00010647282021FYfalsehttp://fasb.org/us-gaap/2021-01-31#AccountsPayableAndAccruedLiabilitiesCurrenthttp://fasb.org/us-gaap/2021-01-31#AccountsPayableAndAccruedLiabilitiesCurrenthttp://fasb.org/us-gaap/2021-01-31#LongTermDebtAndCapitalLeaseObligationshttp://fasb.org/us-gaap/2021-01-31#LongTermDebtAndCapitalLeaseObligations00010647282021-01-012021-12-3100010647282021-06-30iso4217:USD00010647282022-02-11xbrli:shares0001064728btu:AtMarketIssuanceMember2021-01-012021-12-310001064728us-gaap:CommonStockMemberbtu:AtMarketIssuanceMember2021-01-012021-12-310001064728btu:DebtForEquityExchangeMember2021-12-310001064728btu:A6.000SeniorSecuredNotesDue2022Memberbtu:DebtForEquityExchangeMemberus-gaap:SeniorNotesMember2021-01-012021-12-310001064728btu:DebtForEquityExchangeMemberus-gaap:SeniorNotesMemberbtu:A6.375SeniorSecuredNotesDue2025Member2021-01-012021-12-310001064728btu:DebtForEquityExchangeMemberus-gaap:SeniorNotesMemberbtu:A8500SeniorSecuredNotesDue2024Member2021-01-012021-12-3100010647282020-01-012020-12-3100010647282019-01-012019-12-31iso4217:USDxbrli:shares00010647282021-12-3100010647282020-12-310001064728us-gaap:PreferredStockMember2021-12-310001064728us-gaap:PreferredStockMember2020-12-310001064728btu:SeriesCommonStockMember2020-12-310001064728btu:SeriesCommonStockMember2021-12-310001064728us-gaap:CommonStockMember2021-12-310001064728us-gaap:CommonStockMember2020-12-3100010647282019-12-3100010647282018-12-310001064728us-gaap:CommonStockMember2018-12-310001064728us-gaap:AdditionalPaidInCapitalMember2018-12-310001064728us-gaap:TreasuryStockMember2018-12-310001064728us-gaap:RetainedEarningsMember2018-12-310001064728us-gaap:AccumulatedOtherComprehensiveIncomeMember2018-12-310001064728us-gaap:NoncontrollingInterestMember2018-12-310001064728us-gaap:RetainedEarningsMember2019-01-012019-12-310001064728us-gaap:NoncontrollingInterestMember2019-01-012019-12-310001064728us-gaap:AdditionalPaidInCapitalMember2019-01-012019-12-310001064728us-gaap:AccumulatedOtherComprehensiveIncomeMember2019-01-012019-12-310001064728us-gaap:TreasuryStockMember2019-01-012019-12-310001064728us-gaap:CommonStockMember2019-12-310001064728us-gaap:AdditionalPaidInCapitalMember2019-12-310001064728us-gaap:TreasuryStockMember2019-12-310001064728us-gaap:RetainedEarningsMember2019-12-310001064728us-gaap:AccumulatedOtherComprehensiveIncomeMember2019-12-310001064728us-gaap:NoncontrollingInterestMember2019-12-310001064728us-gaap:RetainedEarningsMember2020-01-012020-12-310001064728us-gaap:NoncontrollingInterestMember2020-01-012020-12-310001064728us-gaap:AccumulatedOtherComprehensiveIncomeMember2020-01-012020-12-310001064728us-gaap:AdditionalPaidInCapitalMember2020-01-012020-12-310001064728us-gaap:TreasuryStockMember2020-01-012020-12-310001064728us-gaap:CommonStockMember2020-12-310001064728us-gaap:AdditionalPaidInCapitalMember2020-12-310001064728us-gaap:TreasuryStockMember2020-12-310001064728us-gaap:RetainedEarningsMember2020-12-310001064728us-gaap:AccumulatedOtherComprehensiveIncomeMember2020-12-310001064728us-gaap:NoncontrollingInterestMember2020-12-310001064728us-gaap:RetainedEarningsMember2021-01-012021-12-310001064728us-gaap:NoncontrollingInterestMember2021-01-012021-12-310001064728us-gaap:AccumulatedOtherComprehensiveIncomeMember2021-01-012021-12-310001064728us-gaap:AdditionalPaidInCapitalMember2021-01-012021-12-310001064728us-gaap:CommonStockMember