UNITED STATES

SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION

Washington, D.C. 20549

FORM

(Mark One)

ANNUAL REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 |

For the fiscal year ended

OR

TRANSITION REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 FOR THE TRANSITION PERIOD FROM TO |

Commission File Number

(Exact name of Registrant as specified in its Charter)

(State or other jurisdiction of incorporation or organization) |

(I.R.S. Employer Identification No.) |

(Address of principal executive offices) |

(Zip Code) |

Registrant’s telephone number, including area code: (

Securities registered pursuant to Section 12(b) of the Act:

Title of each class |

|

Trading Symbol(s) |

|

Name of each exchange on which registered |

|

|

The |

Securities registered pursuant to Section 12(g) of the Act: None

Indicate by check mark if the Registrant is a well-known seasoned issuer, as defined in Rule 405 of the Securities Act. YES ☐

Indicate by check mark if the Registrant is not required to file reports pursuant to Section 13 or 15(d) of the Act. YES ☐

Indicate by check mark whether the Registrant: (1) has filed all reports required to be filed by Section 13 or 15(d) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 during the preceding 12 months (or for such shorter period that the Registrant was required to file such reports), and (2) has been subject to such filing requirements for the past 90 days.

Indicate by check mark whether the Registrant has submitted electronically every Interactive Data File required to be submitted pursuant to Rule 405 of Regulation S-T (§232.405 of this chapter) during the preceding 12 months (or for such shorter period that the Registrant was required to submit such files).

Indicate by check mark whether the registrant is a large accelerated filer, an accelerated filer, a non-accelerated filer, smaller reporting company, or an emerging growth company. See the definitions of “large accelerated filer,” “accelerated filer,” “smaller reporting company,” and “emerging growth company” in Rule 12b-2 of the Exchange Act.

Large accelerated filer |

|

☐ |

|

Accelerated filer |

|

☐ |

|

☒ |

|

Smaller reporting company |

|

||

|

|

|

|

Emerging growth company |

|

If an emerging growth company, indicate by check mark if the registrant has elected not to use the extended transition period for complying with any new or revised financial accounting standards provided pursuant to Section 13(a) of the Exchange Act.

Indicate by check mark whether the registrant has filed a report on and attestation to its management’s assessment of the effectiveness of its internal control over financial reporting under Section 404(b) of the Sarbanes-Oxley Act (15 U.S.C. 7262(b)) by the registered public accounting firm that prepared or issued its audit report.

Indicate by check mark whether the registrant is a shell company (as defined in Rule 12b-2 of the Exchange Act). YES

The aggregate market value of common stock held by non-affiliates of the registrant computed by reference to the price of the registrant’s common stock as of June 30, 2021, the last business day of the registrant’s most recently completed second fiscal quarter, was approximately $

As of March 24, 2022, there were

DOCUMENTS INCORPORATED BY REFERENCE

Portions of the registrant’s proxy statement for the 2022 annual meeting of stockholders to be filed pursuant to Regulation 14A within 120 days after the registrant’s fiscal year ended December 31, 2021, are incorporated by reference in Part III of this Form 10-K.

Table of Contents

|

|

Page |

|

|

|

Item 1. |

3 |

|

Item 1A. |

46 |

|

Item 1B. |

99 |

|

Item 2. |

99 |

|

Item 3. |

99 |

|

Item 4. |

99 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Item 5. |

100 |

|

Item 6. |

100 |

|

Item 7. |

Management’s Discussion and Analysis of Financial Condition and Results of Operations |

101 |

Item 7A. |

113 |

|

Item 8. |

114 |

|

Item 9. |

Changes in and Disagreements with Accountants on Accounting and Financial Disclosure |

149 |

Item 9A. |

149 |

|

Item 9B. |

150 |

|

Item 9C. |

Disclosure Regarding Foreign Jurisdictions that Prevent Inspections |

151 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Item 10. |

152 |

|

Item 11. |

152 |

|

Item 12. |

Security Ownership of Certain Beneficial Owners and Management and Related Stockholder Matters |

152 |

Item 13. |

Certain Relationships and Related Transactions, and Director Independence |

152 |

Item 14. |

152 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Item 15. |

153 |

|

Item 16. |

154 |

i

SPECIAL NOTE REGARDING FORWARD-LOOKING STATEMENTS

This Annual Report on Form 10-K contains forward-looking statements that involve risks and uncertainties. All statements other than statements of historical facts contained in this Annual Report on Form 10-K are forward-looking statements. In some cases, you can identify forward-looking statements by words such as “anticipate,” “believe,” “contemplate,” “continue,” “could,” “estimate,” “expect,” “intend,” “may,” “plan,” “potential,” “predict,” “project,” “seek,” “should,” “target,” “will” or “would,” or the negative of these words or other comparable terminology. These forward-looking statements include, but are not limited to, statements about:

These forward-looking statements are based on our management’s current expectations, estimates, forecasts and projections about our business and the industry in which we operate, and management’s beliefs and assumptions and are not guarantees of future performance or development. These forward-looking statements are subject to a number of risks, uncertainties and assumptions, including those described under “Risk Factors” and elsewhere in this report. Moreover, we operate in a very competitive and rapidly changing environment, and new risks emerge from time to time. It is not possible for our management to predict all risks, nor can we assess the impact of all factors on our business or the extent to which any factor, or combination of factors, may cause actual results to differ materially from those contained in any forward-looking statements we may make. In light of these risks, uncertainties and assumptions, the forward-looking events and circumstances discussed in this report may not occur and actual results could differ materially and adversely from those anticipated or implied in the forward-looking statements.

In addition, statements that “we believe” and similar statements reflect our beliefs and opinions on the relevant subject. These statements are based upon information available to us as of the date of this report, and while we believe such information forms a reasonable basis for such statements, such information may be limited or incomplete, and our statements should not be read to indicate that we have conducted an exhaustive inquiry into, or review of, all potentially available relevant information. These statements are inherently uncertain and investors are cautioned not to unduly rely upon these statements.

1

SPECIAL NOTE REGARDING COMPANY REFERENCES

Unless the context otherwise requires, references in this Annual Report on Form 10-K to “FTG,” the “Company,” “we,” “us” and “our” refer to Finch Therapeutics Group, Inc. and its subsidiaries.

SPECIAL NOTE REGARDING TRADEMARKS

All trademarks, trade names and service marks appearing in this Annual Report on Form 10-K are the property of their respective owners.

RISK FACTORS SUMMARY

The following is a summary of the principal risks that could adversely affect our business, financial condition, operating results, cash flows or stock price. Discussion of the risks listed below, and other risks that we face, are discussed in the section titled “Risk Factors” in Part I, Item 1A of this Annual Report on Form 10-K.

2

PART I

Item 1. Business.

Overview

We are a clinical-stage microbiome therapeutics company leveraging our Human-First Discovery platform to develop a novel class of orally administered biological drugs. The microbiome consists of trillions of microbes that live symbiotically in and on every human and are essential to our health. When key microbes are lost, the resulting dysbiosis can increase susceptibility to immune disorders, infections, neurological conditions, cancer and other serious diseases. We are developing novel therapeutics designed to deliver missing microbes and their clinically relevant biochemical functions to correct dysbiosis and the diseases that emerge from it. Our Human-First Discovery platform uses reverse translation to identify diseases of dysbiosis and to design microbiome therapeutics that address them. We believe that our differentiated platform, rich pipeline and the broad therapeutic potential of this new field of medicine position us to transform care for a wide range of unmet medical needs.

Our lead product candidate, CP101, is an orally administered complete microbiome therapeutic in development for the prevention of recurrent Clostridioides difficile infection, or CDI. In June 2020, we reported positive topline data from our Phase 2 placebo-controlled clinical trial of CP101 for the prevention of recurrent CDI, which we refer to as the PRISM3 trial, and in November 2021, we reported positive topline data from our open-label, Phase 2 clinical trial of CP101 for the prevention of recurrent CDI, which we refer to as the PRISM-EXT trial. We have designed a Phase 3 clinical trial, which we refer to as the PRISM4 trial, to serve as our second pivotal trial of CP101 for the prevention of recurrent CDI. On March 1, 2022, we announced that enrollment in PRISM4 was paused following receipt of a clinical hold letter on February 24, 2022 from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, or the FDA, in connection with our investigational new drug application, or IND, for CP101, requesting additional information regarding our SARS-CoV-2 donor screening protocols, including, among other things, that we address the risk of SARS-CoV-2 transmission in the informed consent process, additional detail on how samples are shipped to the vendor performing the SARS-CoV-2 testing of the donor material and how inconclusive test results will be handled. We are also preparing to initiate a Phase 1b clinical trial of FIN-211 in autism spectrum disorder, or ASD; however, because FIN-211 includes donor-derived components, the clinical hold related to our IND for CP101 will also delay initiation of our clinical trial in ASD. We plan to manufacture additional lots of CP101 and FIN-211 to satisfy the FDA's requests related to SARS-CoV-2 screening and testing. We are currently evaluating the extent of the delay the clinical hold and related manufacturing activities will have on the timing for our clinical trials in CDI and ASD, which we expect to be at least one quarter based on manufacturing timelines; we describe the clinical hold and related matters further in the section entitled “Our Clinical Programs”.

