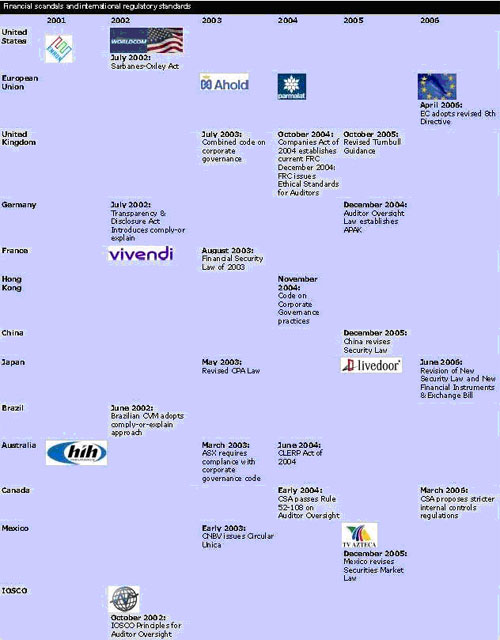

This overview traces the extent to which the key provisions of SOX have been reflected in recent regulatory reforms in other large capital markets in Asia, Europe and Latin America, particularly in the UK, Germany, France, Hong Kong, China, Japan, Brazil, Australia, Canada and Mexico. Indeed, in some cases, passage of SOX has led to a reinvigoration of regulations or oversight bodies in other countries that, while predating the Act, had failed to garner international attention.

The overview focuses on the following four major components of SOX: the establishment of a public oversight body independent of the audit profession; the strengthening of auditor independence; the strengthening of audit committee requirements; and the augmentation of internal control requirements with respect to financial reporting.

AUDITOR OVERSIGHT BODIES

In the US, SOX created the PCAOB, a private sector, non-profit corporation, for the purpose of providing independent oversight to the audit profession in the wake of Enron and other financial scandals. The PCAOB's main functions include registering public accounting firms, promulgating auditing standards, inspecting registered public accounting firms, and enforcing auditing standards.

The concept of independent regulation of the accounting profession has gained ground abroad as well. A number of jurisdictions have established independent auditor oversight authorities to regulate the audit profession. However, the scope of regulatory oversight differs among foreign auditor oversight authorities, in particular with respect to their functions, their independence, and the degree of interaction with the audit profession and governmental agencies.

Trends in regulatory approaches to oversight among the larger markets can be summarized in the following categories and examples:

Independent statutory body and a governmental agency

As described above, SOX provided for this approach, whereby an independent statutory body (the PCAOB) assumes the direct regulatory functions of standards-setting, registration, inspections and enforcement. The PCAOB, however, remains subject to oversight by a government agency (the SEC), which also maintains an independent enforcement and rulemaking authority over public company audits.

Independent statutory body and a self-regulatory professional body

In the UK, by contrast, auditor oversight is divided between an independent statutory body and a self-regulatory professional body. The independent Financial Reporting Council (FRC) regulates audit services, while the registration of auditors is left to the professional bodies, with the FRC providing oversight. The proposed regulatory framework in Hong Kong also adopts this approach; however in contrast to the UK, regulatory functions are vested primarily with a professional body, as opposed to an independent body. The Hong Kong Financial Reporting Council investigates audit irregularities while the Hong Kong Institute of Certified Public Accountants performs all other regulatory functions, namely registration, standard setting and enforcement.

Independent statutory body, governmental agencies and self-regulation

In Australia, Canada, France, Germany and Japan, the regulatory approach might best be described as "all of the above." In Australia, the recently established independent statutory body, the Australian Auditing and Assurance Standards Board, has authority for setting standards and is subject to oversight by another independent statutory body, the Financial Reporting Council. The investigation and registration of auditors is conducted by a governmental agency, the Australian Securities and Investments Commission, while another government entity, the Companies Auditors and Liquidators Disciplinary Board, is charged with the discipline of auditors. Additionally, professional bodies continue to impose their own standards on members and retain some disciplinary powers.

In Canada, auditing standards are set by a professional body, which is subject to oversight by the independent Auditing and Assurance Standards Oversight Council. Auditing standards are also subject to oversight by provincial securities regulators, some of which have explicit statutory authority to establish standards that must be followed by auditors of public companies. The other principal regulatory functions — registration, inspection and enforcement — are performed by another independent body, the Canadian Public Accountability Board.

France, Germany and Japan have allowed professional auditing and accounting bodies to continue self-regulating, while establishing an independent statutory body to oversee such self-regulation. In all three markets, though, governmental agencies continue to have an enforcement mandate in the event of serious audit violations.