2021-01-012021-12-310001064728us-gaap:CommonStockMemberus-gaap:CommonStockMember2021-01-012021-12-310001064728us-gaap:AdditionalPaidInCapitalMemberus-gaap:CommonStockMember2021-01-012021-12-310001064728us-gaap:CommonStockMember2021-01-012021-12-310001064728us-gaap:TreasuryStockMember2021-01-012021-12-310001064728us-gaap:CommonStockMember2021-12-310001064728us-gaap:AdditionalPaidInCapitalMember2021-12-310001064728us-gaap:TreasuryStockMember2021-12-310001064728us-gaap:RetainedEarningsMember2021-12-310001064728us-gaap:AccumulatedOtherComprehensiveIncomeMember2021-12-310001064728us-gaap:NoncontrollingInterestMember2021-12-310001064728srt:MaximumMemberus-gaap:BuildingAndBuildingImprovementsMember2021-01-012021-12-310001064728srt:MinimumMemberus-gaap:MachineryAndEquipmentMember2021-01-012021-12-310001064728srt:MaximumMemberus-gaap:MachineryAndEquipmentMember2021-01-012021-12-31xbrli:pure0001064728btu:MiddlemountMineMember2021-12-310001064728btu:ThermalCoalMemberbtu:SeaborneThermalMiningMemberus-gaap:DomesticDestinationMember2021-01-012021-12-310001064728btu:ThermalCoalMemberbtu:SeaborneMetallurgicalMiningMemberus-gaap:DomesticDestinationMember2021-01-012021-12-310001064728btu:ThermalCoalMemberbtu:PowderRiverBasinMiningMemberus-gaap:DomesticDestinationMember2021-01-012021-12-310001064728btu:ThermalCoalMemberus-gaap:DomesticDestinationMemberbtu:OtherUSThermalMiningMember2021-01-012021-12-310001064728btu:ThermalCoalMemberus-gaap:DomesticDestinationMemberus-gaap:CorporateAndOtherMember2021-01-012021-12-310001064728btu:ThermalCoalMemberus-gaap:DomesticDestinationMember2021-01-012021-12-310001064728btu:ThermalCoalMemberbtu:SeaborneThermalMiningMemberus-gaap:GeographicDistributionForeignMember2021-01-012021-12-310001064728btu:ThermalCoalMemberbtu:SeaborneMetallurgicalMiningMemberus-gaap:GeographicDistributionForeignMember2021-01-012021-12-310001064728btu:ThermalCoalMemberbtu:PowderRiverBasinMiningMemberus-gaap:GeographicDistributionForeignMember2021-01-012021-12-310001064728btu:ThermalCoalMemberbtu:OtherUSThermalMiningMemberus-gaap:GeographicDistributionForeignMember2021-01-012021-12-310001064728btu:ThermalCoalMemberus-gaap:CorporateAndOtherMemberus-gaap:GeographicDistributionForeignMember2021-01-012021-12-310001064728btu:ThermalCoalMemberus-gaap:GeographicDistributionForeignMember2021-01-012021-12-310001064728btu:ThermalCoalMemberbtu:SeaborneThermalMiningMember2021-01-012021-12-310001064728btu:ThermalCoalMemberbtu:SeaborneMetallurgicalMiningMember2021-01-012021-12-310001064728btu:ThermalCoalMemberbtu:PowderRiverBasinMiningMember2021-01-012021-12-310001064728btu:ThermalCoalMemberbtu:OtherUSThermalMiningMember2021-01-012021-12-310001064728btu:ThermalCoalMemberus-gaap:CorporateAndOtherMember2021-01-012021-12-310001064728btu:ThermalCoalMember2021-01-012021-12-310001064728btu:SeaborneThermalMiningMemberbtu:MetallurgicalCoalMemberus-gaap:GeographicDistributionForeignMember2021-01-012021-12-310001064728btu:SeaborneMetallurgicalMiningMemberbtu:MetallurgicalCoalMemberus-gaap:GeographicDistributionForeignMember2021-01-012021-12-310001064728btu:PowderRiverBasinMiningMemberbtu:MetallurgicalCoalMemberus-gaap:GeographicDistributionForeignMember2021-01-012021-12-310001064728btu:MetallurgicalCoalMemberbtu:OtherUSThermalMiningMemberus-gaap:GeographicDistributionForeignMember2021-01-012021-12-310001064728btu:MetallurgicalCoalMemberus-gaap:CorporateAndOtherMemberus-gaap:GeographicDistributionForeignMember2021-01-012021-12-310001064728btu:MetallurgicalCoalMemberus-gaap:GeographicDistributionForeignMember2021-01-012021-12-310001064728btu:SeaborneThermalMiningMemberbtu:MetallurgicalCoalMember2021-01-012021-12-310001064728btu:SeaborneMetallurgicalMiningMemberbtu:MetallurgicalCoalMember2021-01-012021-12-310001064728btu:PowderRiverBasinMiningMemberbtu:MetallurgicalCoalMember2021-01-012021-12-310001064728btu:MetallurgicalCoalMemberbtu:OtherUSThermalMiningMember2021-01-012021-12-310001064728btu:MetallurgicalCoalMemberus-gaap:CorporateAndOtherMember2021-01-012021-12-310001064728btu:MetallurgicalCoalMember2021-01-012021-12-310001064728btu:SeaborneThermalMiningMemberus-gaap:ProductAndServiceOtherMember2021-01-012021-12-310001064728btu:SeaborneMetallurgicalMiningMemberus-gaap:ProductAndServiceOtherMember2021-01-012021-12-310001064728btu:PowderRiverBasinMiningMemberus-gaap:ProductAndServiceOtherMember2021-01-012021-12-310001064728btu:OtherUSThermalMiningMemberus-gaap:ProductAndServiceOtherMember2021-01-012021-12-310001064728us-gaap:CorporateAndOtherMemberus-gaap:ProductAndServiceOtherMember2021-01-012021-12-310001064728us-gaap:ProductAndServiceOtherMember2021-01-012021-12-310001064728btu:SeaborneThermalMiningMember2021-01-012021-12-310001064728btu:SeaborneMetallurgicalMiningMember2021-01-012021-12-310001064728btu:PowderRiverBasinMiningMember2021-01-012021-12-310001064728btu:OtherUSThermalMiningMember2021-01-012021-12-310001064728us-gaap:CorporateAndOtherMember2021-01-012021-12-310001064728btu:ThermalCoalMemberbtu:SeaborneThermalMiningMemberus-gaap:DomesticDestinationMember2020-01-012020-12-310001064728btu:ThermalCoalMemberbtu:SeaborneMetallurgicalMiningMemberus-gaap:DomesticDestinationMember2020-01-012020-12-310001064728btu:ThermalCoalMemberbtu:PowderRiverBasinMiningMemberus-gaap:DomesticDestinationMember2020-01-012020-12-310001064728btu:ThermalCoalMemberus-gaap:DomesticDestinationMemberbtu:OtherUSThermalMiningMember2020-01-012020-12-310001064728btu:ThermalCoalMemberus-gaap:DomesticDestinationMemberus-gaap:CorporateAndOtherMember2020-01-012020-12-310001064728btu:ThermalCoalMemberus-gaap:DomesticDestinationMember2020-01-012020-12-310001064728btu:ThermalCoalMemberbtu:SeaborneThermalMiningMemberus-gaap:GeographicDistributionForeignMember2020-01-012020-12-310001064728btu:ThermalCoalMemberbtu:SeaborneMetallurgicalMiningMemberus-gaap:GeographicDistributionForeignMember2020-01-012020-12-310001064728btu:ThermalCoalMemberbtu:PowderRiverBasinMiningMemberus-gaap:GeographicDistributionForeignMember2020-01-012020-12-310001064728btu:ThermalCoalMemberbtu:OtherUSThermalMiningMemberus-gaap:GeographicDistributionForeignMember2020-01-012020-12-310001064728btu:ThermalCoalMemberus-gaap:CorporateAndOtherMemberus-gaap:GeographicDistributionForeignMember2020-01-012020-12-310001064728btu:ThermalCoalMemberus-gaap:GeographicDistributionForeignMember2020-01-012020-12-310001064728btu:ThermalCoalMemberbtu:SeaborneThermalMiningMember2020-01-012020-12-310001064728btu:ThermalCoalMemberbtu:SeaborneMetallurgicalMiningMember2020-01-012020-12-310001064728btu:ThermalCoalMemberbtu:PowderRiverBasinMiningMember2020-01-012020-12-310001064728btu:ThermalCoalMemberbtu:OtherUSThermalMiningMember2020-01-012020-12-310001064728btu:ThermalCoalMemberus-gaap:CorporateAndOtherMember2020-01-012