0000858470☒FALSE2022FYFALSEP3Yhttp://fasb.org/us-gaap/2022#OtherNonoperatingIncomeExpensehttp://fasb.org/us-gaap/2022#DerivativeAssetsCurrent http://fasb.org/us-gaap/2022#OtherAssetsNoncurrenthttp://fasb.org/us-gaap/2022#DerivativeAssetsCurrent http://fasb.org/us-gaap/2022#OtherAssetsNoncurrenthttp://fasb.org/us-gaap/2022#DerivativeLiabilitiesCurrenthttp://fasb.org/us-gaap/2022#DerivativeLiabilitiesCurrentP3Y3333http://fasb.org/us-gaap/2022#OtherAssetsNoncurrenthttp://fasb.org/us-gaap/2022#OtherAssetsNoncurrenthttp://fasb.org/us-gaap/2022#AccruedLiabilitiesCurrenthttp://fasb.org/us-gaap/2022#AccruedLiabilitiesCurrenthttp://fasb.org/us-gaap/2022#AccruedLiabilitiesCurrenthttp://fasb.org/us-gaap/2022#AccruedLiabilitiesCurrenthttp://fasb.org/us-gaap/2022#OtherLiabilitiesNoncurrenthttp://fasb.org/us-gaap/2022#OtherLiabilitiesNoncurrenthttp://fasb.org/us-gaap/2022#OtherLiabilitiesNoncurrenthttp://fasb.org/us-gaap/2022#OtherLiabilitiesNoncurrent00008584702022-01-012022-12-3100008584702022-06-30iso4217:USD00008584702023-02-24xbrli:shares00008584702022-12-3100008584702021-12-31iso4217:USDxbrli:shares0000858470us-gaap:NaturalGasProductionMember2022-01-012022-12-310000858470us-gaap:NaturalGasProductionMember2021-01-012021-12-310000858470us-gaap:NaturalGasProductionMember2020-01-012020-12-310000858470us-gaap:OilAndCondensateMember2022-01-012022-12-310000858470us-gaap:OilAndCondensateMember2021-01-012021-12-310000858470us-gaap:OilAndCondensateMember2020-01-012020-12-310000858470srt:NaturalGasLiquidsReservesMember2022-01-012022-12-310000858470srt:NaturalGasLiquidsReservesMember2021-01-012021-12-310000858470srt:NaturalGasLiquidsReservesMember2020-01-012020-12-3100008584702021-01-012021-12-3100008584702020-01-012020-12-310000858470cog:OtherRevenuesMember2022-01-012022-12-310000858470cog:OtherRevenuesMember2021-01-012021-12-310000858470cog:OtherRevenuesMember2020-01-012020-12-3100008584702020-12-3100008584702019-12-310000858470us-gaap:CommonStockMember2019-12-310000858470us-gaap:TreasuryStockCommonMember2019-12-310000858470us-gaap:AdditionalPaidInCapitalMember2019-12-310000858470us-gaap:AccumulatedOtherComprehensiveIncomeMember2019-12-310000858470us-gaap:RetainedEarningsMember2019-12-310000858470us-gaap:RetainedEarningsMember2020-01-012020-12-310000858470us-gaap:CommonStockMember2020-01-012020-12-310000858470us-gaap:AdditionalPaidInCapitalMember2020-01-012020-12-310000858470us-gaap:AccumulatedOtherComprehensiveIncomeMember2020-01-012020-12-310000858470us-gaap:CommonStockMember2020-12-310000858470us-gaap:TreasuryStockCommonMember2020-12-310000858470us-gaap:AdditionalPaidInCapitalMember2020-12-310000858470us-gaap:AccumulatedOtherComprehensiveIncomeMember2020-12-310000858470us-gaap:RetainedEarningsMember2020-12-310000858470us-gaap:RetainedEarningsMember2021-01-012021-12-310000858470us-gaap:CommonStockMember2021-01-012021-12-310000858470us-gaap:AdditionalPaidInCapitalMember2021-01-012021-12-310000858470us-gaap:TreasuryStockCommonMember2021-01-012021-12-310000858470us-gaap:AccumulatedOtherComprehensiveIncomeMember2021-01-012021-12-310000858470us-gaap:CommonStockMember2021-12-310000858470us-gaap:TreasuryStockCommonMember2021-12-310000858470us-gaap:AdditionalPaidInCapitalMember2021-12-310000858470us-gaap:AccumulatedOtherComprehensiveIncomeMember2021-12-310000858470us-gaap:RetainedEarningsMember2021-12-310000858470us-gaap:RetainedEarningsMember2022-01-012022-12-310000858470us-gaap:CommonStockMember2022-01-012022-12-310000858470us-gaap:AdditionalPaidInCapitalMember2022-01-012022-12-310000858470us-gaap:TreasuryStockCommonMember2022-01-012022-12-310000858470us-gaap:AccumulatedOtherComprehensiveIncomeMember2022-01-012022-12-310000858470us-gaap:CommonStockMember2022-12-310000858470us-gaap:TreasuryStockCommonMember2022-12-310000858470us-gaap:AdditionalPaidInCapitalMember2022-12-310000858470us-gaap:AccumulatedOtherComprehensiveIncomeMember2022-12-310000858470us-gaap:RetainedEarningsMember2022-12-31cog:Segmentcog:Institution0000858470srt:MinimumMember2022-01-012022-12-310000858470srt:MaximumMember2022-01-012022-12-310000858470us-gaap:SalesRevenueNetMemberus-gaap:CustomerConcentrationRiskMember2022-01-012022-12-31cog:Customer0000858470cog:CustomerOneConcentrationRiskMemberus-gaap:SalesRevenueNetMemberus-gaap:CustomerConcentrationRiskMember2022-01-012022-12-31xbrli:pure0000858470cog:CustomerTwoConcentrationRiskMemberus-gaap:SalesRevenueNetMemberus-gaap:CustomerConcentrationRiskMember2022-01-012022-12-310000858470us-gaap:SalesRevenueNetMemberus-gaap:CustomerConcentrationRiskMember2021-01-012021-12-310000858470us-gaap:SalesRevenueNetMemberus-gaap:CustomerConcentrationRiskMember2020-01-012020-12-310000858470cog:CustomerOneConcentrationRiskMemberus-gaap:SalesRevenueNetMemberus-gaap:CustomerConcentrationRiskMember2020-01-012020-12-310000858470cog:CustomerTwoConcentrationRiskMemberus-gaap:SalesRevenueNetMemberus-gaap:CustomerConcentrationRiskMember2020-01-012020-12-310000858470cog:CustomerNumberThreeMemberus-gaap:SalesRevenueNetMemberus-gaap:CustomerConcentrationRiskMember2020-01-012020-12-310000858470cog:CimarexMemberus-gaap:CommonStockMember2021-10-010000858470cog:CimarexMember2022-01-012022-12-310000858470cog:CimarexMembercog:CimarexMember2021-10-010000858470cog:CimarexMemberus-gaap:CommonStockMember2021-10-012021-10-010000858470us-gaap:EmployeeStockOptionMembercog:CimarexMember2021-10-010000858470cog:CimarexMemberus-gaap:RestrictedStockMember2021-10-010000858470cog:CimarexMember2021-10-012021-10-010000858470cog:CimarexMember2021-10-010000858470cog:CimarexMember2021-10-012021-12-310000858470cog:CimarexMember2021-01-012021-12-310000858470cog:CimarexMember2021-12-310000858470cog:ProvedOilAndGasPropertiesMember2022-12-310000858470cog:ProvedOilAndGasPropertiesMember2021-12-310000858470cog:UnprovedOilAndGasPropertiesMember2022-12-310000858470cog:UnprovedOilAndGasPropertiesMember2021-12-310000858470cog:GatheringAndPipelinesMember2022-12-310000858470cog:GatheringAndPipelinesMember2021-12-310000858470cog:LandBuildingsAndOtherEquipmentMember2022-12-310000858470cog:LandBuildingsAndOtherEquipmentMember2021-12-310000858470us-gaap:SeniorNotesMembercog:SixPointFiveOnePercentageWeightedAveragePrivatePlacementSeniorNotesMember2022-12-310000858470us-gaap:SeniorNotesMembercog:SixPointFiveOnePercentageWeightedAveragePrivatePlacementSeniorNotesMember2021-12-310000858470cog:FivePointFiveEightPercentageWeightedAveragePrivatePlacementSeniorNotesMemberus-gaap:SeniorNotesMember2022-12-310000858470cog:FivePointFiveEightPercentageWeightedAveragePrivatePlacementSeniorNotesMemberus-gaap:SeniorNotesMember2021-12-310000858470cog:ThreePointSixtyFivePercentageWeightedAveragePrivatePlacementSeniorNotesMemberus-gaap:SeniorNotesMember2022-12-310000858470cog:ThreePointSixtyFivePercentageWeightedAveragePrivatePlacementSeniorNotesMemberus-gaap:SeniorNotesMember2021-12-310000858470us-gaap:SeniorNotesMembercog:FourPointThreeSevenFivePercentageSeniorNotesDueJune12024Member2022-12-310000858470us-gaap:SeniorNotesMembercog:FourPointThreeSevenFivePercentageSeniorNotesDueJune12024Member2021-12-310000858470us-gaap:SeniorNotesMembercog:ThreePointNineZeroPercentageSeniorNotesDueMay152027Member2022-12-310000858470us-gaap:SeniorNotesMembercog:ThreePointNineZeroPercentageSeniorNotesDueMay152027Member2021-12-310000858470us-gaap:SeniorNotesMembercog:FourPointThreeSevenFivePercentageSeniorNotesDueMarch152029Member2022-12-310000858470us-gaap:SeniorNotesMembercog:FourPointThreeSevenFivePercentageSeniorNotesDueMarch152029Member2021-12-310000858470us-gaap:LineOfCreditMemberus-gaap:RevolvingCreditFacilityMember2022-12