CP101: Our Lead Product Candidate for the Prevention of Recurrent CDI

Our lead candidate, CP101, consists of a microbial community harvested from rigorously screened healthy donors that is lyophilized and formulated in orally administered capsules designed to release at the appropriate location in the gastrointestinal tract. CP101 is designed to deliver a complete microbiome, addressing the community-level dysbiosis that characterizes CDI. Patients with CDI suffer from severe diarrhea, which can progress to toxic megacolon and death, with more than 44,000 CDI-attributable deaths annually in the United States. In addition to the human cost, the economic impact of CDI is significant, with 2.4 million in-patient days and more than $5 billion in direct treatment costs each year in the United States alone. CDI often returns after cessation of antibiotic treatment because antibiotics do not address the dysbiosis that underlies this disease. We estimate there are approximately 200,000 cases of recurrent CDI annually in the United States.

In June 2020, we announced that PRISM3, the first pivotal trial of CP101, which was a randomized, blinded, placebo-controlled multi-center Phase 2 clinical trial, met its primary efficacy endpoint. Overall, 74.5% of participants who received a single administration of CP101 achieved a sustained clinical cure, defined as the absence of CDI through week 8, achieving statistical significance for the primary efficacy endpoint, with a clinically meaningful 33.8% relative risk reduction for CDI recurrence compared to placebo. In October 2021, we shared additional data from PRISM3 showing that the proportion of participants with sustained clinical cure (defined as absence of CDI recurrence) through week 24 remained significantly higher in the CP101 arm compared to the placebo arm. In PRISM3, the prevalence of adverse events was similar across CP101 and placebo arms, with no treatment-related serious adverse events in the CP101 arm.

In November 2021, we announced positive topline results from the 132-participant PRISM-EXT trial. The primary efficacy endpoint of the PRISM-EXT trial was sustained clinical cure (defined as absence of CDI recurrence) through 8 weeks post-treatment. Overall, 80.3% of participants who received a single oral administration of CP101 following standard-of-care, or SOC, antibiotics in PRISM-EXT achieved sustained clinical cure through week 8. At week 24, 78.8% of participants had

3

sustained clinical cure. In the PRISM-EXT trial, there were no treatment-related serious adverse events reported and CP101 exhibited an overall safety profile consistent with the profile observed in PRISM3. The PRISM-EXT results are consistent with and build on our previously reported PRISM3 results.

CP101 Program for the Treatment of Chronic HBV

Following a strategic review of our pipeline and business, we announced in March 2022 the decision to pause the development of CP101 for the treatment of chronic hepatitis B virus, or HBV. We believe this decision will allow us to maximize our working capital available for investment in our wholly-owned recurrent CDI and ASD programs. We may continue our research efforts in HBV in the future as our portfolio continues to mature.

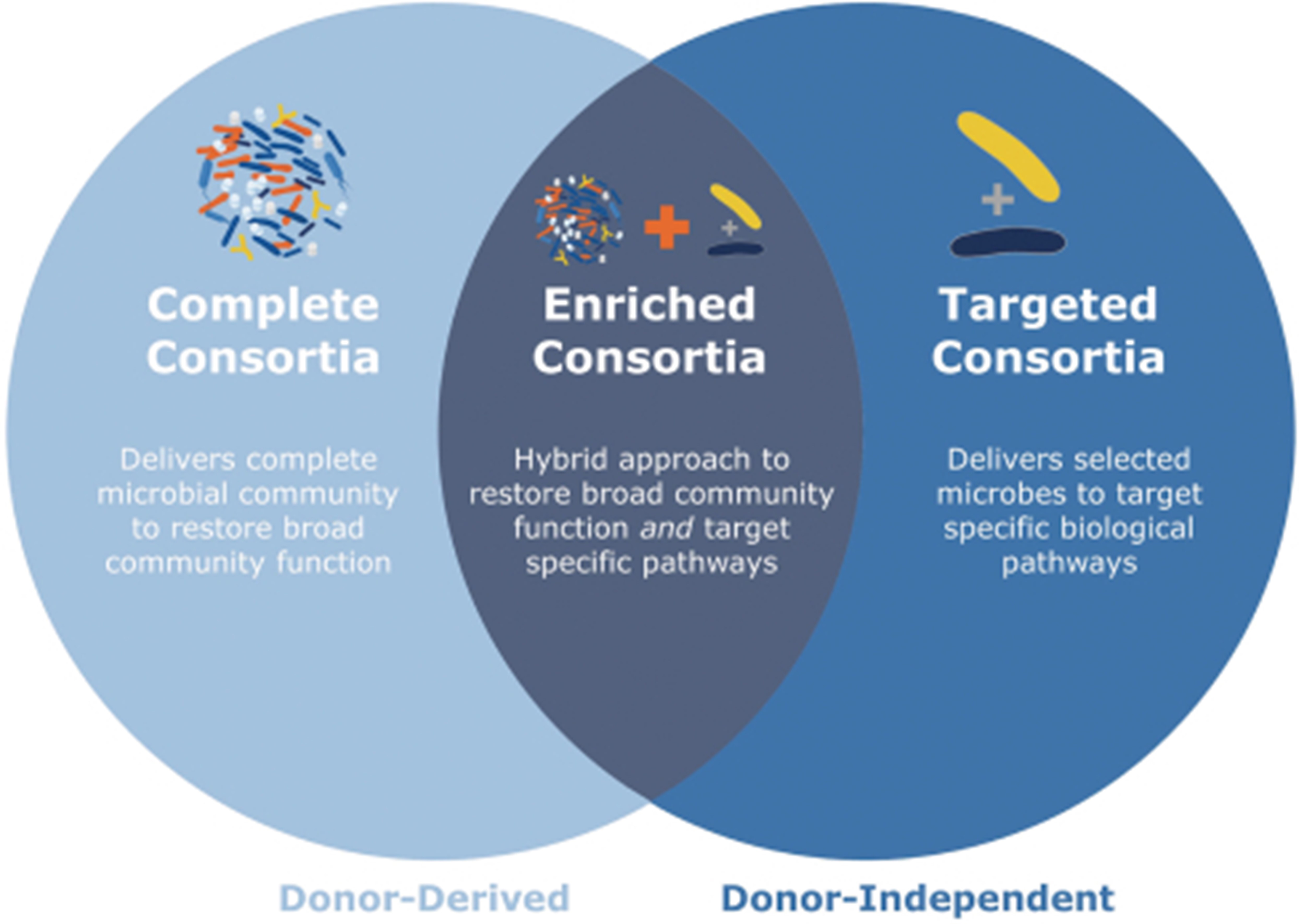

Developing Capabilities for Targeted and Enriched Consortia Product Candidates

In addition to developing CP101, a Complete Consortia product candidate designed to address community-level dysbiosis, or disruption across many functional pathways and species, we are also developing Targeted Consortia product candidates that consist of individual bacteria grown from master cell banks to engage narrower pathway-level dysbiosis. The ability to pursue both of these product strategies enables us to tailor our product candidates to the pathophysiology of each indication. This combination of capabilities also enables us to pursue a third product strategy, Enriched Consortia, which addresses dysbiosis at both the community and pathway level. These product strategies are summarized in the schema below:

Our Human-First Discovery platform informs each of these product strategies using clinical interventional data, through a process of reverse translation. Core to this strategy is our ability to deploy our proprietary machine learning algorithms to mine clinical data generated internally and by third parties, including experience with fecal microbiota transplantation, or FMT, a procedure that has been used to restore the gut microbiome and address community-level dysbiosis. FMT is a procedure, not a product. It is not approved by the FDA, and there are no standards for testing, processing and delivery of FMT, though it typically requires a colonoscopy. Despite these limitations, FMT has been used to treat more than 60,000 patients, with hundreds of clinical studies ongoing across a range of disease areas. We believe that this data can be used to (1) identify diseases where addressing dysbiosis provides therapeutic benefit, (2) reveal the mechanisms that underlie these results and (3) uncover key microbes and functional pathways that drive these clinical outcomes. We believe this reverse translation strategy is the optimal approach to developing microbiome therapeutics, providing causal insights that cannot be gleaned from preclinical in vitro or in vivo experiments alone. We further believe that we are uniquely positioned to execute

4

on this strategy because of our proprietary FMT database and biorepository, our broad network of collaborators that supports the rapid growth of our data assets and our proprietary machine learning algorithms that enable the efficient translation of clinical data into therapeutic insights.