020-12-310001064728btu:ThermalCoalMember2020-01-012020-12-310001064728btu:SeaborneThermalMiningMemberbtu:MetallurgicalCoalMemberus-gaap:GeographicDistributionForeignMember2020-01-012020-12-310001064728btu:SeaborneMetallurgicalMiningMemberbtu:MetallurgicalCoalMemberus-gaap:GeographicDistributionForeignMember2020-01-012020-12-310001064728btu:PowderRiverBasinMiningMemberbtu:MetallurgicalCoalMemberus-gaap:GeographicDistributionForeignMember2020-01-012020-12-310001064728btu:MetallurgicalCoalMemberbtu:OtherUSThermalMiningMemberus-gaap:GeographicDistributionForeignMember2020-01-012020-12-310001064728btu:MetallurgicalCoalMemberus-gaap:CorporateAndOtherMemberus-gaap:GeographicDistributionForeignMember2020-01-012020-12-310001064728btu:MetallurgicalCoalMemberus-gaap:GeographicDistributionForeignMember2020-01-012020-12-310001064728btu:SeaborneThermalMiningMemberbtu:MetallurgicalCoalMember2020-01-012020-12-310001064728btu:SeaborneMetallurgicalMiningMemberbtu:MetallurgicalCoalMember2020-01-012020-12-310001064728btu:PowderRiverBasinMiningMemberbtu:MetallurgicalCoalMember2020-01-012020-12-310001064728btu:MetallurgicalCoalMemberbtu:OtherUSThermalMiningMember2020-01-012020-12-310001064728btu:MetallurgicalCoalMemberus-gaap:CorporateAndOtherMember2020-01-012020-12-310001064728btu:MetallurgicalCoalMember2020-01-012020-12-310001064728btu:SeaborneThermalMiningMemberus-gaap:ProductAndServiceOtherMember2020-01-012020-12-310001064728btu:SeaborneMetallurgicalMiningMemberus-gaap:ProductAndServiceOtherMember2020-01-012020-12-310001064728btu:PowderRiverBasinMiningMemberus-gaap:ProductAndServiceOtherMember2020-01-012020-12-310001064728btu:OtherUSThermalMiningMemberus-gaap:ProductAndServiceOtherMember2020-01-012020-12-310001064728us-gaap:CorporateAndOtherMemberus-gaap:ProductAndServiceOtherMember2020-01-012020-12-310001064728us-gaap:ProductAndServiceOtherMember2020-01-012020-12-310001064728btu:SeaborneThermalMiningMember2020-01-012020-12-310001064728btu:SeaborneMetallurgicalMiningMember2020-01-012020-12-310001064728btu:PowderRiverBasinMiningMember2020-01-012020-12-310001064728btu:OtherUSThermalMiningMember2020-01-012020-12-310001064728us-gaap:CorporateAndOtherMember2020-01-012020-12-310001064728btu:ThermalCoalMemberbtu:SeaborneThermalMiningMemberus-gaap:DomesticDestinationMember2019-01-012019-12-310001064728btu:ThermalCoalMemberbtu:SeaborneMetallurgicalMiningMemberus-gaap:DomesticDestinationMember2019-01-012019-12-310001064728btu:ThermalCoalMemberbtu:PowderRiverBasinMiningMemberus-gaap:DomesticDestinationMember2019-01-012019-12-310001064728btu:ThermalCoalMemberus-gaap:DomesticDestinationMemberbtu:OtherUSThermalMiningMember2019-01-012019-12-310001064728btu:ThermalCoalMemberus-gaap:DomesticDestinationMemberus-gaap:CorporateAndOtherMember2019-01-012019-12-310001064728btu:ThermalCoalMemberus-gaap:DomesticDestinationMember2019-01-012019-12-310001064728btu:ThermalCoalMemberbtu:SeaborneThermalMiningMemberus-gaap:GeographicDistributionForeignMember2019-01-012019-12-310001064728btu:ThermalCoalMemberbtu:SeaborneMetallurgicalMiningMemberus-gaap:GeographicDistributionForeignMember2019-01-012019-12-310001064728btu:ThermalCoalMemberbtu:PowderRiverBasinMiningMemberus-gaap:GeographicDistributionForeignMember2019-01-012019-12-310001064728btu:ThermalCoalMemberbtu:OtherUSThermalMiningMemberus-gaap:GeographicDistributionForeignMember2019-01-012019-12-310