Governmental agencies and a professional body

Some jurisdictions, particularly Brazil and Mexico, depend on self-regulation as the primary mechanism for setting auditing standards, with governmental agencies exercising the regulatory functions. The Mexican Financial Authorities and industry groups, however, are currently in discussion regarding the establishment of an independent oversight body.

Governmental agencies

In China, regulation of public company audit firms and audit standards are the sole province of governmental agencies.

INDEPENDENCE OF AUDITOR OVERSIGHT BODIES

While there is now widespread agreement that auditor oversight bodies should be independent of the industry they oversee, jurisdictions approach the notion of independence from different perspectives. In the US context, SOX established that independence from the profession was to completely replace auditor self-regulation, and SOX requires that while two former auditors may serve on the PCAOB, no PCAOB member may be a current practitioner. Even more strict, Germany now prohibits someone from being a member of the oversight authority if he or she has been a member of the accounting profession within the past five years. France, however, allows up to three current practitioners to serve on the board of its oversight body. One common feature among the large markets, however, is that, at a minimum, a majority of members auditor oversight bodies should not be current or former auditors.

Strengthening Auditor Independence

The strengthening of auditor independence to reduce conflicts of interest was another key component of SOX. It achieved this principally by:

- Prohibiting the provision of specific non-audit services by a public company's auditor;

- Imposing mandatory audit partner rotation; and

- Imposing temporary restrictions on audit firms from auditing a company whose management includes former employees of the firm.

Non-Audit Services

SOX recognized that the growing importance of non-audit service fees to audit firms was contributing to auditors' weakening ability to act as independent gatekeepers against financial frauds. This issue was addressed by prescribing prohibitions on the provision of a specific list of non-audit services, and by requiring all other non-audit services to be pre-approved by a public company's audit committee. Such a "rules-based" approach was internationally noted by IOSCO, which issued a statement in October 2002 that supports the analysis of threats to independence developed by the International Federation of Accountants (IFAC), but also recognizes that rules are one way to address cases where the risks to independence, either in fact or appearance, are too great.

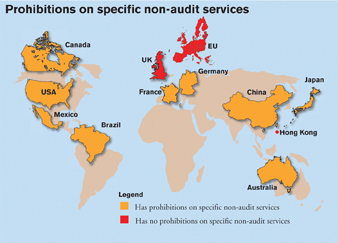

Other large capital markets have recognized the restriction of non-audit services as an important tool to bolster auditor independence. While certain jurisdictions differ from SOX in that they use a "principles-based" regulatory framework to address these concerns, others, including Mexico, Germany, China and Japan, have begun introducing prohibitions on specific services that are akin to SOX's rules-based approach. Furthermore, an increasing number of jurisdictions, including France, Australia and Canada, have passed reforms that combine a principles-based approach to general threats to auditor independence (and their corresponding safeguards) with specific prohibitions on certain particularly problematic non-audit services.

By contrast, jurisdictions that favor a solely principles-based approach include Hong Kong and the UK. Such jurisdictions often supplement these principles by requiring enhanced disclosure of non-audit services with the UK company law, for example, mandating disclosure of each type of non-audit service provided and a breakdown of the cost of each. Interestingly, while the EU's revised 8th Directive takes a specifically principles-based approach, individual Member States (such as Germany and France) nonetheless appear to believe that principles alone may be insufficient for certain specific (and particularly conflicts-prone) non-audit services.

Audit Partner Rotation

SOX further reinforced auditor independence by requiring the lead audit partner (who has primary responsibility for the audit) and the partner responsible for reviewing the audit to rotate off a client's audit after five consecutive years. Since then, the EU, UK, France, Hong Kong, China, Japan, Australia, Canada and Mexico have all passed reforms requiring mandatory audit partner rotation. Other countries, such as Italy, had previously adopted similar provisions on audit partner rotation or, in Brazil, even required rotation of the audit firm itself.

Audit team recruitment

Seeking to reduce conflicts of interest between auditors and management of the audited company, SOX bars audit firms from performing any audit service if the CEO, CFO, controller or chief accounting officer of the company was employed by that audit firm and participated in any capacity in the audit of that company in the preceding year. Reducing such conflicts of interest has also featured among reforms in other large capital markets, with the EU, UK, France, Hong Kong, Japan, Australia and Canada all introducing similar restrictions since the passage of SOX.

While all of these jurisdictions share this same objective, their regulatory approaches differ with respect to whom the temporary restriction falls upon in order to reduce potential conflicts of interest. Under the approach taken in SOX, a temporary restriction is imposed on the audit firm whose team member has joined the client's management, in that the firm cannot audit the client for one year. The law does not prevent the individual audit team member from joining the client. The UK, Hong Kong and Canada have also opted for this approach, with varying time-periods of restriction on the audit firm. Under the second approach, the restriction falls on the individual audit team member, in that the individual cannot join the audit client's management until a set 'cooling-off' period elapses, during which he or she cannot participate in the client's audit. This approach is taken by France, Japan, Australia and in the EU's 8th Directive. Australia has added a unique provision forbidding an audit team member from joining a client's management in which there already is another former audit team member from the same firm.