-310000858470us-gaap:LineOfCreditMemberus-gaap:RevolvingCreditFacilityMember2021-12-310000858470cog:ThreePointSixtyFivePercentageWeightedAveragePrivatePlacementSeniorNotesMemberus-gaap:SeniorNotesMembersrt:ScenarioForecastMember2024-09-012024-09-300000858470cog:ThreePointSixtyFivePercentageWeightedAveragePrivatePlacementSeniorNotesMemberus-gaap:SeniorNotesMembersrt:ScenarioForecastMember2026-09-012026-09-300000858470cog:CimarexMemberus-gaap:SeniorNotesMember2022-12-310000858470us-gaap:SeniorNotesMembercog:FourPointThreeSevenFivePercentageSeniorNotesDueJune12024Member2021-10-010000858470cog:ThreePointNineZeroPercentageSeniorNotesMemberus-gaap:SeniorNotesMember2021-10-010000858470us-gaap:SeniorNotesMembercog:FourPointThreeSevenFivePercentageSeniorNotesDueMarch152029Member2021-10-010000858470us-gaap:SeniorNotesMember2021-10-010000858470us-gaap:SeniorNotesMembercog:SixPointFiveOnePercentageWeightedAveragePrivatePlacementSeniorNotesMember2022-01-012022-12-310000858470cog:FivePointFiveEightPercentageWeightedAveragePrivatePlacementSeniorNotesMemberus-gaap:SeniorNotesMember2022-01-012022-12-310000858470us-gaap:SeniorNotesMember2022-01-012022-12-31cog:fiscal_period0000858470us-gaap:SeniorNotesMembercog:ExistingCimarexNotesMember2022-12-310000858470us-gaap:SeniorNotesMembercog:FourPointThreeSevenFivePercentageSeniorNotesDueJune12024Member2022-01-012022-12-310000858470us-gaap:LineOfCreditMemberus-gaap:RevolvingCreditFacilityMember2021-09-162021-09-160000858470srt:MinimumMemberus-gaap:LineOfCreditMemberus-gaap:RevolvingCreditFacilityMemberus-gaap:LondonInterbankOfferedRateLIBORMember2019-04-222019-04-220000858470us-gaap:LineOfCreditMemberus-gaap:RevolvingCreditFacilityMembersrt:MaximumMemberus-gaap:LondonInterbankOfferedRateLIBORMember2019-04-222019-04-220000858470srt:MinimumMemberus-gaap:LineOfCreditMemberus-gaap:RevolvingCreditFacilityMembercog:AlternateBaseRateMember2019-04-222019-04-220000858470us-gaap:LineOfCreditMemberus-gaap:RevolvingCreditFacilityMembercog:AlternateBaseRateMembersrt:MaximumMember2019-04-222019-04-220000858470srt:MinimumMemberus-gaap:LineOfCreditMemberus-gaap:RevolvingCreditFacilityMember2019-04-222019-04-220000858470us-gaap:LineOfCreditMemberus-gaap:RevolvingCreditFacilityMembersrt:MaximumMember2019-04-222019-04-220000858470cog:WahaGasCollarsMembersrt:ScenarioForecastMember2023-01-012023-03-31utr:MMBTU0000858470cog:WahaGasCollarsMembersrt:ScenarioForecastMember2023-04-012023-06-300000858470cog:WahaGasCollarsMembersrt:ScenarioForecastMember2023-07-012023-09-300000858470cog:WahaGasCollarsMembersrt:ScenarioForecastMember2023-10-012023-12-310000858470cog:WahaGasCollarsMembersrt:ScenarioForecastMember2023-03-31iso4217:USDutr:MMBTU0000858470cog:WahaGasCollarsMembersrt:ScenarioForecastMember2023-06-300000858470cog:WahaGasCollarsMembersrt:ScenarioForecastMember2023-09-300000858470cog:WahaGasCollarsMembersrt:ScenarioForecastMember2023-12-310000858470srt:ScenarioForecastMembercog:NYMEXCollarsMember2023-01-012023-03-310000858470srt:ScenarioForecastMembercog:NYMEXCollarsMember2023-04-012023-06-300000858470srt:ScenarioForecastMembercog:NYMEXCollarsMember2023-07-012023-09-300000858470srt:ScenarioForecastMembercog:NYMEXCollarsMember2023-10-012023-12-310000858470srt:ScenarioForecastMembercog:NYMEXCollarsMember2023-03-310000858470srt:ScenarioForecastMembercog:NYMEXCollarsMember2023-06-300000858470srt:ScenarioForecastMembercog:NYMEXCollarsMember2023-09-300000858470srt:ScenarioForecastMembercog:NYMEXCollarsMember2023-12-310000858470cog:WTIOilCollarsMembersrt:ScenarioForecastMember2023-01-012023-03-31utr:MBoe0000858470cog:WTIOilCollarsMembersrt:ScenarioForecastMember2023-04-012023-06-300000858470cog:WTIOilCollarsMembersrt:ScenarioForecastMember2023-03-31iso4217:USDutr:MBbls0000858470cog:WTIOilCollarsMembersrt:ScenarioForecastMember2023-06-300000858470cog:WTIMidlandOilBasisSwapsMembersrt:ScenarioForecastMember2023-01-012023-03-310000858470cog:WTIMidlandOilBasisSwapsMembersrt:ScenarioForecastMember2023-04-012023-06-300000858470cog:WTIMidlandOilBasisSwapsMembersrt:ScenarioForecastMember2023-03-310000858470cog:WTIMidlandOilBasisSwapsMembersrt:ScenarioForecastMember2023-06-300000858470us-gaap:NondesignatedMemberus-gaap:CommodityContractMember2022-12-310000858470us-gaap:NondesignatedMemberus-gaap:CommodityContractMember2021-12-310000858470cog:GasContractsMember2022-01-012022-12-310000858470cog:GasContractsMember2021-01-012021-12-310000858470cog:GasContractsMember2020-01-012020-12-310000858470cog:OilContractsMember2022-01-012022-12-310000858470cog:OilContractsMember2021-01-012021-12-310000858470cog:OilContractsMember2020-01-012020-12-310000858470us-gaap:FairValueMeasurementsRecurringMemberus-gaap:FairValueInputsLevel1Member2022-12-310000858470us-gaap:FairValueMeasurementsRecurringMemberus-gaap:FairValueInputsLevel2Member2022-12-310000858470us-gaap:FairValueInputsLevel3Memberus-gaap:FairValueMeasurementsRecurringMember2022-12-310000858470us-gaap:FairValueMeasurementsRecurringMember2022-12-310000858470us-gaap:FairValueMeasurementsRecurringMemberus-gaap:FairValueInputsLevel1Member2021-12-310000858470us-gaap:FairValueMeasurementsRecurringMemberus-gaap:FairValueInputsLevel2Member2021-12-310000858470us-gaap:FairValueInputsLevel3Memberus-gaap:FairValueMeasurementsRecurringMember2021-12-310000858470us-gaap:FairValueMeasurementsRecurringMember2021-12-31cog:Impaired_Asset_And_Liabilty0000858470us-gaap:CarryingReportedAmountFairValueDisclosureMember2022-12-310000858470us-gaap:EstimateOfFairValueFairValueDisclosureMember2022-12-310000858470us-gaap:CarryingReportedAmountFairValueDisclosureMember2021-12-310000858470us-gaap:EstimateOfFairValueFairValueDisclosureMember2021-12-310000858470cog:TransportationAgreementObligationMember2022-12-310000858470cog:MinimumVolumeCommitmentsMember2022-12-310000858470cog:MinimumVolumeDeliveryCommitmentsMember2022-12-310000858470cog:MinimumVolumeDeliveryCommitmentsMemberus-gaap:OtherNoncurrentLiabilitiesMember2022-12-310000858470cog:MinimumVolumeWaterDeliveryCommitmentsMember2022-12-310000858470us-gaap:OtherNoncurrentLiabilitiesMembercog:MinimumVolumeWaterDeliveryCommitmentsMember2022-12-310000858470srt:MinimumMember2022-12-310000858470srt:MaximumMember2022-12-310000858470cog:DrillingRigsFracturingAndOtherEquipmentMembersrt:MinimumMember2022-01-012022-12-310000858470cog:DrillingRigsFracturingAndOtherEquipmentMembersrt:MaximumMember2022-01-012022-12-310000858470cog:OfficeOfAttorneyGeneralOfTheCommonwealthOfPennsylvaniaMember2022-11-292022-11-290000858470cog:OfficeOfAttorneyGeneralOfTheCommonwealthOfPennsylvaniaMembercog:CharityDonationMember2022-11-292022-11-290000858470cog:PennsylvaniaDepartmentOfEnvironmentalProtectionMember2022-11-292022-11-290000858470srt:MaximumMember2023-01-012022-12-310000858470us-gaap:DomesticCountryMember2022-12-310000858470us-gaap:StateAndLocalJurisdictionMember2022-12-310000858470us-gaap:CapitalLossCarryforwardMember2022-12-310000858470cog:OilRecoveryCreditsCarryforwardMember2022-12-310000858470us-gaap:StateAndLocalJurisdictionMemberus-gaap:CapitalLossCarryforwardMember2022-12-310000858470us-gaap:ResearchMember2022-12-310000858470cog:CimarexMemberus-gaap:ResearchMember2022-12-31cog:Retiree0000858470cog:SavingsInvestmentPlanMember2022-01-012022-12-310000858470cog:A401kPlanMember2022-01-012022-12-310000858470cog:A401kPlanMember2021-01-012021-12-310000858470cog:A401kPlanMember2020-01-012020-12-310000858470cog:DeferredCompensationPlanMember2022-01-012022-12-310000858470cog:DeferredCompensationPlanMember2021-01-012021-12-310000858470cog:DeferredCompensationPlanMember2022-12-310000858470cog:DeferredCompensationPlanMember2021-12-310000858470srt:ExecutiveOfficerMember2021-10-012021-10-010000858470cog:DeferredCompensationPlanMember2020-01-012020-12-310000858470cog:CimarexStockholdersMember2021-10-010000858470us-gaap:RestrictedStockMembercog:CimarexStockholdersMember2021-10-0100008584702021-09-2800008584702021-09-2900008584702022-01-012022-03-3100008584702022-04-012022-06-3000008584702022-07-012022-09-3000008584702022-10-012022-12-3100008584702021-01-012021-03-3100008584702021-04-012021-06-3000008584702021-07-012021-09-3000008584702021-10-012021-12-3100008584702020-01-012020-03-3100008584702020-04-012020-06-3000008584702020-07-012020-09-3000008584702020-10-012020-12-3100008584702021-10-012021-10-310000858470us-gaap:SubsequentEventMember2023-02-012023-02-270000858470us-gaap:SubsequentEventMember2023-02-2700008584702022-02-280000858470us-gaap:RedeemablePreferredStockMember2021-10-3100008584702021-10-010000858470us-gaap:RedeemablePreferredStockMember2022-05-012022-05-310000858470us-gaap:CommonStockMember2022-05-310000858470us-gaap:RedeemablePreferredStockMember2022-05-310000858470cog:StockIncentivePlan2014Member2014-05-010000858470us-gaap:EmployeeStockOptionMembercog:StockIncentivePlan2014Membersrt:MaximumMember2014-05-010000858470cog:StockIncentivePlan2014Membersrt:ScenarioForecastMember2024-05-012024-05-010000858470cog:StockIncentivePlan2014Member2022-12-310000858470cog:CimarexEnergyCoAmendedAndRestated2019EquityIncentivePlanMember2022-12-310000858470us-gaap:RestrictedStockUnitsRSUMember2022-01-012022-12-310000858470us-gaap:RestrictedStockUnitsRSUMember2021-01-012021-12-310000858470us-gaap:RestrictedStockUnitsRSUMember2020-01-012020-12-310000858470us-gaap:RestrictedStockMember2022-01-012022-12-310000858470us-gaap:RestrictedStockMember2021-01-012021-12-310000858470us-gaap:RestrictedStockMember2020-01-012020-12-310000858470us-gaap:PerformanceSharesMember2022-01-012022-12-310000858470us-gaap:PerformanceSharesMember2021-01-012021-12-310000858470us-gaap:PerformanceSharesMember2020-01-012020-12-310000858470cog:DeferredPerformanceSharesMember2022-01-012022-12-310000858470cog:DeferredPerformanceSharesMember2021-01-012021-12-310000858470cog:DeferredPerformanceSharesMember2020-01-012020-12-310000858470cog:DividendEquivalentsMember2022-01-012022-12-310000858470cog:DividendEquivalentsMember2021-01-012021-12-310000858470cog:DividendEquivalentsMember2020-01-012020-12-310000858470us-gaap:PerformanceSharesMember2021-10-012021-12-310000858470us-gaap:PerformanceSharesMember2022-07-012022-09-300000858470us-gaap:RestrictedStockUnitsRSUMemberus-gaap:ShareBasedPaymentArrangementEmployeeMember2022-01-012022-12-310000858470us-gaap:RestrictedStockUnitsRSUMembersrt:MinimumMemberus-gaap:ShareBasedCompensationAwardTrancheOneMemberus-gaap:ShareBasedPaymentArrangementEmployeeMember2022-01-012022-12-310000858470us-gaap:RestrictedStockUnitsRSUMemberus-gaap:ShareBasedCompensationAwardTrancheOneMembersrt:MaximumMemberus-gaap:ShareBasedPaymentArrangementEmployeeMember2022-01-012022-12-310000858470us-gaap:RestrictedStockUnitsRSUMembersrt:MinimumMemberus-gaap:ShareBasedPaymentArrangementEmployeeMember2022-01-012022-12-310000858470us-gaap:RestrictedStockUnitsRSUMembersrt:MaximumMemberus-gaap:ShareBasedPaymentArrangementEmployeeMember2022-01-012022-12-310000858470us-gaap:RestrictedStockUnitsRSUMemberus-gaap:ShareBasedPaymentArrangementEmployeeMember2021-12-310000858470us-gaap:RestrictedStockUnitsRSUMemberus-gaap:ShareBasedPaymentArrangementEmployeeMember2022-12-310000858470us-gaap:RestrictedStockUnitsRSUMemberus-gaap:ShareBasedPaymentArrangementEmployeeMember2021-01-012021-12-310000858470us-gaap:RestrictedStockUnitsRSUMemberus-gaap:ShareBasedPaymentArrangementEmployeeMember2020-01-012020-12-310000858470us-gaap:ShareBasedPaymentArrangementNonemployeeMemberus-gaap:RestrictedStockUnitsRSUMember2021-12-310000858470us-gaap:ShareBasedPaymentArrangementNonemployeeMemberus-gaap:RestrictedStockUnitsRSUMember2022-01-012022-12-310000858470us-gaap:ShareBasedPaymentArrangementNonemployeeMemberus-gaap:RestrictedStockUnitsRSUMember2022-12-310000858470us-gaap:ShareBasedPaymentArrangementNonemployeeMemberus-gaap:RestrictedStockUnitsRSUMember2021-01-012021-12-310000858470us-gaap:ShareBasedPaymentArrangementNonemployeeMemberus-gaap:RestrictedStockUnitsRSUMember2020-01-012020-12-310000858470us-gaap:ShareBasedCompensationAwardTrancheOneMemberus-gaap:RestrictedStockMember2022-01-012022-12-310000858470srt:MinimumMemberus-gaap:RestrictedStockMember2022-01-012022-12-310000858470us-gaap:RestrictedStockMembersrt:MaximumMember2022-01-012022-12-310000858470us-gaap:RestrictedStockMember2021-12-310000858470us-gaap:RestrictedStockMember2022-12-310000858470us-gaap:RestrictedStockMember2021-10-012021-10-010000858470cog:InternalMetricsPerformanceShareAwardsMember2022-01-012022-12-310000858470cog:EmployeePerformanceSharesMember2022-01-012022-12-310000858470us-gaap:ShareBasedCompensationAwardTrancheThreeMembercog:EmployeePerformanceSharesMember2022-01-012022-12-310000858470cog:EmployeePerformanceSharesMember2021-12-310000858470cog:EmployeePerformanceSharesMember2022-12-310000858470cog:EmployeePerformanceSharesMember2022-07-012022-07-310000858470cog:MarketBasedPerformanceShareAwardsMember2022-01-012022-12-310000858470cog:TSRPerformanceSharesMember2022-01-012022-12-310000858470cog:TSRPerformanceSharesMember2021-12-310000858470cog:TSRPerformanceSharesMember2022-12-310000858470cog:TSRPerformanceSharesMemberus-gaap:LiabilityMember2022-12-310000858470cog:TSRPerformanceSharesMemberus-gaap:LiabilityMember2021-12-310000858470cog:TSRPerformanceSharesMember2021-01-012021-12-310000858470cog:TSRPerformanceSharesMember2020-01-012020-12-310000858470cog:TSRPerformanceSharesMemberus-gaap:StockholdersEquityTotalMember2022-12-310000858470cog:TSRPerformanceSharesMemberus-gaap:StockholdersEquityTotalMember2021-12-310000858470cog:TSRPerformanceSharesMemberus-gaap:StockholdersEquityTotalMember2020-12-310000858470cog:TSRPerformanceSharesMemberus-gaap:StockholdersEquityTotalMember2022-01-012022-12-310000858470cog:TSRPerformanceSharesMemberus-gaap:StockholdersEquityTotalMember2021-01-012021-12-310000858470cog:TSRPerformanceSharesMemberus-gaap:StockholdersEquityTotalMember2020-01-012020-12-310000858470cog:TSRPerformanceSharesMemberus-gaap:LiabilityMembersrt:MinimumMember2020-12-310000858470cog:TSRPerformanceSharesMemberus-gaap:LiabilityMembersrt:MaximumMember2020-12-310000858470cog:TSRPerformanceSharesMemberus-gaap:LiabilityMember2022-01-012022-12-310000858470cog:TSRPerformanceSharesMemberus-gaap:LiabilityMember2021-01-012021-12-310000858470cog:TSRPerformanceSharesMemberus-gaap:LiabilityMembersrt:MinimumMember2020-01-012020-12-310000858470cog:TSRPerformanceSharesMemberus-gaap:LiabilityMembersrt:MaximumMember2020-01-012020-12-310000858470cog:TSRPerformanceSharesMemberus-gaap:LiabilityMember2020-01-012020-12-310000858470us-gaap:RestrictedStockUnitsRSUMember2022-12-310000858470us-gaap:PerformanceSharesMember2022-12-3100008584702021-10-012021-10-010000858470srt:MinimumMember2021-10-012021-10-010000858470srt:MaximumMember2021-10-012021-10-010000858470us-gaap:DeferredCompensationShareBasedPaymentsMember2022-12-310000858470us-gaap:ShareBasedCompensationAwardTrancheThreeMembercog:EmployeePerformanceSharesMember2021-01-012021-12-310000858470us-gaap:ShareBasedCompensationAwardTrancheThreeMembercog:EmployeePerformanceSharesMember2020-01-012020-12-310000858470cog:TreasuryStockMethodMember2022-01-012022-12-310000858470cog:TreasuryStockMethodMember2021-01-012021-12-310000858470cog:TreasuryStockMethodMember2020-01-012020-12-31

