Clinical development

We are currently conducting multiple clinical trials of

AGTC-501

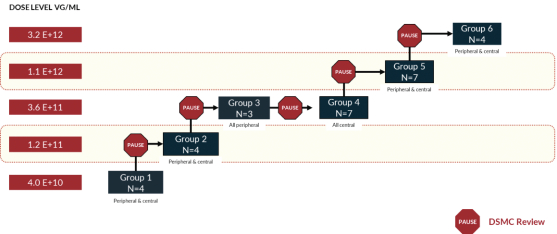

that are intended to support the potential submission of a Biologics License Application (“BLA”), including a Phase 1/2 trial, or Horizon, which incorporates an expansion portion that we refer to as the Skyline trial. Horizon is a dose escalation trial at multiple clinical sites in the U.S. that specialize in treating patients with inherited retinal diseases. Horizon includes five dose levels, spanning a range of approximately

80-fold,

that are intended to provide us with robust safety and biologic activity data with which to inform the next stages of clinical development. The primary endpoint of the trial is safety, and data released through 24 months after treatment have shown AGTC-501

continues to demonstrate a favorable safety profile and is well tolerated by patients dosed both centrally and peripherally. No serious adverse events related to AGTC-501

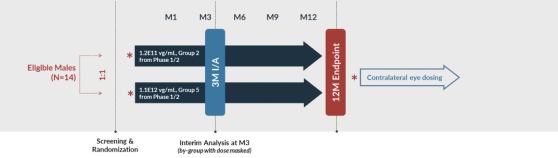

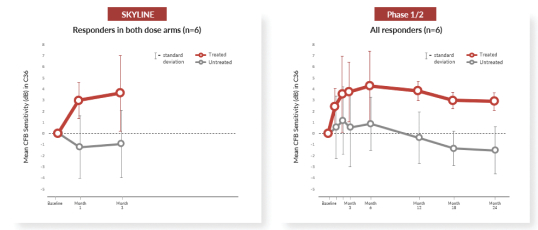

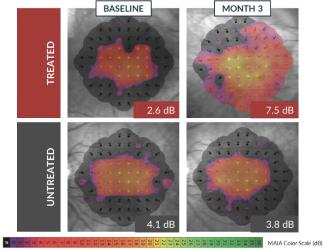

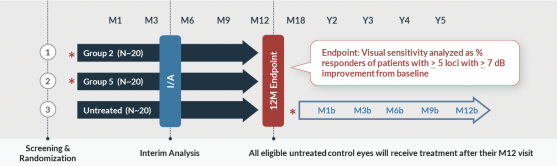

have been reported through month 24. In addition to safety, Horizon is evaluating biologic activity by assessing changes in several measures of visual function. There were clinically meaningful improvements in visual sensitivity, as measured by microperimetry, that continued through 24 months after treatment in centrally treated patients. Specifically, a clinically significant treatment effect in visual sensitivity was seen and sustained 24 months after treatment when comparing treated eyes to fellow untreated eyes in this trial, and improvements in visual sensitivity continue to correlate with improvements in retinal structure 24 months after treatment. In addition, improvements in best corrected visual acuity seen 12 months after treatment continue to show evidence of a biological response 24 months after treatment. Collectively, these clinical data are encouraging and continue to inform our clinical development in patients with XLRP. XLRP Horizon Trial Design and Dosing Schedule

Boxed/shaded groups are dose groups moving forward to Skyline and Vista trials. N=29 for all patients dosed and N=20 for centrally dosed patients.

7