FIN-211: Our Product Candidate to Address Gastrointestinal and Behavioral Symptoms of ASD

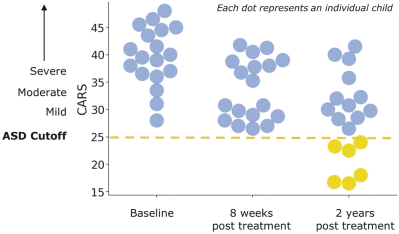

We have used our Human-First Discovery platform to develop FIN-211, an Enriched Consortia product candidate that we are advancing to address the gastrointestinal and behavioral symptoms of ASD. Scientific research in human and animal models have highlighted the “gut-brain axis” linking dysbiosis to neurological and neurobehavioral conditions, as the microbiome impacts the enteric nervous system and the production of neurotransmitters. This basic research is supported by a growing body of third-party clinical research. An open-label, proof-of-concept FMT trial observed that, two years after treatment, 33% of the study participants who had previously been diagnosed with ASD were below the ASD diagnostic cutoff score for the Childhood Autism Rating Scale (CARS), a commonly used ASD diagnostic tool. In another open-label randomized, controlled trial, children with ASD receiving FMT and behavioral therapy showed a statistically significant improvement in their behavioral symptoms compared to those receiving behavioral therapy alone. Both studies also observed marked improvements in the gastrointestinal symptoms that many autistic children suffer from. There are no FDA-approved therapies for the core symptoms of ASD and the total financial burden of care for this condition is estimated to exceed $100 billion in the United States annually. We have received feedback from the FDA that demonstrating a benefit for either gastrointestinal or behavioral symptoms of ASD could support a biologics license application. Building on our discussions with the FDA, we aim to continue to validate behavioral instruments as part of our clinical development plans. We have designed FIN-211 to address both behavioral and gastrointestinal aspects of ASD, which we plan to assess, along with safety and tolerability, in a Phase 1b clinical trial of FIN-211 in ASD. We believe FIN-211 has the potential to transform care for patients with ASD.

TAK-524 (formerly FIN-524) Ulcerative Colitis Development Program in Collaboration with Takeda

In collaboration with Takeda Pharmaceutical Company Limited, or Takeda, we are also developing Targeted Consortia product candidates for inflammatory bowel disease. In August 2021, we announced that Takeda elected to accelerate its leadership role in the FIN-524 ulcerative colitis development program, now known as TAK-524. Accordingly, we transferred the program to Takeda for further development. The design of product candidate TAK-524 leverages computational and molecular analysis of data from 146 patients treated with FMT and 19 observational studies of an additional 2,210 patients. We believe that the development program for TAK-524, which is a Targeted Consortia product candidate composed of strains grown from master cell banks, is not affected by the clinical hold related to our IND for CP101.

FIN-525 for the Treatment of Crohn's Disease in Collaboration with Takeda

We continue to partner with Takeda on discovery efforts targeting the development of FIN-525 for the treatment of Crohn’s disease. We believe that the development program for FIN-525, which is a Targeted Consortia product candidate composed of strains grown from master cell banks, is not affected by the clinical hold related to our IND for CP101.

5

Our Pipeline

6

The Human Microbiome and its Impact on Disease

The human microbiome describes the community of more than 30 trillion microbes that reside on and inside the human body. By evolving together over millions of years, microbes and humans have developed an intricate and mutually beneficial relationship that has only recently been uncovered. Enabled by the genomic revolution, researchers have discovered that humans carry over 1,000-fold more microbial genes than host genes and that microbiome signaling is fundamentally intertwined with many aspects of human physiology ranging from immune and metabolic functions to neurological function and reproductive health. The deep inter-relationship between microbes and their human hosts is a co-evolution that has resulted in a learned dependency, leaving humans now reliant on inputs from this previously unrecognized organ system.

Disruption of the gut microbiome is associated with a large number of diseases that have dramatically increased in prevalence among populations in developed countries over the past century. We believe these epidemiological trends are linked to changes in the microbiome, which if reversed could potentially address an underlying cause of these diseases and change the epidemiology as a result. The rise of these chronic illnesses coincides with our adoption of a number of practices that disrupt the microbiome: more than 42 billion doses of antibiotics are administered annually, many killing 40-60% of microbial species in the gut; a third of babies in the United States today are born by caesarean sections, and are consequently unable to inherit this organ from their mother; and a highly sanitized and artificial environment, absent the environmental inputs expected by our microbiome, applies further pressure on this ecosystem within us. The effects of these environmental inputs coalesce around the gut microbiome resulting in dysbiosis and these changes are linked to a wide variety of chronic diseases. For example, antibiotic exposure doubles the risk of developing IBD, as well as significantly increases the risk of developing over 10 types of cancer. Early microbiome disruption is also associated with ASD, autoimmune indications such as celiac diseases, and allergies and asthma, and microbiome disruption later in life has been linked to neurodegenerative diseases, including Alzheimer’s disease and Parkinson’s disease. Importantly, in multiple animal models, these diseases can be induced by microbiome disruption and corrected by restoration, providing evidence of causality. For several of these therapeutic areas, this has been further bolstered by clinical data with FMT.

The effects of gut microbiome dysbiosis reverberates throughout the body, both because immune cells are heavily concentrated in the gut, where more than 70% of the body’s immune cells are located, and because microbial metabolites enter systemic circulation, acting on organs throughout the body. For example, researchers at the California Institute of Technology showed that the transfer of the microbiome from human donors with ASD into microbiome-free mice promoted hallmark autistic behaviors. In addition, a large body of research has documented the connection between over a dozen different microbiome species and molecular pathways connecting the gut’s enteric nervous system to the brain. We believe the gut-brain axis is but one example of how the microbiome can provide therapeutic benefits to diseases beyond the gut.

Restoring the microbiome, or its inputs, is an opportunity to directly address the underlying causes of many diseases driven by dysbiosis. Many existing drugs target only the downstream symptoms of disease, for example, anti-tumor necrosis factor, or anti-TNF, biologics are prescribed to IBD patients to suppress systemic immunity, without addressing the underlying drivers of gut inflammation and immune dysregulation. This can lead to unintended side effects as well as an incomplete resolution of disease. Treating the root cause of disease is more likely to deliver a therapeutic breakthrough and for many diseases of dysbiosis, we believe that only through the restoration of the critical physiological role of the microbiome organ can this be achieved. Currently there are no microbiome therapeutics approved by the FDA. We believe that our ability to target both community- and pathway-level dysbiosis through our Human-First Discovery platform uniquely positions us to deliver on this transformational opportunity to improve human health through microbiome therapeutics.

7

Our Approach

We develop microbiome therapeutics following a three-stage process that combines aspects of traditional drug development with the unique opportunities enabled by our platform. In the first stage, Human-First Discovery, we use human data to identify promising clinical indications, microbial mechanisms and a consortia that engages these mechanisms. The second stage consists of IND-enabling activities, including bioprocess and formulation development, quality control and current Good Manufacturing Practices, or cGMP, production. The third stage is clinical development, in which we leverage customized pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic assays to understand optimal dosing and delivery. Importantly, data from clinical development can feed directly back into Human-First Discovery, enabling iterative development of differentiated follow-on product candidates.

8

9

Our Clinical Programs

CP101 for the Treatment of Recurrent CDI

Overview

Our lead product candidate, CP101, is an orally administered, complete microbiome therapeutic capsule designed to deliver an intact, functional microbiome to durably repair community-level dysbiosis. CP101 contains microbial communities harvested from rigorously screened, healthy human stool samples that have been purified, tested, stabilized, characterized and formulated in acid-resistant capsules to facilitate intestinal release after passage through the stomach.

Pathogen exclusion in CP101 is based on proprietary testing and characterization technology developed through discussions with the FDA; unlike other orally administered microbiome therapeutic candidates in development, it does not rely on non-specific biocides such as ethanol, which inactivate both beneficial and potentially pathogenic bacteria. Instead, our technology enables us to identify suitable microbial communities prior to manufacture, without requiring destructive interference in the healthy community needed to repair community-level dysbiosis. This enables CP101 to deliver a complete consortium of microbial communities rather than narrow and variable subsets of the microbiome. Our product qualification strategy is supported by the proprietary chemistry and processing techniques that optimize community viability during lyophilization, processing and administration. This fully integrated manufacturing process is designed to consistently deliver a complete microbiome.

Our production process for CP101 is designed to be scalable. We typically collect many samples from each donor and we are able to produce many treatments from each sample collected. As a result, a small pool of donors can support a large production base. For example, we believe a pool of 200 active donors could support production of approximately 100,000 treatments of CP101 annually. Furthermore, our process is designed to yield a favorable stability profile, with at least 24 months of stability at 2°–8°C and up to six months of stability at 25°C to allow for temperature excursions during delivery and administration. We believe this favorable stability profile will simplify supply chain logistics and enable more convenient care. CP101 has received Fast Track designation and Breakthrough Therapy designation from the FDA for the prevention of recurrent Clostridioides difficile infection, or recurrent CDI. Breakthrough Therapy designation provides expedited review and access to collaborate with the FDA on rapid development of CP101.

Clinical Hold

Following receipt of a clinical hold letter from the FDA related to our IND for CP101 on February 24, 2022, or the February 2022 Clinical Hold Letter, we paused enrollment in PRISM4, our Phase 3 clinical trial of CP101 in recurrent CDI. In the February 2022 Clinical Hold Letter, the FDA requested additional information about our SARS-CoV-2 donor screening protocols, including, for example, additional detail on how samples are shipped to the vendor performing the SARS-CoV-2 testing of the donor material and how inconclusive test results will be handled, as well as updating the informed consent process to address the risk of SARS-CoV-2 transmission, including, for example, the limitations of laboratory screening.

In March 2020, at the outset of the COVID-19 pandemic, the FDA issued a public safety alert regarding the potential risk of transmission of SARS-CoV-2 virus through the use of donor-derived investigational microbiome therapies and the need for additional safety precautions. At that time, the FDA placed our IND for CP101 on partial clinical hold, requiring us to implement new SARS-CoV-2 screening measures for any microbiota material donated on or after December 1, 2019 and to address the risk of SARS-CoV-2 transmission in the informed consent process. At that time, the FDA also placed the IND of OpenBiome, a manufacturer that we had contracted with to produce clinical raw material, on a partial clinical hold for the same reasons. Notwithstanding the partial clinical hold notices, we were able to continue dosing patients in our then-ongoing PRISM-EXT trial of CP101 in recurrent CDI as all of the CP101 lots used for PRISM-EXT were manufactured from material donated prior to December 1, 2019.

In January 2021, OpenBiome was released from partial clinical hold after implementing, among other things, a direct testing method for SARS-CoV-2. In March 2021, we acquired certain manufacturing assets from OpenBiome, and in November

10

2021, we began dosing participants in PRISM4 with CP101 lots that had been screened for SARS-CoV-2 using the same testing method and vendor used by OpenBiome.

Following communications with the FDA in January 2022, on February 24, 2022, the FDA sent the February 2022 Clinical Hold Letter to us stating that the FDA required additional information about our SARS-CoV-2 screening protocols and related informed consent language, and that a clinical hold remains in effect until the FDA's requests have been satisfactorily addressed. The February 2022 Clinical Hold Letter did not reference any adverse clinical outcome experienced in any of our clinical trials. We have informed the FDA that participants were dosed in PRISM4 while the clinical hold was in effect and we are conducting a quality investigation of the matter. We are communicating with the FDA regarding the quality investigation, and we have committed to addressing any relevant findings prior to proceeding with enrollment in PRISM4. We have submitted a Complete Response to the February 2022 Clinical Hold Letter and we are communicating with the FDA to resolve the clinical hold as soon as possible.

On March 17, 2022, we received an additional letter from the FDA, or the March 2022 Letter, requesting changes to the testing algorithm used to diagnose suspected CDI recurrences in PRISM4, as well as additional information about the proposed statistical analysis plan for PRISM4 and the validation package for one of our release tests. We are unable to proceed with enrollment in PRISM4 until the FDA removes the clinical hold, we address findings from our related quality investigation, we complete related manufacturing activities to satisfy the FDA's requests related to SARS-CoV-2 screening and testing (which includes manufacturing additional lots of CP101), and we satisfactorily address the matters raised in the March 2022 Letter. We are currently evaluating the extent of the delay these activities will have on the anticipated timing for resuming enrollment in PRISM4 and, based on manufacturing timelines, we expect at least a one-quarter delay.

Indication Overview

Clostridioides difficile, or C. difficile, is a toxin-producing, spore-forming bacterium that causes severe and persistent diarrhea in infected individuals. C. difficile expresses toxins that lead to inflammation of the colon, severe diarrhea and abdominal pain, as well as potentially more serious clinical outcomes including toxic megacolon, perforation of the colon, and death. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention considers CDI to be one of the top five most urgent antibiotic resistant threats and the most common healthcare-associated infection in the United States. We estimate that there are over 450,000 cases of primary CDI and approximately 200,000 cases of recurrent CDI annually in the United States, collectively resulting in more than 44,000 CDI-attributable death per year. In addition to this human toll, the economic impact is substantial, with 2.4 million inpatient days and greater than $5 billion in direct treatment costs each year in the United States. Between 2001 and 2012, there was an increase in the annual CDI incidence of 43%; however, cases of multiply recurrent CDI increased 188% over that same period.

Rationale for Microbiome Therapeutics in Recurrent CDI

Dysbiosis: Observational clinical data suggests that patients with recurrent CDI have significant community-level dysbiosis compared to healthy controls, with reduced microbiome diversity, in part, due to the many courses of antibiotics that are typically used to treat these patients. Initial episodes of CDI are predominantly linked to treatment with antibiotics, creating a direct link between dysbiosis and disease onset.

Mechanism of Action: The microbiome plays an important role in the pathophysiology of recurrent CDI, and third-party preclinical models and human studies support our understanding of this mechanism. Among healthy individuals, an intact microbiome outcompetes C. difficile for its main energy source, primary bile acids produced by the host. This competitive exclusion enabled by an intact microbiome is described as colonization resistance. However, when there is community-level dysbiosis and competitors are eliminated, C. difficile, typically a poor competitor for bile acid metabolism, is able to overcome colonization resistance, resulting in infection. In addition to competing for resources, a healthy microbiome generates microbiome-derived secondary bile acids that inhibit residual C. difficile spores from germinating into their vegetative, toxin-producing form. Organisms that are able to convert primary bile acids into C. difficile-inhibiting secondary bile acids remove a food resource (primary bile acids) and create a potent inhibitor of toxin production (secondary bile acids). Antibiotics are able to suppress vegetative, toxin-producing C. difficile, but residual C. difficile spores are not susceptible to antibiotics and are able to persist. Accordingly, when an antibiotic course is complete, the residual C. difficile spores can germinate into vegetative, toxin-producing C. difficile, driving CDI recurrence, a key element of morbidity, mortality and cost in CDI care. Until the underlying microbiome dysbiosis is addressed, patients remain susceptible to CDI recurrence.

11

Third-Party Clinical Data: Numerous cohort studies, observations from clinical practice and small randomized clinical trials have demonstrated that FMT is able to prevent recurrent CDI. CP101 builds on these human data that suggest repairing community-level dysbiosis may restore colonization resistance and break the cycle of CDI recurrence.

Existing Therapeutics and Their Limitations

Antibiotics

Although antibiotics are considered standard of care to treat CDI, they also impair the diversity of the resident microbiome, affording a potential microbial niche for resident C. difficile spores to germinate into toxin-producing cells. Recurrence rates following antibiotic therapy are high as these agents exacerbate community-level dysbiosis. A commonly used CDI antibiotic, vancomycin, is non-specific and causes significant disruption to the microbiome. New generation medications, such as fidaxomicin, were designed as an alternative, narrow-spectrum antibiotic, with reduced activity against other microbes compared to vancomycin. Increasingly sophisticated and precision-targeted antibiotics can mitigate further harm to the microbiome but they do not address what we believe to be the root cause of recurrent CDI—the dysbiosis caused by antimicrobials.

Antibodies

Bezlotoxumab is an approved intravenous monoclonal antibody product that targets the toxins produced by C. difficile. However, like antibiotic therapy, it fails to repair dysbiosis, the underlying cause of recurrent CDI.

Probiotics

Probiotics are dietary supplements or foods that contain microbes and are typically derived from fermented foods such as yogurt. However, probiotics are not designed to durably colonize the human intestine and no clinical trials have demonstrated durable repair of dysbiosis with probiotics to date. Recent ACG guidelines have recommended against the use of probiotics for the prevention of CDI.

Fecal Microbiota Transplantation

FMT is the process of transplanting stool and accompanying microbes from healthy donors into patients suffering from diseases of dysbiosis. FMT has generated remarkable outcomes in CDI, supporting the rationale for targeting dysbiosis. However, FMT is a procedure, not a product, and often requires a colonoscopy for administration. There are no defined regulatory standards for screening, processing and delivery of FMT, and this treatment has not been approved by the FDA. There is no FDA-approved agent that addresses the community-level dysbiosis that underlies recurrent CDI.

Our Product Candidate: CP101

We have designed CP101 to break the cycle of CDI recurrence by restoring a complete microbiome. We believe that CP101 has the following advantages when compared to existing therapeutic approaches and other microbiome therapeutic candidates in development for the treatment of recurrent CDI:

12

Market Opportunity

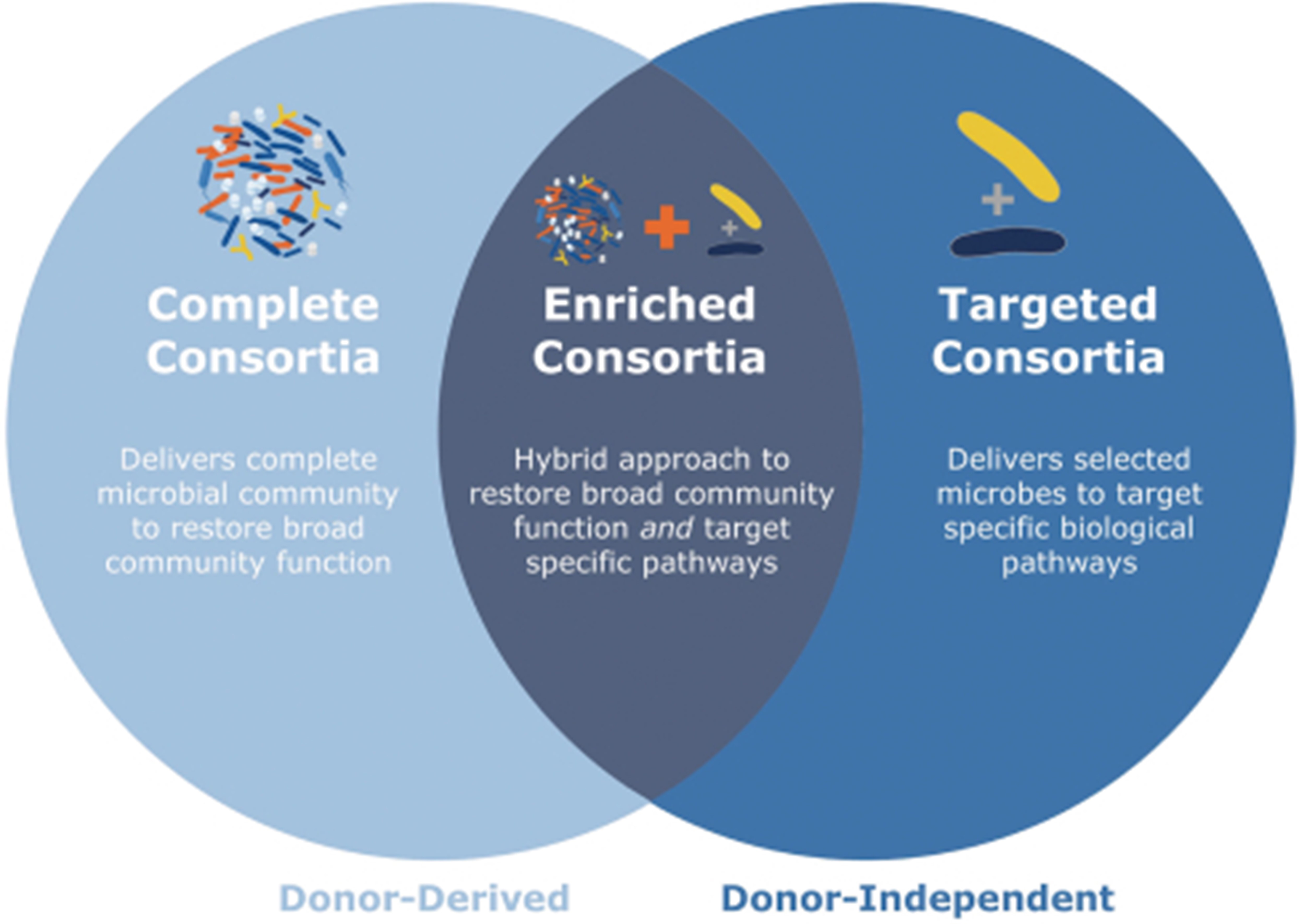

Recurrent CDI represents a robust market opportunity and we estimate there are approximately 200,000 cases each year in the United States. As shown in the figure below, the first recurrence of CDI represents more than half of these cases. Unlike pivotal trials for other microbiome programs, the PRISM3 trial design included first recurrence CDI for patients 65 years of age or older, demonstrating benefit in a broad patient population.

We expect that prescriptions of CP101 will be predominantly fulfilled in the outpatient setting, through the specialty pharmacy channel. While initial presentation of recurrent CDI may occur either in the hospital setting or in the outpatient setting, the majority of hospitalized patients are discharged while being treated with standard-of-care antibiotics, prior to when CP101 would be administered. We believe that this outpatient setting, which provides favorable pricing and reimbursement dynamics relative to the hospital setting, will allow us to better realize value in the recurrent CDI market opportunity.

Clinical Trials of CP101 for the Treatment of Recurrent CDI

Overview

The development of CP101 for the prevention of recurrent CDI is supported by positive topline results from a Phase 1 open-label clinical trial (n=49), a Phase 2 placebo-controlled clinical trial referred to as the PRISM3 trial (n=198), and a Phase 2 open-label clinical trial referred to as the PRISM-EXT trial (n=132), as further summarized elsewhere in this Annual Report. CP101 is currently in late-stage clinical development and being evaluated in a Phase 3 clinical trial, referred to as the

13

PRISM4 trial, anticipated to enroll approximately 300 participants. We plan to have further discussions with the FDA regarding the size and make-up of the safety database for CP101, which could result in the need for additional studies. PRISM4 is currently on clinical hold, pending product availability and resolution of matters related to the February 2022 Clinical Hold Letter and the March 2022 Letter.

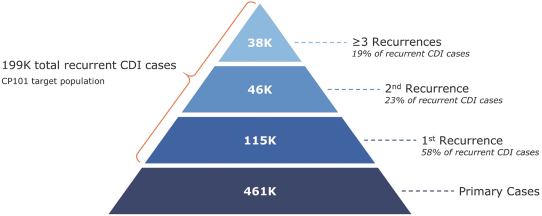

PRISM4 Trial

We have designed a Phase 3 clinical trial, which we refer to as the PRISM4 trial, to serve as our second pivotal trial of CP101 for the prevention of recurrent CDI. The PRISM4 trial is a multi-center trial expected to enroll approximately 300 adult participants with recurrent CDI. PRISM4 has two parts: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled part (Part A) and an optional, open-label treatment part (Part B). In Part A, eligible participants will be randomized in a 2:1 ratio to receive either a one-time oral administration of CP101 or placebo after completing standard-of-care, or SOC, CDI antibiotics for their most recent CDI recurrence. The primary efficacy endpoint of the trial will be CDI recurrence through 8 weeks post-treatment. The primary safety endpoint is the incidence of treatment emergent adverse events through week 8. Secondary endpoints include safety and CDI recurrence through 24 weeks post-treatment. The design of Part A is shown below.

PRISM4 Part A Trial Design

Like our previously completed PRISM3 Phase 2 clinical trial, the PRISM4 trial will enroll participants with recurrent CDI, including participants experiencing their first CDI recurrence that are 65 years of age or older. At study entry, all guideline recommended test methods for C. difficile, including PCR- or toxin EIA-based test methods, will be accepted for the diagnosis of the qualifying episode of CDI.

Participants in Part A of the PRISM4 trial that experience a CDI recurrence within 8 weeks of randomization will have the option to enroll in the open-label, Part B component of the trial, in which they will receive CP101 following completion of SOC antibiotics.

On March 1, 2022, we announced that enrollment in PRISM4 was paused following receipt of the February 2022 Clinical Hold Letter. We have submitted a Complete Response to the February 2022 Clinical Hold Letter and we are communicating with the FDA to resolve the clinical hold and related matters, as described above in the section entitled "Clinical Hold".

PRISM3 Trial

We evaluated CP101 for the treatment of recurrent CDI in our pivotal PRISM3 trial, which represents the first positive pivotal trial with an orally administered complete microbiome product candidate. PRISM3 was a Phase 2, 1:1 randomized, placebo-controlled, multi-national trial designed to demonstrate the superiority of CP101 following standard-of-care CDI antibiotics compared to antibiotics alone in preventing recurrence among patients with recurrent CDI. A total of 206 participants were enrolled across 51 sites, of which 198 were evaluable. Patients were recruited from across all stages of recurrent CDI, including patients experiencing their first recurrence that were 65 years of age or older. Qualifying episodes of recurrent CDI were diagnosed using all standard-of-care laboratory tests, including PCR- or toxin EIA-based test methods. All participants were treated with standard-of-care CDI antibiotic therapy prior to randomization. Following antibiotic treatment, participants were randomized to receive either a one-time oral administration of CP101 or a placebo, without the need for bowel preparation. The trial design is shown below.

14

PRISM3 Trial Design

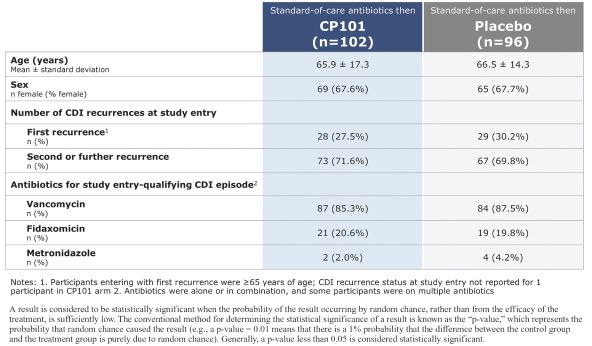

Baseline characteristics were balanced between the two study arms, with no meaningful clinical differences. Participants with a first CDI recurrence at study entry represented approximately 30% of the study population.

Treatment Groups Had No Meaningful Clinical Differences at Baseline

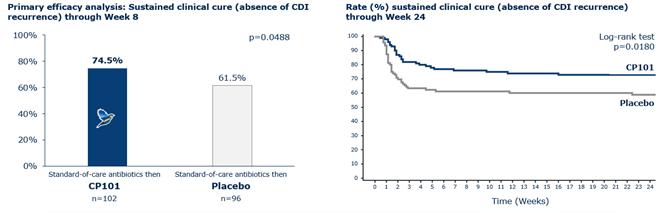

PRISM3 achieved its primary efficacy endpoint, which was sustained clinical cure defined as the absence of CDI recurrence through eight weeks following administration of study drug. Sustained clinical cure was determined by a blinded adjudication board of independent experts evaluating the totality of clinical and laboratory data including central laboratory data with PCR, toxin EIA and toxigenic culture testing. Following standard-of-care CDI antibiotics, 74.5% of participants treated with CP101 achieved sustained clinical cure, a statistically significant improvement over those receiving placebo (61.5%; p=0.0488), meeting the primary efficacy endpoint and representing a clinically meaningful 33.8% relative risk reduction for CDI recurrence, as shown below on the left. On long-term assessment, CP101 demonstrated clinically meaningful durability and the proportion of participants with sustained clinical cure, defined as the absence of CDI recurrence, through Week 24 remained significantly higher in the CP101 arm compared to placebo (73.5% [75/102] vs 59.4% [57/96], p=0.0347). Time-to-event analysis through Week 24 showed a statistically significant and durable benefit, favoring CP101 compared to placebo (p=0.018), as shown below on the right.