UNITED STATES

SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION

WASHINGTON, D. C. 20549

FORM 10-K

ANNUAL REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d)

OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934

For the fiscal year ended December 31, 2022

Commission file number 1-10447

COTERRA ENERGY INC.

(Exact name of registrant as specified in its charter)

| | | | | | | | |

| Delaware | | 04-3072771 |

(State or other jurisdiction of

incorporation or organization) | | (I.R.S. Employer

Identification Number) |

Three Memorial City Plaza,

840 Gessner Road, Suite 1400, Houston, Texas 77024

(Address of principal executive offices including ZIP code)

(281) 589-4600

(Registrant’s telephone number, including area code)

Securities registered pursuant to Section 12(b) of the Act:

| | | | | | | | |

| Title of each class | Trading Symbol(s) | Name of each exchange on which registered |

| Common Stock, par value $0.10 per share | CTRA | New York Stock Exchange |

Securities registered pursuant to Section 12(g) of the Act: None

Indicate by check mark if the registrant is a well-known seasoned issuer, as defined in Rule 405 of the Securities Act. Yes ☒ No ☐

Indicate by check mark if the registrant is not required to file reports pursuant to Section 13 or Section 15(d) of the Act. Yes ☐ No ☒

Indicate by check mark whether the registrant (1) has filed all reports required to be filed by Section 13 or 15(d) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 during the preceding 12 months (or for such shorter period that the registrant was required to file such reports), and (2) has been subject to such filing requirements for the past 90 days. Yes ☒ No ☐

Indicate by check mark whether the registrant has submitted electronically every Interactive Data File required to be submitted pursuant to Rule 405 of Regulation S-T (§ 232.405 of this chapter) during the preceding 12 months (or for such shorter period that the registrant was required to submit such files). Yes ☒ No ☐

Indicate by check mark whether the registrant is a large accelerated filer, an accelerated filer, a non-accelerated filer, a smaller reporting company, or an emerging growth company. See the definitions of “large accelerated filer,” “accelerated filer,” “smaller reporting company,” and “emerging growth company” in Rule 12b-2 of the Exchange Act.

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| Large accelerated filer | ☒ | Accelerated filer | ☐ | | Non-accelerated filer

| ☐ | Smaller reporting company | ☐ | Emerging growth company | ☐ |

If an emerging growth company, indicate by check mark if the registrant has elected not to use the extended transition period for complying with any new or revised financial accounting standards provided pursuant to Section 13(a) of the Exchange Act. ☐ Indicate by check mark whether the registrant has filed a report on and attestation to its management’s assessment of the effectiveness of its internal control over financial reporting under Section 404(b) of the Sarbanes-Oxley Act (15 U.S.C. 7262(b)) by the registered public accounting firm that prepared or issued its audit report. ☒

If securities are registered pursuant to Section 12(b) of the Act, indicate by check mark whether the financial statements of the registrant included in the filing reflect the correction of an error to previously issued financial statements. ☐

Indicate by check mark whether any of those error corrections are restatements that required a recovery analysis of incentive-based compensation received by any of the registrant’s executive officers during the relevant recovery period pursuant to §240.10D-1(b). ☐

Indicate by check mark whether the registrant is a shell company (as defined in Rule 12b-2 of the Act). Yes ☐ No ☒

The aggregate market value of Common Stock, par value $0.10 per share (“Common Stock”), held by non-affiliates as of the last business day of registrant’s most recently completed second fiscal quarter (based upon the closing sales price on the New York Stock Exchange on June 30, 2022) was approximately $20.2 billion.

As of February 24, 2023, there were 768,258,911 shares of Common Stock outstanding.

DOCUMENTS INCORPORATED BY REFERENCE

Portions of the Proxy Statement for the Annual Meeting of Stockholders to be held May 4, 2023 are incorporated by reference into Part III of this report.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

FORWARD-LOOKING INFORMATION

This report includes forward-looking statements within the meaning of federal securities laws. All statements, other than statements of historical fact, included in this report are forward-looking statements. Such forward-looking statements include, but are not limited to, statements regarding future financial and operating performance and results, the anticipated effects of, and certain other matters related to, the merger involving Cimarex Energy Co. (“Cimarex”), strategic pursuits and goals, market prices, future hedging and risk management activities, and other statements that are not historical facts contained in this report. The words “expect,” “project,” “estimate,” “believe,” “anticipate,” “intend,” “budget,” “plan,” “forecast,” “target,” “predict,” “potential,” “possible,” “may,” “should,” “could,” “would,” “will,” “strategy,” “outlook” and similar expressions are also intended to identify forward-looking statements. We can provide no assurance that the forward-looking statements contained in this report will occur as expected, and actual results may differ materially from those included in this report. Forward-looking statements are based on current expectations and assumptions that involve a number of risks and uncertainties that could cause actual results to differ materially from those included in this report. These risks and uncertainties include, without limitation, the impact of public health crises, including pandemics (such as the coronavirus (“COVID-19”) pandemic) and epidemics and any related company or governmental policies or actions, the risk that our and Cimarex’s businesses will not be integrated successfully, the risk that the cost savings and any other synergies from the merger involving Cimarex may not be fully realized or may take longer to realize than expected, the availability of cash on hand and other sources of liquidity to fund our capital expenditures, actions by, or disputes among or between, members of OPEC+, market factors, market prices (including geographic basis differentials) of oil and natural gas, impacts of inflation, labor shortages and economic disruption, including as a result of pandemics and geopolitical disruptions such as the war in Ukraine, results of future drilling and marketing activities, future production and costs, legislative and regulatory initiatives, electronic, cyber or physical security breaches and other factors detailed herein and in our other Securities and Exchange Commission (“SEC”) filings. Additional important risks, uncertainties and other factors are described in “Risk Factors” in Part I. Item 1A of this report. Forward-looking statements are based on the estimates and opinions of management at the time the statements are made. Except to the extent required by applicable law, we undertake no obligation to update or revise any forward-looking statement, whether as a result of new information, future events or otherwise. You are cautioned not to place undue reliance on these forward-looking statements, which speak only as of the date hereof.

Investors should note that we announce material financial information in SEC filings, press releases and public conference calls. Based on guidance from the SEC, we may use the Investors section of our website (www.coterra.com) to communicate with investors. It is possible that the financial and other information posted there could be deemed to be material information. The information on our website is not part of, and is not incorporated into, this report.

GLOSSARY OF CERTAIN OIL AND GAS TERMS

The following are abbreviations and definitions of certain terms commonly used in the oil and gas industry and included within this Annual Report on Form 10-K:

Bbl. One stock tank barrel, or 42 U.S. gallons liquid volume, used in reference to oil or other liquid hydrocarbons.

Bcf. One billion cubic feet of natural gas.

Boe. Barrels of oil equivalent.

Btu. British thermal units, a measure of heating value.

DD&A. Depletion, depreciation and amortization.

EHS. Environmental, health and safety.

ESG. Environmental, social and governance.

GAAP. Accounting principles generally accepted in the U.S.

GHG. Greenhouse gases.

Hydraulic fracturing. A technology involving the injection of fluids typically including small amounts of several chemical additives as well as sand into a well under high pressure in order to create fractures in the formation that allow oil or natural gas to flow more freely to the wellbore.

MBbl. One thousand barrels of oil or other liquid hydrocarbons.

MBblpd. One thousand barrels of oil or other liquid hydrocarbons per day.

MBoe. One thousand barrels of oil equivalent.

MBoepd. One thousand barrels of oil equivalent per day.

Mcf. One thousand cubic feet of natural gas.

MMBbl. One million barrels of oil or other liquid hydrocarbons.

MMBoe. One million barrels of oil equivalent.

MMBtu. One million British thermal units.

MMcf. One million cubic feet of natural gas.

MMcfpd. One million cubic feet of natural gas per day.

Net Acres or Net Wells. The sum of the fractional working interest owned in gross acres or gross wells expressed in whole numbers and fractions of whole numbers.

Net Production. Gross production multiplied by net revenue interest.

NGLs. Natural gas liquids.

NYMEX. New York Mercantile Exchange.

NYSE. New York Stock Exchange.

OPEC+. Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries and other oil exporting nations.

Proved developed reserves. Developed reserves are reserves that can be expected to be recovered: (1) through existing wells with existing equipment and operating methods or in which the cost of the required equipment is relatively minor compared to the cost of a new well; and (2) through installed extraction equipment and infrastructure operational at the time of the reserves estimate if the extraction is by means not involving a well.

Proved reserves. Proved reserves are those quantities, which, by analysis of geoscience and engineering data, can be estimated with reasonable certainty to be economically producible from a given date forward, from known reservoirs, and under existing economic conditions and operating methods prior to the time at which contracts providing the right to operate expire, unless evidence indicates that renewal is reasonably certain, regardless of whether deterministic or probabilistic methods are used for the estimation. The project to extract hydrocarbons must have commenced or the operator must be reasonably certain that it will commence the project within a reasonable time.

Existing economic conditions include prices and costs at which economic producibility from a reservoir is to be determined. The price shall be the average price during the 12-month period prior to the ending date of the period covered by the report, determined as an unweighted arithmetic average of the first-day-of-the-month price for each month within such period, unless prices are defined by contractual arrangements, excluding escalations based on future conditions.

Proved undeveloped reserves. Undeveloped reserves are reserves that are expected to be recovered from new wells on undrilled acreage, or from existing wells where a relatively major expenditure is required. Reserves on undrilled acreage are limited to those directly offsetting development spacing areas that are reasonably certain of production when drilled, unless evidence exists that establishes reasonable certainty of economic producibility at greater distances. Undrilled locations can be classified as having undeveloped reserves only if a development plan has been adopted indicating that they are scheduled to be drilled within five years, unless the specific circumstances justify a longer time. Under no circumstances shall estimates for undeveloped reserves be attributable to any acreage for which an application of fluid injection or other improved recovery technique is contemplated, unless such techniques have been proved effective by actual projects in the same reservoir or an analogous reservoir, or by other evidence using reliable technology establishing reasonable certainty.

PUD. Proved undeveloped.

SEC. Securities and Exchange Commission.

Tcf. One trillion cubic feet of natural gas.

U.S. United States.

Waha. Waha West Texas Natural Gas Index price as quoted in Platt’s Inside FERC.