CORPORATE GOVERNANCE AUDIT COMMITTEE REQUIREMENTS

Another area of significant reform introduced by SOX was strengthening corporate board oversight of management and the independent auditor by enhancing the powers and responsibilities of the board audit committee. In particular, SOX charged such committees with:

- Taking responsibility for appointment, compensation and oversight of the company's auditor;

- Pre-approving all auditing and non-audit services provided by the auditor;

- Receiving reports from the auditor regarding critical accounting policies and practices as well as alternative treatments of financial information; and

- Establishing procedures for receipt of complaints, including whistleblower procedures, regarding accounting, internal controls and auditing issues.

Just as significantly, SOX required that all board audit committee members be independent directors. Further, SOX requires a public company to disclose whether its audit committee includes a financial expert.

While in some ways the most controversial part of SOX (federal securities law in the United States up until then focusing mostly on disclosure rather than on corporate governance practices), since 2002 several other capital markets have introduced similar corporate governance reforms that require public companies to establish audit committees, strengthen their independence and expertise, and increase their powers.

The Audit Committee Requirement

Since passage of SOX, the number of large capital markets that require a public company to have an audit committee has increased. The EU, Canada, Mexico, Australia, Hong Kong and Brazil now mandate that public companies have an audit committee or an equivalent body as part of their corporate structure. Likewise, the UK and Germany impose an audit committee requirement on a comply-or-explain basis. In France, Japan and China, however, such committees are voluntary.

Independence and Expertise Requirement

SOX's requirement that all audit committee members be independent has been mirrored by reforms in other large capital markets, with most countries strengthened independence requirements in recent years. The UK, Hong Kong, Australia, Canada and Mexico have introduced reforms since 2002 requiring that all members be independent, while Brazil had requirements predating SOX that mandated that fiscal boards be comprise of only independent members. France, China and Japan, on the other hand, require that a majority of audit committee members be independent. Less stringent requirements are in place in Germany, where only the chairperson must be independent, and in the EU's 8th Directive, which requires that, at a minimum, one member be independent. Variants of SOX's requirement that a public company disclose whether a financial expert is part of the audit committee are also featured among reforms in the UK, Hong Kong, Germany, China, Brazil, Australia and with the EU's 8th Directive.

Strengthening of Audit Committee's Powers and Responsibilities

One of the key audit committee functions prescribed by SOX was an enhanced role in ensuring auditor independence by requiring such committees to pre-approve all non-prohibited non-audit services provided by the auditor. Canada and Mexico have since enacted the same requirement, while the French Corporate Governance of Listed Corporations recommends this practice. Moreover, several other markets, including the EU, UK, Germany, Hong Kong and Australia, have charged audit committees with providing some form of oversight over the auditor's independence and provision of non-audit services.

SOX also tasked audit committees with the responsibility for appointing and setting compensation for a company's auditor. While many jurisdictions have traditionally vested the power to appoint the company's auditor with a shareholder vote based on a proposal from the board of directors, audit committees have been given an increasingly enhanced role in this process. The EU's 8th Directive, the UK, France, Hong Kong, China, Japan, Australia and Canada have all recently required audit committees to recommend an auditor to the board, and in some jurisdictions, such as the EU and Japan, the board must base its shareholder proposal on this recommendation. Additionally, the UK, Germany, Hong Kong, Japan and Brazil have adopted provisions similar to those in SOX that require auditor's remuneration to be set by the audit committee.

INTERNAL CONTROLS

SOX places on public companies three principal requirements for ensuring the adequacy of internal controls over financial reporting:

- Management must state in the annual report that it is responsible for establishing and maintaining an adequate internal control system;

- Management must publish in the annual report an assessment of the effectiveness of the internal control system; and

- The auditor of the annual report must attest to and report on management's assessment of the internal control system.

These three main provisions have basic equivalents in all jurisdictions covered in this survey. A number of jurisdictions — including France and Japan — have established rules-based internal controls requirements through legislation, with the Japanese and French legislation closely resembling the internal controls requirements of SOX. The revised Security Law in China will follow upon the internal controls requirements of SOX after the China Securities Regulatory Commission (CSRC) has completed the law's implementing regulations. Canada is also moving towards a rules-based approach, founded on new Canadian Securities Administrators (CSA) regulations.