15

CP101 Achieved 33.8% Relative Risk Reduction for CDI Recurrence in PRISM3 |

Sustained Clinical Cure at Week 8 Was Maintained Through Week 24 in PRISM3 |

PRISM3 Extension Trial

PRISM-EXT was an open-label Phase 2 clinical trial evaluating the safety and efficacy of CP101 for the prevention of recurrent CDI. Initially, the study only enrolled participants who had previously enrolled in the randomized, placebo-controlled PRISM3 trial and experienced a CDI recurrence. After PRISM3 enrollment was complete, a protocol amendment expanded the inclusion criteria to allow participants with recurrent CDI to enroll directly in PRISM-EXT without having previously enrolled in PRISM3. The trial design is shown below.

PRISM3 Extension Trial Design

In November 2021, we reported positive topline results from the PRISM-EXT trial. A total of 132 participants were analyzed, including one cohort that directly enrolled in the trial following a recent CDI recurrence without having previously participated in PRISM3 (n=82) and one cohort that enrolled after experiencing a CDI recurrence following administration of placebo or a single dose of CP101 in PRISM3 (n=50). The primary efficacy endpoint was sustained clinical cure (defined as absence of CDI recurrence) through 8 weeks post-treatment. Overall, 80.3% of participants who received a single oral administration of CP101 following standard-of-care antibiotics in PRISM-EXT achieved sustained clinical cure (defined as absence of CDI recurrence) through week 8 and 78.8% had sustained clinical cure through week 24, as shown below. The PRISM-EXT results are consistent with and build on the previously reported PRISM3 results.

16

CP101 Demonstrated Robust Sustained Clinical Cure in PRISM-EXT

Among the 102 participants who were treated with CP101 in PRISM3, 20 were enrolled in PRISM-EXT and treated with a second dose of CP101. Of the participants who received either a single dose of CP101 in PRISM3 (n=82) or a second dose by enrolling in PRISM-EXT (n=20), a post-hoc analysis shows that a total of 90 participants achieved sustained clinical cure through 8 weeks after their final dose, resulting in a cumulative efficacy of 88.2% (n=102).

Phase 1 Clinical Trials

The first clinical trial to evaluate CP101 for the treatment of recurrent CDI was a 49 patient, single-center, open-label Phase 1 clinical trial conducted at the University of Minnesota. The trial enrolled patients who had experienced two or more recurrences of CDI. The primary endpoint was the safety and tolerability of CP101. Clinical success was defined as absence of CDI recurrence within two months post-treatment. No related SAEs occurred and 43 of the 49 patients treated achieved clinical success, resulting in an efficacy rate of 87.8% after treatment with CP101. Because the study was designed with a single arm and did not have concurrent control participants, the statistical significance of the observed efficacy rate was not assessed in this study. Approximately a third of patients reported mild, transient gastrointestinal symptoms following the treatment. Multiple doses were evaluated in this first cohort, including a high dose range (1.25-2.5x1012) and a low dose range (2.1-2.5x1011), with no meaningful dose response at the dosing levels tested. An intermediate dose of 6x1011 was selected for further process development and tested in an additional 10-patient cohort at the University of Minnesota. In this second cohort, seven of ten patients achieved clinical success through eight weeks following CP101. These promising clinical results from Phase 1 were used to secure Fast Track designation and Breakthrough Therapy designation from the FDA.

Safety and Tolerability

CP101 has been well-tolerated throughout all stages of development to date, and there have been no treatment-related SAEs reported. In the PRISM3 safety population, treatment-emergent AEs and treatment-related AEs were similar between treatment groups, with 16.3% (17/104) of participants in the CP101 arm versus 19.2% (19/99) of participants in the placebo arm experiencing treatment-related adverse events, or AEs, through 24 weeks. In the CP101 arm, treatment-related AEs were mild (Grade 1: 16/17) and moderate (Grade 2: 1/17), and primarily gastrointestinal in nature.

The most common treatment-emergent AEs reported in the CP101 arm through week 8 were predominantly gastrointestinal symptoms, as shown in the table below. Among the five most common adverse events in the CP101 arm, four adverse events were observed more frequently in participants treated with placebo relative to participants treated with CP101. For instance, we observed significantly fewer participants with abdominal pain among those treated with CP101 (30.8%) relative to those treated with placebo (59.6%; p<0.0001).

17

Most Frequent Adverse Events in the PRISM3 CP101 Arm Through Week 8

Additionally, in the 132-participant PRISM-EXT trial, there were no treatment-related SAEs reported and CP101 exhibited an overall safety profile consistent with the profile observed in PRISM3.

Pharmacokinetics

We used data from these clinical trials to confirm potential mechanisms underlying the clinical outcomes observed with CP101 for recurrent CDI. We used high-throughput sequencing to characterize the engraftment of CP101 Taxa, or groups of genetically similar bacteria, among participants treated in the PRISM3 study. As expected, participants treated with CP101 had dramatically higher engraftment of CP101 Taxa than patients treated with placebo, as shown in the graphic below, highlighting our ability to effectively deliver a viable consortia to the appropriate location in the gastrointestinal tract with our targeted oral capsule.

CP101 Shows Significant Engraftment Overall |

|

|

We also observed a strong relationship between engraftment of the microbes delivered in CP101 and clinical outcomes in PRISM3. Among patients with successful engraftment at week 1 following CP101 administration, 96.0% achieved a sustained clinical cure, while 54.2% of those without successful engraftment at week 1 achieved a sustained clinical cure (p < 0.001).

18

CP101 Engraftment Shows a Bimodal Distribution |

CP101 Engraftment Correlates with Sustained Clinical Cure |

|

|

|

|

We believe one factor that may have reduced engraftment among some PRISM3 participants who received CP101 is the persistence of residual vancomycin, a broad spectrum antibiotic with activity against a number of CP101 microbes, prior to treatment with CP101. As part of the study protocol, all patients enrolled in PRISM3 completed a course of standard of care antibiotics, which could have included either vancomycin or fidaxomicin, prior to randomization and administration of study drug.

To limit the impact of residual standard of care antibiotics on CP101, participants in PRISM3 completed a minimum two-day antibiotic washout period prior to administration of study drug to provide time for antibiotic clearance from the colon. Recent scientific literature shows, however, that the stool concentration of vancomycin two days after cessation of administration remains at approximately 65% of peak concentrations and declines to approximately 15% of peak concentrations after a three-day washout. These data suggest that a two-day washout period may have been insufficient to clear residual vancomycin.

To address this limitation, we have extended the minimum antibiotic washout period prior to administration of CP101 in our PRISM4 trial from two days to four days.

Pharmacodynamics

We believe bile acid metabolism plays a key role in the pathogenesis of recurrent CDI. A healthy microbiome generates microbiome-derived secondary bile acids that inhibit residual C. difficile spores from germinating into their vegetative toxin-producing form. Patients with recurrent CDI have depleted secondary bile acids and a higher concentration of primary bile acids, a key energy source for C. difficile. There are eight microbial genes that are critical for the conversion of primary bile acids into secondary bile acids. We used high-throughput metagenomic sequencing to measure the presence of these genes before and after treatment with CP101. At baseline, we found participants with recurrent CDI had between zero and four of these genes, missing key components of the pathway. Among participants evaluated for pharmacodynamics in Phase 1 (n=5), we found that all participants had all eight genes at all timepoints measured after treatment with CP101, highlighting the ability of CP101 to restore an important pathway in the pathogenesis of recurrent CDI.

These data show that in keeping with similar host-targeted gene therapies, we are able to deliver a lasting transformation in the genetic capacity of the treated patient in a manner that improves clinical outcomes. With our treatment, however, we do not need to modify the host genome, instead we can deliver these genetic capabilities through microbes that are able to engraft and reproduce in the host. Importantly, because more than 99% of all genes found in humans are found in the microbiome, this opens a much broader suite of targets than those which are accessible through host-targeted gene therapies.

19

CP101 is Designed to Break the Cycle of CDI Recurrence by Restoring Bile Acid Metabolism

CP101 Restores Bile Acid Metabolism – A Key Biomarker for Treatment in Recurrent CDI

Chronic HBV

Following a strategic review of our pipeline and business, we announced in March 2022 the decision to pause the development of CP101 for the treatment of chronic HBV. We believe this decision will allow us to maximize our working capital available for investment in our wholly-owned recurrent CDI and ASD programs. We continue to believe that CP101, or other product candidates that we may develop in the future, may have the potential to treat chronic HBV, a chronic infection linked to microbiome dysbiosis. We may continue our research efforts in HBV in the future as our portfolio continues to mature.