WTI. West Texas Intermediate, a light sweet blend of oil produced from fields in western Texas and is a grade of oil used as a benchmark in oil pricing.

WTI Midland. WTI Midland Index price as quoted by Argus Americas Crude.

Energy equivalent is determined using the ratio of one barrel of crude oil, condensate or NGL to six Mcf of natural gas.

PART I

ITEMS 1 and 2. BUSINESS AND PROPERTIES

Coterra Energy Inc. (“Coterra,” “our,” “we” and “us”) is an independent oil and gas company engaged in the development, exploration and production of oil, natural gas and NGLs. Our assets are concentrated in areas with known hydrocarbon resources, which are conducive to multi-well, repeatable development programs. We operate in one segment, oil and natural gas development, exploration and production, in the continental U.S.

Our headquarters is located in Houston, Texas. We also maintain regional offices in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, Midland, Texas, and Tulsa, Oklahoma, as well as field offices near our operations.

On October 1, 2021, we completed a merger transaction (the “Merger”) with Cimarex. Cimarex is an oil and gas exploration and production company with operations in Texas, New Mexico and Oklahoma. Under the terms of the merger agreement relating to the Merger (the “Merger Agreement”), and subject to certain exceptions specified in the Merger Agreement, each eligible share of Cimarex common stock was converted into the right to receive 4.0146 shares of our common stock at closing. As a result of the completion of the Merger, we issued approximately 408.2 million shares of common stock to Cimarex stockholders (excluding shares that were awarded in replacement of certain previously outstanding Cimarex restricted share awards). Additionally, on October 1, 2021, we changed our name to Coterra Energy Inc.

Operational information set forth in this Annual Report on Form 10-K does not include the activity of Cimarex for periods prior to the completion of the Merger.

STRATEGY

Coterra is a premier U.S.-focused exploration and production company. We embrace innovation, technology and data, as we work to create value for our investors and the communities where we operate. We believe the following strategic priorities will help drive value creation and long-term success.

Generate Sustainable Returns. Our premier assets across multiple basins provide commodity diversification and strong cash flow generation through the commodity price cycles that, combined with our disciplined capital investment, give us the confidence in our ability to provide returns to our stockholders that we believe to be sustainable. Demonstrating our confidence in our business model, we increased our annual base dividend on our common stock to $0.50 per share following the consummation of the Merger, followed by an increase in February 2022 to $0.60 per share and an additional increase in February 2023 to $0.80 per share. From October 1, 2021 through our recent February 2023 dividend announcement, we will have returned approximately $3.2 billion to stockholders through our base, variable and special dividends. Furthermore, consistent with our returns-focused strategy, in February 2022, our Board of Directors approved a $1.25 billion share repurchase program, which was used to repurchase 48 million shares of our common stock, and was fully utilized by December 31, 2022. In February 2023, our Board of Directors approved a new share repurchase program which authorizes the purchase of up to $2.0 billion of our common stock. During 2022, we returned $4.06 per share to stockholders via dividend payments and share repurchases. Coterra remains committed to returning 50 percent or more of our free cash flow to our stockholders through our base dividend, share repurchase program, and/or a variable dividend.

Disciplined Capital Allocation Across Top-Tier Position. We believe our asset portfolio offers scale, capital optionality and low break-even investment options. We anticipate our drilling inventory will be developed over the coming decades at the current run-rate. We are committed to maintaining a disciplined capital investment strategy and using technology and innovation to maximize capital efficiency and operational execution. We believe that having three operating areas of scale, the Permian Basin, Marcellus Shale and Anadarko Basin, offers diversity of geography, commodity and revenue streams to allocate our capital, which should support strong and stable cash flow generation through commodity price cycles. During 2022, we invested 31 percent of our cash flow from operations in our drilling program and in 2023 expect to invest approximately 50 percent of our estimated cash flow from operations, based on current strip prices.

Maintain Financial Strength. We believe that maintaining an industry-leading balance sheet with significant financial flexibility is imperative in a cyclical industry exposed to commodity price volatility. We believe our asset base, revenue diversity, low-cost structure and strong balance sheet provide us the flexibility we need to thrive across various commodity price environments. During 2022, we retired $874 million of outstanding debt. With no significant debt maturities until 2024, a year-end 2022 cash balance of $673 million and $1.5 billion of unused commitments under our revolving credit facility, we believe we are well positioned to maintain our balance sheet strength.

Focus on Safe, Responsible and Sustainable Operations. We believe responsible development of oil and natural gas resources provides opportunity for a bright future, one built through technology and innovation that offers prosperity for

communities around the world. Our operational focus is based on making our operations more environmentally and socially sustainable by actively implementing technology across our operations from design phase to equipment improvements to limit and reduce our methane emissions and flaring activity. Our safety programs are built on a foundation that emphasizes personal safety and includes a Stop Work Authority program that empowers employees and contractors to stop work if they discover a dangerous condition or other serious EHS hazard. In addition, we focus on practical and sustainable environmental initiatives that promote efficient use of water and help to protect water quality, eliminate or mitigate releases, and minimize land surface impact. We are committed to being responsible stewards of our resources and implementing sustainable practices under the guidance of our management team and our diverse and experienced Board of Directors. We have published our 2022 Sustainability Report, which includes more information related to our sustainability practices, on our website at www.coterra.com. The information on our website is not part of, and is not incorporated into, this report on Form 10-K or any other report we may file with or furnish to the SEC (and is not deemed filed herewith), whether before or after the date of this report on Form 10-K and irrespective of any general incorporation language therein.

2023 OUTLOOK

Our 2023 capital program is expected to be approximately $2.0 billion to $2.2 billion. We expect to turn-in-line 150 to 175 total net wells in 2023 across our three operating regions. Approximately 49 percent of our drilling and completion capital will be invested in the Permian Basin, 44 percent in the Marcellus Shale and the balance in the Anadarko Basin.

DESCRIPTION OF PROPERTIES

Our operations are primarily concentrated in three operating areas—the Permian Basin in west Texas and southern New Mexico, the Marcellus Shale in northeast Pennsylvania and the Anadarko Basin in the Mid-Continent region in Oklahoma.

Permian Basin

Our Permian Basin properties are principally located in the western half of the Permian Basin known as the Delaware Basin where we currently hold approximately 307,000 net acres in the play. Our development activities are primarily focused on the Wolfcamp Shale and the Bone Spring formation in Culberson and Reeves Counties in Texas and Lea and Eddy Counties in New Mexico. Our 2022 net production in the Permian Basin was 211 MBoepd, representing 33 percent of our total equivalent production for the year. As of December 31, 2022, we had a total of 1,056.3 net wells in the Permian Basin, of which approximately 88 percent are operated by us.

During 2022, we invested $791 million in the Permian Basin, where we exited 2022 with six drilling rigs operating in the play and plan to exit 2023 with six rigs operating.

Marcellus Shale

Our Marcellus Shale properties are principally located in Susquehanna County, Pennsylvania, where we currently hold approximately 183,000 net acres in the dry gas window in the Marcellus Shale. Our 2022 net production in the Marcellus was 367 MBoepd, representing 58 percent of our total equivalent production for the year. As of December 31, 2022, we had a total of 1,024.2 net wells in the Marcellus Shale, of which approximately 99 percent are operated by us.

During 2022, we invested $813 million in the Marcellus Shale, where we exited 2022 with two drilling rigs operating in the play and plan to exit 2023 with two rigs operating.

Anadarko Basin

Our Anadarko Basin properties are principally located in Oklahoma where we currently hold approximately 182,000 net acres in the play. Our development activities are primarily focused on the Woodford Shale and the Meramec formation, both in Oklahoma. Our 2022 net production in the Anadarko Basin was 55 MBoepd, representing nine percent of our total equivalent production for the year. As of December 31, 2022, we had a total of 511.4 net wells in the Anadarko Basin, of which approximately 60 percent are operated by us.

During 2022, we invested $121 million in the Anadarko Basin. At the end of 2022, we had one rig operating in the play for a multi-well program expected to run through mid-2023.

Other Properties

Ancillary to our exploration, development and production operations, we operate a number of natural gas gathering and saltwater gathering and disposal systems. The majority of our gathering infrastructure is located in Texas and directly supports our Permian Basin operations. Our gathering systems enable us to connect new wells quickly and to transport natural gas from

the wellhead directly to interstate pipelines and natural gas processing facilities and to transport water produced along with oil and gas (“produced water”) for re-use in completions activities and to disposal facilities. Control of our gathering pipeline systems also enables us to transport natural gas produced by third parties. In addition, we can engage in development drilling without relying on third parties to transport our natural gas or produced water and incur only the incremental costs of pipeline and compressor additions to our system.

MARKETING

Substantially all of our oil and natural gas production is sold at market sensitive prices under both long-term and short-term sales contracts. We sell oil, natural gas and NGLs to a broad portfolio of customers, including industrial customers, local distribution companies, oil and gas marketers, major energy companies, pipeline companies and power generation facilities.

Demand for natural gas has historically been seasonal, with peak demand and typically higher prices occurring during the winter months.

We also incur transportation and gathering expenses to move our oil and natural gas production from the wellhead to our principal markets in the U.S. The majority of our Marcellus Shale and Anadarko Basin natural gas production is gathered on third-party gathering systems, while the majority of our Permian Basin natural gas production is gathered on company-owned and operated gathering systems. Most of our natural gas is transported on interstate pipelines where we have long-term contractual capacity arrangements or use purchaser-owned capacity under both long-term and short-term sales contracts.

To date, we have not experienced significant difficulty in transporting or marketing our production as it becomes available; however, there is no assurance that we will always be able to transport and market all of our production.

Delivery Commitments

We have entered into various firm sales contracts to deliver and sell natural gas. We believe we will have sufficient production quantities to meet substantially all of our commitments, but may be required to purchase natural gas from third parties to satisfy shortfalls should they occur.