Many jurisdictions have opted for a comply-or-explain approach with varying degrees of strength. The comply-or-explain requirement generally operates through an exchange listing rule that obligates companies to comply with the provisions of a corporate governance code or else explain non-compliance. Jurisdictions adopting this approach include the UK, Australia, Germany, and Hong Kong, with proposed revisions to EU Company Directives also strongly leaning in this direction. The German approach to internal control is mixed in this regard as the comply-or-explain requirement has been written directly into the German Company Law. Hong Kong, by contrast, prescribes a content standard ("substantive, not formalistic") for disclosures that explain non-compliance with code provisions. The European Corporate Governance Forum, a body set up by the European Commission that examines best practices in EU Member States, has also stressed the importance of requiring substantive disclosures to maintain the effectiveness of the comply-or-explain approach to internal control reporting.

A few jurisdictions have a wholly voluntary regime that encourages compliance with codes of corporate governance, but does not require management to establish or report on internal control systems. In such jurisdictions, the securities regulator or stock exchange publishes a corporate governance code that calls upon listed companies to follow the internal control norms that the code outlines. Mexico follows this model, but listing rules in Mexico impose the additional requirement that listed companies report to the exchange on the extent to which they have followed the provisions of the code. The Brazilian Institute of Corporate Governance (IBGC) also has issued a code that operates on a purely voluntary basis.

Establishing and Maintaining an Internal Control System

SOX requires that management state in the annual report that it is responsible for establishing and maintaining a system of internal controls, essentially ensuring that an internal controls system is in place by explicitly identifying management as accountable for any inadequacies. CSA regulations entering into effect in 2008 in Canada will require a similar statement of responsibility from the CEO and CFO. Similarly, Germany, Japan, and China now have laws that require that a company have an adequate internal controls system, with Germany's Stock Corporation Law actually prescribing the internal controls systems that a company must have in place. Japan's revised Company Law and new Financial Instruments and Exchange Bill contain a framework for the establishment and maintenance by management of the internals control system, while China's revised Security Law purports to require that companies also have an internal controls system.

France, although also adopting a legislative, rules-based approach, does not require an explicit statement from management or the board of its responsibility for the internal controls system. Rather, since France requires a managerial assessment of the issuer's internal controls, a managerial statement of responsibility for these internal controls is considered implied.

Other jurisdictions focus on dividing responsibilities for establishing and maintaining the internal controls system between the board and the management of the company. The Australian Corporate Governance Code, established under the auspices of the ASX, recommends that the board formulate policies on internal controls and that management establish the system of internal controls based on these policies. Mexico's code similarly recommends that the board approve guidelines for internal controls for subsequent implementation by management, and the new Securities Market Law will make this division of responsibilities mandatory.

Company Reporting on Internal Controls Procedures

SOX requires that management publish in its annual report an assessment of the effectiveness of the internal controls system. Such internal controls reporting requirements have found the widest acceptance among the jurisdictions covered in this survey. Australian listing rules include further measures that, on a comply-or-explain basis, require management to publish on the company website internal controls policies and descriptions of the system of internal controls. Canada's new regulations further require that management's report identify the framework against which the internal controls system is being evaluated. The French AMF has issued reporting guidance that contains content standards for internal controls reports, suggesting that management's evaluations focus on disclosing information that is relevant in terms of the business risks that the company faces.

At the same time, some jurisdictions stop short of requiring reporting of an assessment of the adequacy of the internal controls system. Revised EU Company Directives, for instance, set as a minimum standard that management provide a description of the company's internal controls in the annual report. No assessment of this description is mandated. Likewise, Hong Kong's corporate governance code, which operates on a comply-or-explain basis, requires the board to inform shareholders that it has completed an annual review of the effectiveness of the company's internal controls, and recommends that this review be published in a corporate governance section of the annual report.

External Audits of Internal Controls

SOX requires that the auditor of a company's annual report attest to and report on management's assessment of the company's internal controls. Although this aspect of Section 404 has been controversial, several other jurisdictions have adopted some variant of this requirement. Among those jurisdictions that have adopted a rules-based approach to internal control, China, France and Japan also require the auditor to report on management's assessment of the internal controls system. The revised Japanese laws require the auditor to make this evaluation with reference to the COSO framework, a set of internal control evaluation procedures developed by the Committee of Sponsoring Organizations of the Treadway Commission (COSO). French regulations, however, do not prescribe the manner in which the auditor evaluation is to be conducted. Although earlier proposed Canadian regulations had included a provision on auditor evaluation of management's internal controls report, the CSA ultimately declined to adopt this provision.

German and Mexican codes of corporate governance require, on a comply-or-explain basis, that the auditor issue a public report on management's internal control assessment. By contrast, the UK requirement, also operating on a comply-or-explain basis, only requires that an auditor report by exception if management's assessment is entirely unsupportable or inappropriate in light of the auditor's understanding of the company's internal control process.

Endnotes

http://www.sec.gov/news/speech/2006/spch091106et.htm