FIN-211 to Address Symptoms of Autism Spectrum Disorder

Overview

FIN-211 is an orally administered, Enriched Consortia product candidate designed to deliver both a complete microbiome and targeted microbes not found in most healthy donors. We believe FIN-211 has the ability to address both the gastrointestinal and behavioral symptoms of autism spectrum disorder, or ASD.

Indication Overview

ASD is a behaviorally defined condition characterized by reduced social interaction, impaired communication skills and the presence of repetitive or restrictive behaviors. Beyond the core symptoms by which it is defined, ASD is recognized as a heterogeneous medical condition by the FDA, and patients can exhibit highly varied symptoms and behaviors such as irritability, heightened sensitivities and movement disorders. A subset of patients with ASD, comprising at least 30% of the

20

population, experience significant gastrointestinal symptoms, with the most common gastrointestinal symptom being constipation (ASD-C). There is a correlation between the severity of these gastrointestinal symptoms and the severity of behavioral symptoms. Standard treatments for constipation are often ineffective, which may be because the underlying biology of gastrointestinal symptoms is distinct in children with ASD compared to neurotypical children. We believe by addressing this underlying biology with a microbiome therapeutic, we will be able to improve ASD gastrointestinal symptom and neurobehavioral development.

The diagnosed prevalence of ASD is currently 1 in 44 for children in the United States, a prevalence that has increased substantially over the past few decades. Worldwide prevalence estimates vary but are thought to be similar in other developed countries. It is believed there are more than 4.6 million children and adults in the United States with ASD. By some estimates, the total financial burden of care for patients with ASD exceeds $100 billion in the United States annually.

Existing Therapeutics and Their Limitations

There is no FDA-approved pharmaceutical treatment for the core symptoms of ASD. The only widely accepted intervention with substantial supportive evidence is a form of long-term behavioral therapy, called Applied Behavioral Analysis, or ABA. Children with ASD usually begin ABA as soon as they are diagnosed, typically between ages 2-6 years, and are recommended to receive 30-40 hours of therapy every week. ABA may continue into adulthood and parents are often faced with making difficult choices between school or continuing ABA therapy. The only FDA-approved pharmaceutical treatment for ASD are anti-psychotics, which are only prescribed to treat the irritability that often accompanies ASD, but is not a core symptom of the disorder. While ASD-C may be treated with laxatives or enemas, these can be poorly tolerated and are often ineffective. As a result, a high unmet medical need remains across both gastrointestinal and behavioral symptoms.

Rationale for Microbiome Therapeutics in ASD

Dysbiosis: Microbiome signals, epidemiological risk factors and gut symptoms all suggest a link between ASD and the microbiome. ASD is frequently accompanied by severe gastrointestinal manifestations, revealing symptoms more proximal to the activities of the gut microbiome. Moreover, the risk of developing ASD is significantly increased among children born by caesarean section or those exposed to multiple courses of antibiotics early in life. Mouse studies have demonstrated the ability to transfer ASD-like symptoms by transferring stool from humans with ASD. Conversely, certain ASD-mouse models have shown that ASD-like symptoms can be reduced by microbiome transfer from a neurotypical donor.

Mechanism of Action: Once considered a strictly neurological condition, the modern view of ASD has evolved to encompass multiple systems, including interactions between the central nervous system, the enteric nervous system and the gut microbiome, also called the gut-brain axis. Many well-known neuro-active signaling molecules such as gamma-aminobutyric acid, or GABA, serotonin and oxytocin are either produced or modulated by the microbiome, which has led to efforts to better understand the role of the microbiome across a range of behavioral and neurological conditions, including ASD. Current research highlights several pathways in the gut-brain axis that may be key to ASD. Neuro-active metabolites that are exclusively produced by the microbiome, such as 4-ethylphenylsulfate, or 4EPS, are significantly elevated among children with ASD relative to neurotypical controls, and are capable of inducing ASD-like symptoms in mice. Oxytocin, a neuropeptide responsible for regulating social bonding and behavior, has long been a target for drug development in ASD, but exogenous agonism of oxytocin has been challenging due to a short half-life of oxytocin. Certain microbes can induce endogenous production of oxytocin, providing an alternative means to engage this important pathway. Preclinical work has demonstrated that introduction of oxytocin-inducing bacteria can restore neurotypical behavior in three independent ASD murine models. This rescue is dependent on the vagus nerve which connects the enteric nervous system in the gut with the central nervous system and was eliminated when the gene for the oxytocin receptor was knocked out. This pathway-level dysbiosis and previously described community-level dysbiosis suggest the potential role for an Enriched Consortia product strategy.

Third-Party Clinical Data: At least five investigator-sponsored clinical studies have found that the restoration of a healthy microbiome by FMT is associated with marked improvements in behavioral and gastrointestinal symptoms among children with ASD. An open-label proof-of-concept trial administering FMT for 8 weeks reported that, two years after treatment, most participants reported gastrointestinal symptoms remaining improved compared to baseline and 44% of study participants who had previously been diagnosed with ASD fell below the Childhood Autism Rating Scale (CARS) score cut-off used to classify autism. Even using a more stringent CARS score cut-off of 25, we find that 33% of participants no longer meet the diagnostic criteria for ASD, as shown in the below graph. Additionally, in a randomized, controlled trial, children with ASD receiving FMT and behavioral therapy showed a statistically significant improvement in their behavioral symptoms compared to the control group receiving behavioral therapy alone.

21

Behavioral Scores Improved Dramatically Over Two Years in an Open-Label,

Proof-of-Concept FMT Trial

Our Product Candidate: FIN-211

FIN-211 is an orally administered, Enriched Consortia product candidate designed to deliver both a complete microbiome and targeted microbes not found in most healthy donors. Based on our understanding of the biology of ASD, we have identified species capable of inducing oxytocin production and improving gastrointestinal barrier function. We believe these organisms may have important therapeutic benefits for individuals with ASD. These organisms are not ubiquitous in healthy donors, so our Complete Consortia product strategy would not generally include these microbes. Accordingly, we have decided to pursue an Enriched Consortia product strategy that includes both strains targeting oxytocin-production and a complete microbiome to address community-level dysbiosis, which we believe best positions FIN-211 to potentially address both the gastrointestinal and behavioral symptoms of ASD.

Clinical Development of FIN-211 to Address Symptoms of ASD

We are preparing to initiate a Phase 1b clinical trial, which we refer to as AUSPIRE, of FIN-211 in children with ASD (ages 5–17 years) with constipation. Although FIN-211 is not directly addressed in the February 2022 Clinical Hold Letter, it is an Enriched Consortia product candidate that includes donor-derived components. Because the February 2022 Clinical Hold Letter is concerned with SARS-CoV-2 screening measures for donor-derived microbiota material, the clinical hold will delay initiation of AUSPIRE and will require us to conduct additional manufacturing activities (including manufacturing additional components of FIN-211) in order to satisfy the FDA's requests related to SARS-CoV-2 screening and testing. We have submitted a Complete Response to the February 2022 Clinical Hold Letter and we are communicating with the FDA to resolve the clinical hold as soon as possible. We are evaluating the extent of the delay the clinical hold and the related manufacturing activities will have on the expected timing of AUSPIRE; based on manufacturing timelines, we expect at least a one-quarter delay.

Based on clinical FMT data and preclinical data with oxytocin-inducing strains, we believe FIN-211 is positioned to address both the gastrointestinal and behavioral symptoms of ASD. The FDA has indicated that either gastrointestinal or behavioral endpoints could support a biologics license application and we are evaluating both gastrointestinal and behavioral endpoints. Given the absence of FDA-approved therapies and building on our discussions with the FDA, we aim to continue to validate behavioral instruments as part of our clinical development plans. We believe FIN-211 can potentially address adults with ASD as well as both adults and children without gastrointestinal symptoms, expanding beyond our initial population of pediatrics with gastrointestinal symptoms where we expect to observe an enriched signal.

We believe this development strategy represents an attractive entry into the gut-brain axis, providing two opportunities to provide therapeutic benefit to patients with ASD, both for behavioral symptoms and lower-risk gastrointestinal endpoints. Furthermore, we believe that ASD could validate our microbiome-based approach to addressing additional gut-brain axis indications. We plan to leverage existing and emerging clinical data from our academic collaborators to inform the development strategy of future product candidates to address additional neurological disorders that are associated with the gut-brain axis.

22

TAK-524 (Ulcerative Colitis) & FIN-525 (Crohn’s Disease) for the Treatment of Inflammatory Bowel Disease

Overview

TAK-524 (formerly known as FIN-524) and FIN-525 are each orally administered Targeted Consortia product candidates designed for the treatment of ulcerative colitis (TAK-524) and Crohn’s disease (FIN-525). We initially partnered with Takeda, a global leader in inflammatory bowel disease, or IBD, to develop TAK-524. TAK-524 comprises targeted strains identified by our Human-First Discovery platform, which do not require donors. Following the achievement of certain preclinical milestones in the development of TAK-524 for ulcerative colitis, we expanded our development partnership with Takeda to include FIN-525, a program to develop a live biotherapeutic product optimized for Crohn’s disease that also comprises targeted strains identified by our Human-First Discovery platform. In August 2021, Takeda accelerated its leadership role in TAK-524, taking responsibility for clinical development, while we continue to conduct discovery efforts on FIN-525. We believe that the development programs for TAK-524 and FIN-525, which are Targeted Consortia product candidates composed of strains grown from master cell banks, are not affected by the February 2022 Clinical Hold Letter.