A summary of our firm sales commitments as of December 31, 2022 are set forth in the table below: | | | | | | | | |

| | Natural Gas (in Bcf) |

| 2023 | | 644 | |

| 2024 | | 601 | |

| 2025 | | 577 | |

| 2026 | | 572 | |

| 2027 | | 549 | |

| | |

We utilize a part of our firm transportation capacity to deliver natural gas under the majority of these firm sales contracts and have entered into numerous agreements for transportation of our production. Some of these contracts have volumetric requirements which could require monetary shortfall penalties if our production is inadequate to meet the terms. However, we do not believe we will have any financial commitment due based on our current proved reserves and production levels from which we can fulfill these obligations.

RISK MANAGEMENT

From time to time, we use derivative financial instruments to manage price risk associated with our oil and natural gas production. Although there are many different types of derivatives available, we generally utilize collar, swap and basis swap agreements designed to assist us in managing price risk. The collar arrangements are a combination of put and call options used to establish floor and ceiling prices for a fixed volume of production during a certain time period. They provide for payments to counterparties if the index price exceeds the ceiling and payments from the counterparties if the index price falls below the floor. The swap agreements call for payments to, or receipts from, counterparties based on whether the index price for the period is greater or less than the fixed price established for the particular period under the swap agreement.

During 2022, natural gas collars with floor prices ranging from $1.70 to $8.50 per MMBtu and ceiling prices ranging from $2.10 to $13.08 per MMBtu covered 245.8 Bcf, or 24 percent, of natural gas production at a weighted-average price of $4.94 per MMBtu. Natural gas swaps covered 14.9 Bcf, or one percent, of natural gas production at a weighted-average price of $2.26 per MMBtu.

During 2022, oil collars with floor prices ranging from $35.00 to $90.00 per Bbl and ceiling prices ranging from $45.15 to $145.25 per Bbl covered 9.7 MMBbls, or 31 percent, of oil production at a weighted-average price of $55.00 per Bbl. Oil basis swaps covered 8.7 MMBbls, or 27 percent, of oil production at a weighted-average price of $0.30 per Bbl. Oil roll differential swaps covered 2.7 MMBbls, or 9 percent, of oil production at a weighted-average price of $(0.02) per Bbl.

As of December 31, 2022, we had the following outstanding financial commodity derivatives:

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| | | | | | |

| | | 2023 | | | | |

| Natural Gas | | First Quarter | | Second Quarter | | Third Quarter | | Fourth Quarter | | | | |

| | | | | | | | | | | | |

| | | | | | | | | | | | |

| | | | | | | | | | | | |

| | | | | | | | | | | | |

| Waha gas collars | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| Volume (MMBtu) | | 8,100,000 | | | 8,190,000 | | | 8,280,000 | | | 8,280,000 | | | | | |

Weighted average floor ($/MMBtu) | | $ | 3.03 | | | $ | 3.03 | | | $ | 3.03 | | | $ | 3.03 | | | | | |

Weighted average ceiling ($/MMBtu) | | $ | 5.39 | | | $ | 5.39 | | | $ | 5.39 | | | $ | 5.39 | | | | | |

| | | | | | | | | | | | |

| NYMEX collars | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| Volume (MMBtu) | | 54,000,000 | | | 31,850,000 | | | 32,200,000 | | | 29,150,000 | | | | | |

Weighted average floor ($/MMBtu) | | $ | 5.12 | | | $ | 4.07 | | | $ | 4.07 | | | $ | 4.03 | | | | | |

Weighted average ceiling ($/MMBtu) | | $ | 9.34 | | | $ | 6.78 | | | $ | 6.78 | | | $ | 6.61 | | | | | |

| | | | | | | | | | | | |

| | | | | | | | | | | | |

| | | | | | | | | | | | |

| | | | | | | | | | | | |

| | | | | | | | | | | | |

| | | | | | | | | | | | |

| | | | | | | | | | | | |

| | | | | | | | | | | | |

| | | | | | | | | | | | |

| | | | | | | | | | | | |

| | | | | | | | | | | | |

| | | | | | | | | | | | |

| | | | | | | | | | | | |

| | | | | | | | | | | | |

| | | | | | | | | | | | |

| | | | | | | | | | | | |

| | | | | | | | | | | | |

| | | | | | | | | | | | |

| | | | | | | | | | | | |

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| | | | | | |

| | 2023 | | | | |

| Oil | | First Quarter | | Second Quarter | | | | | | | | |

| WTI oil collars | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| Volume (MBbl) | | 1,350 | | | 1,365 | | | | | | | | | |

| Weighted average floor ($/Bbl) | | $ | 70.00 | | | $ | 70.00 | | | | | | | | | |

| Weighted average ceiling ($/Bbl) | | $ | 116.03 | | | $ | 116.03 | | | | | | | | | |

| | | | | | | | | | | | |

| WTI Midland oil basis swaps | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| Volume (MBbl) | | 1,350 | | | 1,365 | | | | | | | | | |

| Weighted average differential ($/Bbl) | | $ | 0.63 | | | $ | 0.63 | | | | | | | | | |

| | | | | | | | | | | | |

| | | | | | | | | | | | |

| | | | | | | | | | | | |

| | | | | | | | | | | | |

| | | | | | | | | | | | |

| | | | | | | | | | | | |

| | | | | | | | | | | | |

| | | | | | | | | | | | |

| | | | | | | | | | | | |

| | | | | | | | | | | | |

| | | | | | | | | | | | |

| | | | | | | | | | | | |

| | | | | | | | | | | | |

A significant portion of our expected oil and natural gas production for 2023 and beyond is currently unhedged and directly exposed to the volatility in oil and natural gas prices, whether favorable or unfavorable. We will continue to evaluate the benefit of using derivatives in the future. Please read “Management’s Discussion and Analysis of Financial Condition and Results of Operations” and “Quantitative and Qualitative Disclosures about Market Risk” for further discussion related to our use of derivatives.

PROVED OIL AND GAS RESERVES

The following table presents our estimated proved reserves by commodity as of the dates indicated:

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| | December 31, |

| | 2022 | | 2021 | | 2020 |

| Oil (MBbl) | | | | | |

| Proved developed reserves | 168,649 | | | 153,010 | | | — | |

Proved undeveloped reserves | 71,107 | | | 36,419 | | | — | |

| 239,756 | | | 189,429 | | | — | |

| Natural Gas (Bcf) | | | | | |

| Proved developed reserves | 8,543 | | | 10,691 | | | 8,608 | |

| Proved undeveloped reserves | 2,630 | | | 4,204 | | | 5,064 | |

| 11,173 | | | 14,895 | | | 13,672 | |

| NGLs (MBbl) | | | | | |

| Proved developed reserves | 224,706 | | | 193,598 | | | — | |

| Proved undeveloped reserves | 72,059 | | | 27,017 | | | — | |

| 296,765 | | | 220,615,000 | | | — | |

| | | | | |

Oil equivalent (MBoe) | 2,398,666 | | | 2,892,582 | | | 2,278,636 | |

| | | | | |

| | | | | |

| | | | | |

At December 31, 2022, our Dimock field, which is located in the Marcellus Shale in Susquehanna County, Pennsylvania, contained approximately 62 percent of our total proved reserves.

For additional information regarding estimates of our net proved and proved undeveloped reserves, the qualifications of the preparers of our reserves estimates, the evaluation of such estimates by our independent petroleum consultants, our processes and controls with respect to our reserves estimates and other information about our reserves, including the risks inherent in our estimates of proved reserves, refer to the Supplemental Oil and Gas Information included in Item 8 and “Risk Factors—Business and Operational Risks—Our proved reserves are estimates. Any material inaccuracies in our reserves estimates or underlying assumptions could cause the quantities and net present value of our reserves to be overstated or understated” in Item 1A.

PRODUCTION, SALES PRICE AND PRODUCTION COSTS

The following table presents historical information about our total and average daily production volumes for oil, natural gas and NGLs; average oil, natural gas and NGL sales prices; and average production costs per equivalent:

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| | Year Ended December 31, |

| | 2022 | | 2021 (1) | | 2020 |

| Production Volumes | | | | | | |

| Oil (MBbl) | | 31,926 | | 8,150 | | — | |

| Natural gas (Bcf) | | 1,024 | | 911 | | 858 |

| NGL (MBbl) | | 28,697 | | 7,104 | | — | |

| Equivalents (MBoe) | | 231,342 | | 167,113 | | 142,954 |

| | | | | | |

| Average Daily Production Volumes | | | | | | |

| Oil (MBbl) | | 87 | | 89 | | — | |

| Natural gas (MMcf) | | 2,806 | | 2,492 | | 2,344 |

| NGL (MBbl) | | 79 | | 77 | | — | |

| Equivalents (MBoe) | | 634 | | | 660 | | 391 | |

| | | | | | |

| Average Sales Price | | | | | | |

| Excluding Derivative Settlements | | | | | | |

| Oil ($/Bbl) | | $ | 94.47 | | | $ | 75.61 | | | $ | — | |

| Natural gas ($/Mcf) | | $ | 5.34 | | | $ | 3.07 | | | $ | 1.64 | |

| NGL ($/Bbl) | | $ | 33.58 | | | $ | 34.18 | | | $ | — | |

| Including Derivative Settlements | | | | | | |

| Oil ($/Bbl) | | $ | 84.33 | | | $ | 60.35 | | | $ | — | |

| Natural gas ($/Mcf) | | $ | 4.91 | | | $ | 2.73 | | | $ | 1.68 | |

| NGL ($/Bbl) | | $ | 33.58 | | | $ | 34.18 | | | $ | — | |

| | | | | | |

| Average Production Costs ($/Boe) | | $ | 1.84 | | | $ | 0.77 | | | $ | 0.36 | |

_______________________________________________________________________________

(1)On October 1, 2021, we completed the Merger. The production information presented in this table includes Cimarex production for the period subsequent to that date.