001064728btu:ThermalCoalMemberus-gaap:CorporateAndOtherMemberus-gaap:GeographicDistributionForeignMember2019-01-012019-12-310001064728btu:ThermalCoalMemberus-gaap:GeographicDistributionForeignMember2019-01-012019-12-310001064728btu:ThermalCoalMemberbtu:SeaborneThermalMiningMember2019-01-012019-12-310001064728btu:ThermalCoalMemberbtu:SeaborneMetallurgicalMiningMember2019-01-012019-12-310001064728btu:ThermalCoalMemberbtu:PowderRiverBasinMiningMember2019-01-012019-12-310001064728btu:ThermalCoalMemberbtu:OtherUSThermalMiningMember2019-01-012019-12-310001064728btu:ThermalCoalMemberus-gaap:CorporateAndOtherMember2019-01-012019-12-310001064728btu:ThermalCoalMember2019-01-012019-12-310001064728btu:SeaborneThermalMiningMemberbtu:MetallurgicalCoalMemberus-gaap:GeographicDistributionForeignMember2019-01-012019-12-310001064728btu:SeaborneMetallurgicalMiningMemberbtu:MetallurgicalCoalMemberus-gaap:GeographicDistributionForeignMember2019-01-012019-12-310001064728btu:PowderRiverBasinMiningMemberbtu:MetallurgicalCoalMemberus-gaap:GeographicDistributionForeignMember2019-01-012019-12-310001064728btu:MetallurgicalCoalMemberbtu:OtherUSThermalMiningMemberus-gaap:GeographicDistributionForeignMember2019-01-012019-12-310001064728btu:MetallurgicalCoalMemberus-gaap:CorporateAndOtherMemberus-gaap:GeographicDistributionForeignMember2019-01-012019-12-310001064728btu:MetallurgicalCoalMemberus-gaap:GeographicDistributionForeignMember2019-01-012019-12-310001064728btu:SeaborneThermalMiningMemberbtu:MetallurgicalCoalMember2019-01-012019-12-310001064728btu:SeaborneMetallurgicalMiningMemberbtu:MetallurgicalCoalMember2019-01-012019-12-310001064728btu:PowderRiverBasinMiningMemberbtu:MetallurgicalCoalMember2019-01-012019-12-310001064728btu:MetallurgicalCoalMemberbtu:OtherUSThermalMiningMember2019-01-012019-12-310001064728btu:MetallurgicalCoalMemberus-gaap:CorporateAndOtherMember2019-01-012019-12-310001064728btu:MetallurgicalCoalMember2019-01-012019-12-310001064728btu:SeaborneThermalMiningMemberus-gaap:ProductAndServiceOtherMember2019-01-012019-12-310001064728btu:SeaborneMetallurgicalMiningMemberus-gaap:ProductAndServiceOtherMember2019-01-012019-12-310001064728btu:PowderRiverBasinMiningMemberus-gaap:ProductAndServiceOtherMember2019-01-012019-12-310001064728btu:OtherUSThermalMiningMemberus-gaap:ProductAndServiceOtherMember2019-01-012019-12-310001064728us-gaap:CorporateAndOtherMemberus-gaap:ProductAndServiceOtherMember2019-01-012019-12-310001064728us-gaap:ProductAndServiceOtherMember2019-01-012019-12-310001064728btu:SeaborneThermalMiningMember2019-01-012019-12-310001064728btu:SeaborneMetallurgicalMiningMember2019-01-012019-12-310001064728btu:PowderRiverBasinMiningMember2019-01-012019-12-310001064728btu:OtherUSThermalMiningMember2019-01-012019-12-310001064728us-gaap:CorporateAndOtherMember2019-01-012019-12-310001064728btu:CoalContractAndPhysicalCommodityPurchaseSaleContractsMemberus-gaap:DesignatedAsHedgingInstrumentMember2021-01-012021-12-310001064728btu:CoalContractAndPhysicalCommodityPurchaseSaleContractsMemberus-gaap:DesignatedAsHedgingInstrumentMember2020-01-012020-12-310001064728btu:CoalContractAndPhysicalCommodityPurchaseSaleContractsMemberus-gaap:DesignatedAsHedgingInstrumentMember2019-01-012019-12-310001064728us-gaap:CorporateAndOtherMemberbtu:TradingAndBrokerageCoalDeliveriesMember2021-01-012021-12-310001064728us-gaap:CorporateAndOtherMemberbtu:TradingAndBrokerageCoalDeliveriesMember2020-01-012020-12-310001064728us-gaap:CorporateAndOtherMemberbtu:TradingAndBrokerageCoalDeliveriesMember2019-01-012019-12-310001064728us-gaap:PublicUtilitiesInventoryCoalMember2021-01-012021-12-310001064728us-gaap:PublicUtilitiesInventoryCoalMember2020-01-012020-12-310001064728us-gaap:PublicUtilitiesInventoryCoalMember2019-01-012019-12-3100010647282021-01-012021-12-310001064728us-gaap:TradeAccountsReceivableMember2021-12-310001064728us-gaap:TradeAccountsReceivableMember2020-12-3100010647282015-10-09btu:buyer0001064728btu:BlackLungOccupationalDiseaseLiabilityMemberus-gaap:DisposalGroupDisposedOfByMeansOtherThanSaleNotDiscontinuedOperationsSpinoffMemberbtu:PatriotCoalCorporationMember2008-12-310001064728btu:BlackLungOccupationalDiseaseLiabilityMemberus-gaap:DisposalGroupDisposedOfByMeansOtherThanSaleNotDiscontinuedOperationsSpinoffMemberbtu:PatriotCoalCorporationMember2021-12-310001064728btu:BlackLungOccupationalDiseaseLiabilityMemberus-gaap:DisposalGroupDisposedOfByMeansOtherThanSaleNotDiscontinuedOperationsSpinoffMemberbtu:PatriotCoalCorporationMember2020-12-310001064728btu:BlackLungOccupationalDiseaseLiabilityMemberus-gaap:DisposalGroupDisposedOfByMeansOtherThanSaleNotDiscontinuedOperationsSpinoffMemberbtu:PatriotCoalCorporationMember2021-01-012021-12-310001064728btu:BlackLungOccupationalDiseaseLiabilityMemberus-gaap:DisposalGroupDisposedOfByMeansOtherThanSaleNotDiscontinuedOperationsSpinoffMemberbtu:PatriotCoalCorporationMember2020-01-012020-12-310001064728btu:BlackLungOccupationalDiseaseLiabilityMemberus-gaap:DisposalGroupDisposedOfByMeansOtherThanSaleNotDiscontinuedOperationsSpinoffMemberbtu:PatriotCoalCorporationMember2019-01-012019-12-310001064728btu:MaterialAndSuppliesMember2021-12-310001064728btu:MaterialAndSuppliesMember2020-12-310001064728btu:MiddlemountMineMember2020-12-310001064728btu:MiddlemountMineMember2021-01-012021-12-310001064728btu:MiddlemountMineMember2020-01-012020-12-310001064728btu:MiddlemountMineMember2019-01-012019-12-310001064728btu:OtherEquityMethodInvestmentsMember2021-12-310001064728btu:OtherEquityMethodInvestmentsMember2020-12-310001064728btu:OtherEquityMethodInvestmentsMember2021-01-012021-12-310001064728btu:OtherEquityMethodInvestmentsMember2020-01-012020-12-310001064728btu:OtherEquityMethodInvestmentsMember2019-01-012019-12-310001064728btu:MiddlemountMineMember2021-01-012021-12-310001064728btu:MiddlemountMineMember2019-01-012019-12-310001064728btu:MiddlemountMineMember2020-01-012020-12-310001064728btu:MiddlemountMineMember2021-12-31iso4217:AUD0001064728btu:MiddlemountMineMember2020-12-310001064728btu:MiddlemountMineMember2021-01-012021-12-310001064728btu:DieselFuelHedgeContractsMember2021-12-310001064728us-gaap:ForeignExchangeContractMember2021-12-310001064728srt:ScenarioForecastMembersrt:MinimumMemberus-gaap:ForeignExchangeContractMember2022-09-30iso4217:USDiso4217:AUD0001064728srt:ScenarioForecastMembersrt:MaximumMemberus-gaap:ForeignExchangeContractMember2022-09-300001064728us-gaap:CoalContractMember2021-01-012021-12-31utr:t0001064728srt:ScenarioForecastMemberus-gaap:CoalContractMember2022-01-012022-12-310001064728srt:ScenarioForecastMemberbtu:CoalContractToSettleIn2022Member2022-01-012022-12-310001064728srt:ScenarioForecastMemberbtu:CoalContractToSettleIn2023Member2023-01-012023-12-310001064728srt:ScenarioForecastMember