Indication Overview

Ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease are the two principal sub-types of IBD. IBD comprises a set of heterogeneous autoimmune conditions that cause inflammation of the gastrointestinal tract. Symptoms of IBD include severe, chronic abdominal pain, diarrhea, gastrointestinal bleeding and weight loss. Patients have substantially higher risk of colon cancer, gastrointestinal perforations and infections, and many eventually require surgical resection of portions of their gastrointestinal tract or colectomy. Patients undergo periods of active disease (flares) accompanied by intermittent periods of little or no disease activity (remission). Over 3 million Americans and 10 million people globally are thought to suffer from IBD, and the incidence has increased rapidly over the past few decades. By some estimates, the total financial burden of care for patients with IBD exceeds $31 billion in the United States annually.

Existing Therapeutics and Their Limitations

The current treatment options vary by disease types and severity, and are designed to reduce inflammation, but do not address the underlying cause of disease. Active mild-to-moderate ulcerative colitis is often treated with 5-ASA agents. However, over 70% of patients fail to enter remission. Active mild-moderate Crohn’s disease have limited therapeutic options. Corticosteroids are commonly used in active disease; however, the long-term side effect profile is poor and includes increased risk of infections, type 2 diabetes, weight gain, mood disturbances and hypertension. Biologic agents that suppress inflammatory cytokines or cell trafficking are not typically orally administered agents, and have poor rates of inducing remission. There is a single, recently approved oral biologic for moderate to severe Crohn’s disease; however, similar to other biologics, it is associated with increased risk for severe infections, blood clots and the development of malignancy. Commonly used anti-TNF biologic agents may lead to serious infections due to immunosuppression, and there have been reports of hepatosplenic T-cell lymphoma, a rare form of lymphoma that is fatal in some patients.

Overall, current treatments for IBD fail to address the underlying causes of inflammation, and there is a significant need for well-tolerated, easily administered, disease-modifying agents in IBD.

Rationale for Microbiome Therapeutics in IBD

Dysbiosis: Over the last decade, a number of lines of evidence have pointed to the promise of microbiome therapeutics in treating ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease. Inflammatory bowel disease is one of the suite of chronic inflammatory diseases that has risen dramatically in prevalence in developed nations marked by gastrointestinal dysbiosis.

Mechanism of Action: Extensive preclinical work has demonstrated the criticality of the microbiome, including specific microbial metabolites, in regulating gastrointestinal tract inflammation, predicting response to therapy and determining the risk of disease recurrence after surgery. The improvement of gut barrier integrity, reduction of local immune activation and modulation of gut inflammation are all modulated by the microbiome.

Third-Party Clinical Data: FMT studies in IBD were key in our decision to develop Targeted Consortia product candidates for ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease. Data from over 40 FMT studies, including five randomized, placebo-controlled trials in ulcerative colitis and one randomized, placebo-controlled trial in Crohn’s disease, have shown promising clinical outcomes. Some of these interventional studies also served as our main discovery datasets to select which strains and functions to include in our Targeted Consortia approach for IBD. Clinical studies with only spore-forming compositions have

23

yielded mixed results, highlighting the value of our approach, which leverages both spore-forming and non-spore forming compositions.

TAK-524 and FIN-525

TAK-524 is a Targeted Consortia product candidate of nine bacterial strains selected for the treatment of ulcerative colitis, and is orally administered in a lyophilized formulation. We designed this consortium to target three specific modes of action: two classes of immunoregulatory metabolites, each targeting a different set of host pathways, and donor strains linked to remission following FMT in patients with ulcerative colitis. Takeda now leads development of TAK-524.

FIN-525 is a discovery-stage program designing a Targeted Consortia product candidate for the treatment of Crohn’s disease. The strategy for this consortium, which is differentiated from ulcerative colitis, includes donor strains depleted in Crohn’s patients and linked to remission following FMT in these patients, as well as several classes of metabolites, each targeting a different set of host pathways.

TAK-524 and FIN-525 leverage data collected from over two dozen cohorts comprising over 2,300 patients, including six FMT studies in ulcerative colitis and five in Crohn’s disease. Our machine learning platform identified microbes and microbial functions deficient in patients with ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease compared to non-IBD controls. We tested these hypotheses with FMT data to identify the subset most likely to be causal, focusing on organisms consistently shown to be enriched among successful FMTs and subjects without IBD. To reduce the translational risk of these empirical signals, we isolated target organisms directly from specific donor samples that induced remission in clinical studies of FMT in IBD. In vitro and in vivo measurements on the isolated strains and consortia then confirmed the signals of biological activity hypothesized by our machine learning platform. We are currently conducting discovery efforts on FIN-525.

Remission Rates in Active Ulcerative Colitis among Four Placebo-Controlled FMT Trials and a TNF Biologic Trial |

Platform Used to Identify “Super Donor” Strains as Potential Therapeutic Candidates |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Selecting a strain associated with positive FMT outcomes starts with machine learning models of clinical data. For TAK-524, an analysis of data from over 1000 patients was used to quantify the relationship between each clade of bacteria (each represented as a dot) and ulcerative colitis. On the x-axis, the degree to which each clade is depleted from a patient’s microbiome relative to healthy controls is shown. On the y-axis, the impact of each clade in driving remission when added to a patient’s microbiome by FMT is shown. Colors indicate the higher-level phylogenetic group each dot is assigned to. The bacterial clades with the greatest effect (top right quadrant) are the targets we isolated for in-vitro validation. |

|

Our Collaborations and License Agreements

Takeda Collaboration

In January 2017, we entered into an agreement, or the Takeda Agreement, with Takeda, pursuant to which we granted Takeda a worldwide, exclusive license, with the right to grant sublicenses, under our rights in certain patents, patent applications and know-how to develop, have developed, manufacture, have manufactured, make, have made, use, have used, offer for sale, sell, have sold, commercialize, have commercialized and import our microbiome therapeutic candidate TAK-524 for the prevention, diagnosis, theragnosis or treatment of diseases in humans. We subsequently amended and restated the Takeda Agreement in October 2019 to provide a worldwide, exclusive license to a second microbiome therapeutic candidate, FIN-525. We further amended the Takeda Agreement in August 2021 to transition primary responsibility for further development and manufacturing activities of TAK-524 to Takeda in accordance with a transition plan, and Takeda assumed sole responsibility for regulatory matters with respect to TAK-524. In November 2021, we further amended the Takeda Agreement to enable us to carry out certain FIN-525 preliminary evaluation activities.

24

Under the terms of the Takeda Agreement, we agreed to design TAK-524 (a product candidate optimized for ulcerative colitis) for Takeda based on selection criteria within a product-specific development plan. We also agreed to conduct feasibility studies on FIN-525 (a program to develop a live biotherapeutic product optimized for Crohn’s disease) for Takeda, and Takeda can determine whether to initiate a full product-specific development plan for FIN-525 following its review of the data from our feasibility studies. The FIN-525 feasibility study was completed in March 2021. Takeda is to select one optimal microbial cocktail for each of TAK-524 and FIN-525 after completion of certain initial product development activities. Thereafter, prior to initiation of the first Phase 3 clinical trial for TAK-524 or FIN-525, as applicable, Takeda has the right to substitute the initially selected microbial cocktail for another microbial cocktail selected by Takeda from certain alternative cocktails that were designated by Takeda at the time of selecting the initial microbial cocktail.

Pursuant to the Takeda Agreement, we are primarily responsible for early-stage development activities for FIN-525 pursuant to an agreed upon development plan and budget, including potentially through Phase 2 clinical trials, subject to Takeda’s right to either co-develop a product with us at Phase 2 or assume responsibility for such development. After the successful completion of the first Phase 2 clinical trial for FIN-525, Takeda will assume primary responsibility for the Phase 3 clinical program. Initially, we are responsible for clinical supply of FIN-525; however, Takeda is required to assume responsibility for such manufacture and supply no later than six months after completion of the first Phase 2 clinical trial for the first FIN-525 product candidate. All such development and manufacturing activities will be overseen by certain joint committees. Pursuant to the August 2021 amendment to the Takeda Agreement, Takeda assumed primary responsibility for early-stage development and manufacturing activities with respect to TAK-524. Takeda also assumed sole responsibility for regulatory matters with respect to TAK-524. We remain responsible for certain development activities designated in the TAK-524 development plan, for which we will continue to receive reimbursement from Takeda.

Takeda is responsible for up to 110% of our budgeted full-time equivalent costs in connection with our development activities for TAK-524 (and FIN-525, if Takeda elects to initiate a full development plan for FIN-525) as well as all costs related to chemistry, manufacturing and control development or other development costs incurred after the initial selection of an optimal microbial cocktail. Takeda is solely responsible for all commercial activities related to the TAK-524 and FIN-525 product candidates, at its cost.