The following table presents historical information about our total and average daily natural gas production volumes associated with our interests in the Dimock field in the Marcellus Shale, which contains 15 percent or more of our total proved reserves. There was no oil or NGL production associated with our interests in the Dimock field: | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| | Year Ended December 31, |

| | 2022 | | 2021 | | 2020 |

| Production Volumes | | | | | | |

| | | | | | |

| Natural gas (Bcf) | | 805 | | | 853 | | | 858 | |

| | | | | | |

| Equivalents (MBoe) | | 134,097 | | | 142,223 | | | 142,954 | |

| | | | | | |

| Average Daily Production Volumes | | | | | | |

| | | | | | |

| Natural gas (MMcf) | | 2,204 | | 2,338 | | | 2,344 | |

| | | | | | |

| Equivalents (MBoe) | | 367 | | 390 | | | 391 | |

ACREAGE

Our interest in both developed and undeveloped properties is primarily in the form of leasehold interests held under customary mineral leases. These leases provide us the right to develop oil and/or natural gas on the properties. Their primary terms generally range in length from approximately three to 10 years. These properties are held for longer periods if production is established.

The following table summarizes our gross and net developed and undeveloped leasehold acreage at December 31, 2022: | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| Acreage |

| | Developed | | Undeveloped | | Total |

| | Gross | | Net | | Gross | | Net | | Gross | | Net |

| Permian Basin | | | | | | | | | | | |

| New Mexico | 155,066 | | | 111,768 | | | 55,419 | | | 38,813 | | | 210,485 | | | 150,581 | |

| Texas | 204,971 | | | 136,845 | | | 23,999 | | | 19,354 | | | 228,970 | | | 156,199 | |

| 360,037 | | | 248,613 | | | 79,418 | | | 58,167 | | | 439,455 | | | 306,780 | |

| Marcellus Shale | | | | | | | | | | | |

| Pennsylvania | 165,999 | | | 165,180 | | | 19,334 | | | 17,790 | | | 185,333 | | | 182,970 | |

| | | | | | | | | | | |

| | | | | | | | | | | |

| Anadarko Basin | | | | | | | | | | | |

| | | | | | | | | | | |

| Oklahoma | 320,080 | | | 146,987 | | | 72,740 | | | 35,428 | | | 392,820 | | | 182,415 | |

| | | | | | | | | | | |

| | | | | | | | | | | |

| | | | | | | | | | | |

| Other | | | | | | | | | | | |

| Arizona | 17,207 | | | 17,207 | | | 2,097,841 | | | 2,097,841 | | | 2,115,048 | | | 2,115,048 | |

| California | — | | | — | | | 383,487 | | | 383,487 | | | 383,487 | | | 383,487 | |

| Colorado | 4,208 | | | 1,363 | | | 25,352 | | | 18,767 | | | 29,560 | | | 20,130 | |

| Kentucky | 122 | | | 92 | | | 22,436 | | | 19,222 | | | 22,558 | | | 19,314 | |

| Montana | 7,397 | | | 1,606 | | | 27,137 | | | 8,180 | | | 34,534 | | | 9,786 | |

| Nevada | 440 | | | 1 | | | 1,007,167 | | | 1,007,167 | | | 1,007,607 | | | 1,007,168 | |

| New Mexico | 10,655 | | | 2,436 | | | 1,640,195 | | | 1,634,459 | | | 1,650,850 | | | 1,636,895 | |

| Offshore Gulf of Mexico | 18,853 | | | 7,005 | | | 15,000 | | | 9,000 | | | 33,853 | | | 16,005 | |

| Pennsylvania | — | | | — | | | 111,422 | | | 62,884 | | | 111,422 | | | 62,884 | |

| Texas | 45,091 | | | 12,361 | | | 22,520 | | | 17,009 | | | 67,611 | | | 29,370 | |

| Utah | 4,803 | | | 1,442 | | | 61,320 | | | 57,177 | | | 66,123 | | | 58,619 | |

| West Virginia | — | | | — | | | 623,295 | | | 591,426 | | | 623,295 | | | 591,426 | |

| Wyoming | 22,071 | | | 2,345 | | | 79,522 | | | 23,751 | | | 101,593 | | | 26,096 | |

| Other | 8,435 | | | 1,714 | | | 57,097 | | | 30,275 | | | 65,532 | | | 31,989 | |

| 139,282 | | | 47,572 | | | 6,173,791 | | | 5,960,645 | | | 6,313,073 | | | 6,008,217 | |

| 985,398 | | | 608,352 | | | 6,345,283 | | | 6,072,030 | | | 7,330,681 | | | 6,680,382 | |

Total Net Undeveloped Acreage Expiration

The table below summarizes by year and operating area our undeveloped acreage expirations in the next three years. In most cases, the drilling of a commercial well will hold the acreage beyond the expiration.

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| | Acreage |

| | 2023 | | 2024 | | 2025 |

| | Gross | | Net | | Gross | | Net | | Gross | | Net |

| Permian Basin | | 960 | | | 960 | | | 3 | | | 3 | | | — | | | — | |

| Marcellus Shale | | 1,970 | | | 1,968 | | | 1,670 | | | 1,566 | | | 2,084 | | | 2,080 | |

| Anadarko Basin | | 4,097 | | | 934 | | | 700 | | | 134 | | | 520 | | | 125 | |

| Other | | 7,725 | | | 6,697 | | | 1,302 | | | 1,241 | | | — | | | — | |

| | 14,752 | | | 10,559 | | | 3,675 | | | 2,944 | | | 2,604 | | | 2,205 | |

| | | | | | | | | | | | |

| Percentage of total undeveloped acreage | | — | % | | — | % | | — | % | | — | % | | — | % | | — | % |

At December 31, 2022, we had no PUD reserves recorded on undeveloped acreage that were scheduled for development beyond the expiration dates of the undeveloped acreage or outside of our primary operating area.

WELL SUMMARY

The following table presents our ownership in productive oil and natural gas wells at December 31, 2022. This summary includes oil and natural gas wells in which we have a working interest:

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| | | Gross | | Net |

| Natural Gas | | 3,268 | | | 1,800.2 | |

| Oil | | 2,421 | | | 793.1 | |

Total(1) | | 5,689 | | | 2,593.3 | |

_______________________________________________________________________________

(1)Total percentage of gross and net operated wells is 49 percent and 87 percent, respectively.

DRILLING ACTIVITY

We drilled and completed wells or participated in the drilling and completion of wells as indicated in the table below. During the years presented below, we did not drill and complete any exploration wells. The information below should not be considered indicative of future performance, nor should a correlation be assumed between the number of productive wells drilled, quantities of reserves found or economic value.

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| | Year Ended December 31, |

| | 2022 | | 2021 | | 2020 |

| | Gross | | Net | | Gross | | Net | | Gross | | Net |

| Development Wells | | | | | | | | | | | |

| Productive | 284 | | | 173.9 | | | 114 | | | 99.9 | | | 74 | | | 64.3 | |

| Dry | 1 | | | 0.7 | | | — | | | — | | | — | | | — | |

| | | | | | | | | | | |

| | | | | | | | | | | |

| | | | | | | | | | | |

| Total | 285 | | | 174.6 | | | 114 | | | 99.9 | | | 74 | | | 64.3 | |

| | | | | | | | | | | |

| Acquired Wells | — | | | — | | | 7,266 | | | 1,715.3 | | | — | | | — | |

During the year ended December 31, 2022, we completed 58 gross wells (37.2 net) that were drilled in prior years.

The following table sets forth information about wells for which drilling was in progress or which were drilled but uncompleted at December 31, 2022, which are not included in the above table:

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| | Drilling In Progress | | Drilled But Uncompleted |

| | Gross | | Net | | Gross | | Net |

| Development wells | | 43 | | | 28.0 | | | 99 | | | 63.1 | |

| | | | | | | | |

| | | | | | | | |

OTHER BUSINESS MATTERS

Title to Properties

We believe that we have satisfactory title to all of our producing properties in accordance with generally accepted industry standards. Individual properties may be subject to burdens such as royalty, overriding royalty, carried, net profits, working and other outstanding interests customary in the industry. In addition, interests may be subject to obligations or duties under applicable laws or burdens such as production payments, ordinary course liens incidental to operating agreements and for current taxes or development obligations under oil and gas leases. As is customary in the industry in the case of undeveloped properties, we conduct preliminary investigations of record title at the time of lease acquisition. We conduct more complete investigations prior to the consummation of an acquisition of producing properties and before commencement of drilling operations on undeveloped properties.

Competition

The oil and gas industry is highly competitive, and we experience strong competition in our primary producing areas. We primarily compete with integrated, independent and other energy companies for the sale and transportation of our oil and natural gas production to pipelines, marketing companies and end users. Furthermore, the oil and gas industry competes with other energy industries that supply fuel and power to industrial, commercial and residential consumers. Many of these competitors have greater financial, technical and personnel resources than we have. The effect of these competitive factors cannot be predicted.

Price, contract terms, availability of rigs and related equipment and quality of service, including pipeline connection times and distribution efficiencies affect competition. We believe that our concentrated acreage positions and our access to both third-party and company-owned gathering and pipeline infrastructure in our primary operating areas, along with our expected activity level and the related services and equipment that we have secured for the upcoming years, enhance our competitive position compared to other producers who do not have similar systems or services in place.

Major Customers

During the year ended December 31, 2022, two customers accounted for approximately 13 percent and 11 percent of our total sales. During the year ended December 31, 2021, no customer accounted for more than 10 percent of our total sales. If any one of our major customers were to stop purchasing our production, we believe there are a number of other purchasers to whom we could sell our production. If multiple significant customers were to stop purchasing our production, we believe there could be some initial challenges, but we have sufficient alternative markets to handle any sales disruptions.

We regularly monitor the creditworthiness of our customers and may require parent company guarantees, letters of credit or prepayments when necessary. Historically, losses associated with uncollectible receivables have not been significant.

Regulation of Oil and Natural Gas Exploration and Production

Exploration and production operations are subject to various types of regulation at the federal, state and local levels. This regulation includes requiring permits to drill wells, maintaining bonding requirements to drill or operate wells, regulating the location of wells, the method of drilling and casing wells, the surface use and restoration of properties on which wells are drilled and the plugging and abandoning of wells. Our operations are also subject to various conservation laws and regulations. These include the regulation of the size of drilling and spacing units or proration units, the density of wells that may be drilled in a given field and the unitization or pooling of oil and gas properties. Some states allow the forced pooling or integration of tracts to facilitate exploration while other states rely on voluntary pooling of lands and leases. In addition, state conservation laws establish maximum rates of production from oil and natural gas wells, generally prohibiting the venting or flaring of natural gas and imposing certain requirements regarding the ratability of production. The effect of these regulations is to limit the amounts of oil and natural gas we can produce from our wells, and to limit the number of wells or the locations where we can drill. Because these statutes, rules and regulations undergo frequent review and often are amended, expanded and reinterpreted, we are unable to predict the future cost or impact of regulatory compliance. The regulatory burden on the oil and

gas industry increases our cost of doing business and, consequently, affects our profitability. We do not believe, however, we are affected differently by these regulations than others in the industry.

Regulation of Natural Gas Marketing, Gathering and Transportation

Federal legislation and regulatory controls have historically affected the price of the natural gas we produce and the manner in which our production is transported and marketed. Under the U.S. Natural Gas Act of 1938 (the “NGA”), the U.S. Natural Gas Policy Act of 1978 (the “NGPA”) and the regulations promulgated under those statutes, the U.S. Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (the “FERC”) regulates the interstate sale for resale of natural gas and the transportation of natural gas in interstate commerce, although facilities used in the production or gathering of natural gas in interstate commerce are generally exempted from FERC jurisdiction. Effective beginning in January 1993, the Natural Gas Wellhead Decontrol Act deregulated natural gas prices for all “first sales” of natural gas, which definition covers all sales of our own production. In addition, as part of the broad industry restructuring initiatives described below, the FERC granted to all producers such as us a “blanket certificate of public convenience and necessity” authorizing the sale of natural gas for resale without further FERC approvals. As a result of this policy, all of our produced natural gas is sold at market prices, subject to the terms of any private contracts that may be in effect. In addition, under the provisions of the Energy Policy Act of 2005 (“2005 Act”), the NGA was amended to prohibit any forms of market manipulation in connection with the purchase or sale of natural gas. Pursuant to the 2005 Act, the FERC established regulations intended to increase natural gas pricing transparency by, among other things, requiring market participants to report their gas sales transactions annually to the FERC. The 2005 Act also significantly increased the penalties for violations of the NGA and NGPA and the FERC’s regulations thereunder up to $1 million per day per violation. This maximum penalty authority established by statute has been and will continue to be adjusted periodically for inflation. The current maximum penalty is over $1 million per day per violation. In 2010, the FERC issued Penalty Guidelines for the determination of civil penalties and procedure under its enforcement program.

Under the NGPA, natural gas gathering facilities are expressly exempt from FERC jurisdiction. What constitutes “gathering” under the NGPA has evolved through FERC decisions and judicial review of such decisions. We believe that our gathering and production facilities meet the test for non-jurisdictional “gathering” systems under the NGPA and that our facilities are not subject to federal regulations. Although exempt from FERC oversight, our natural gas gathering systems and services may receive regulatory scrutiny by state and federal agencies regarding the safety and operating aspects of the transportation and storage activities of these facilities.

Our natural gas sales prices continue to be affected by intrastate and interstate gas transportation regulation because the cost of transporting the natural gas once sold to the consuming market is a factor in the prices we receive. Beginning with Order No. 436 in 1985 and continuing through Order No. 636 in 1992 and Order No. 637 in 2000, the FERC has adopted a series of rule makings that have significantly altered the transportation and marketing of natural gas. These changes were intended by the FERC to foster competition by, among other things, requiring interstate pipeline companies to separate their wholesale gas marketing business from their gas transportation business and by increasing the transparency of pricing for pipeline services. The FERC has also established regulations governing the relationship of pipelines with their marketing affiliates, which essentially require that designated employees function independently of each other and that certain information not be shared. The FERC has also implemented standards relating to the use of electronic data exchange by the pipelines to make transportation information available on a timely basis and to enable transactions to occur on a purely electronic basis.

In light of these statutory and regulatory changes, most pipelines have divested their natural gas sales functions to marketing affiliates, which operate separately from the transporter and in direct competition with all other merchants. Most pipelines have also implemented the large‑scale divestiture of their natural gas gathering facilities to affiliated or non-affiliated companies. Interstate pipelines are required to provide unbundled, open and nondiscriminatory transportation and transportation‑related services to producers, gas marketing companies, local distribution companies, industrial end users and other customers seeking such services. As a result of the FERC requiring natural gas pipeline companies to separate marketing and transportation services, sellers and buyers of natural gas have gained direct access to pipeline transportation services, and are better able to conduct business with a larger number of counterparties. We believe these changes generally have improved our access to markets while, at the same time, substantially increasing competition in the natural gas marketplace. We cannot predict what new or different regulations the FERC and other regulatory agencies may adopt, or what effect subsequent regulations may have on our activities. Similarly, we cannot predict what proposals, if any, that affect the oil and natural gas industry might actually be enacted by the U.S. Congress or the various state legislatures and what effect, if any, such proposals might have on us. Further, we cannot predict whether the recent trend toward federal deregulation of the natural gas industry will continue or what effect future policies will have on our sale of gas.

Federal Regulation of Swap Transactions

We use derivative financial instruments such as collar, swap and basis swap agreements to attempt to more effectively manage price risk due to the impact of changes in commodity prices on our operating results and cash flows. The Dodd‑Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act (“Dodd‑Frank Act”) enacted comprehensive financial reform, establishing federal oversight over and regulation of the over-the-counter derivatives market (which includes the sorts of financial instruments we use) and participants in the market. The Commodity Futures Trading Commission (the “CFTC”) has promulgated regulations to implement these reforms. While most of the regulations have been promulgated and are already in effect, the rulemaking and implementation process is still ongoing. We believe that our use of swaps to hedge against commodity exposure qualifies us as an end‑user, exempting us from the requirement to centrally clear our swaps. Nevertheless, the changes to other elements in the derivatives markets as a result of Dodd‑Frank and its current and ongoing implementation could significantly increase the cost of derivative contracts, limit the availability of derivatives to protect against risks that we encounter, reduce our ability to monetize or restructure our existing derivative contracts and increase our exposure to less creditworthy counterparties. If we reduce our use of swaps, our results of operations may become more volatile and our cash flows may be less predictable.

Federal Regulation of Petroleum

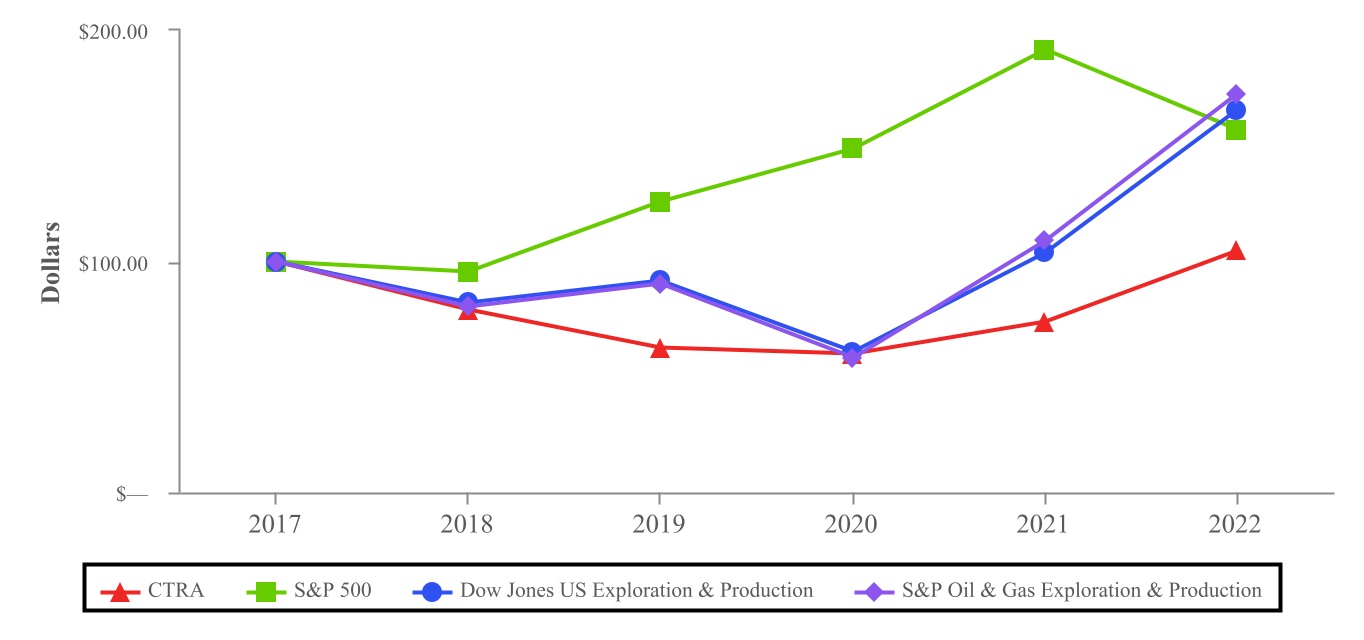

Sales of crude oil and NGLs are not regulated and are made at market prices. However, the price received from the sale of these products is affected by the cost of transporting the products to market. Much of that transportation is through interstate common carrier pipelines, which are regulated by the FERC under the Interstate Commerce Act (“ICA”). The FERC requires that pipelines regulated under the ICA file tariffs setting forth the rates and terms and conditions of service and that such service not be unduly discriminatory or preferential.