2022-12-310001064728srt:ScenarioForecastMemberus-gaap:CoalContractMember2022-01-012022-03-310001064728btu:PhysicalCommodityPurchaseSaleContractsMemberus-gaap:DesignatedAsHedgingInstrumentMember2021-01-012021-12-310001064728us-gaap:GainLossOnDerivativeInstrumentsMemberus-gaap:DesignatedAsHedgingInstrumentMember2021-10-012021-12-310001064728us-gaap:ForwardContractsMemberus-gaap:DesignatedAsHedgingInstrumentMember2021-10-012021-12-310001064728btu:PhysicalCommodityPurchaseSaleContractsMemberus-gaap:DesignatedAsHedgingInstrumentMember2020-01-012020-12-310001064728us-gaap:GainLossOnDerivativeInstrumentsMemberus-gaap:DesignatedAsHedgingInstrumentMember2020-10-012020-12-310001064728us-gaap:ForwardContractsMemberus-gaap:DesignatedAsHedgingInstrumentMember2020-10-012020-12-310001064728btu:PhysicalCommodityPurchaseSaleContractsMemberus-gaap:DesignatedAsHedgingInstrumentMember2019-01-012019-12-310001064728us-gaap:GainLossOnDerivativeInstrumentsMemberus-gaap:DesignatedAsHedgingInstrumentMember2019-10-012019-12-310001064728us-gaap:ForeignExchangeContractMemberus-gaap:DesignatedAsHedgingInstrumentMember2021-12-310001064728us-gaap:ForeignExchangeContractMemberus-gaap:DesignatedAsHedgingInstrumentMember2020-12-310001064728btu:PhysicalCommodityPurchaseSaleContractsMemberus-gaap:DesignatedAsHedgingInstrumentMember2021-12-310001064728btu:PhysicalCommodityPurchaseSaleContractsMemberus-gaap:DesignatedAsHedgingInstrumentMember2020-12-310001064728us-gaap:DesignatedAsHedgingInstrumentMemberus-gaap:CoalContractMember2021-12-310001064728us-gaap:DesignatedAsHedgingInstrumentMemberus-gaap:CoalContractMember2020-12-310001064728us-gaap:DesignatedAsHedgingInstrumentMember2021-12-310001064728us-gaap:DesignatedAsHedgingInstrumentMember2020-12-310001064728btu:NetAmountMemberus-gaap:DesignatedAsHedgingInstrumentMember2021-12-310001064728btu:CoalTradingMember2021-12-310001064728btu:NetAmountMemberus-gaap:DesignatedAsHedgingInstrumentMember2020-12-310001064728btu:CoalTradingMember2020-12-310001064728us-gaap:ForeignExchangeContractMemberus-gaap:DesignatedAsHedgingInstrumentMember2021-01-012021-12-310001064728us-gaap:DesignatedAsHedgingInstrumentMemberus-gaap:CoalContractMember2021-01-012021-12-310001064728us-gaap:DesignatedAsHedgingInstrumentMember2021-01-012021-12-310001064728us-gaap:ForeignExchangeContractMemberus-gaap:DesignatedAsHedgingInstrumentMember2020-01-012020-12-310001064728us-gaap:DesignatedAsHedgingInstrumentMemberus-gaap:CoalContractMember2020-01-012020-12-310001064728us-gaap:DesignatedAsHedgingInstrumentMember2020-01-012020-12-310001064728us-gaap:ForeignExchangeContractMemberus-gaap:DesignatedAsHedgingInstrumentMember2019-01-012019-12-310001064728us-gaap:DesignatedAsHedgingInstrumentMemberus-gaap:CoalContractMember2019-01-012019-12-310001064728us-gaap:DesignatedAsHedgingInstrumentMember2019-01-012019-12-310001064728btu:TradingAndBrokerageCoalDeliveriesMember2020-01-012020-12-310001064728btu:TradingAndBrokerageCoalDeliveriesMember2019-01-012019-12-310001064728us-gaap:FairValueMeasurementsRecurringMemberus-gaap:FairValueInputsLevel1Memberus-gaap:ForeignExchangeContractMember2021-12-310001064728us-gaap:FairValueInputsLevel2Memberus-gaap:FairValueMeasurementsRecurringMemberus-gaap:ForeignExchangeContractMember2021-12-310001064728us-gaap:FairValueMeasurementsRecurringMemberus-gaap:FairValueInputsLevel3Memberus-gaap:ForeignExchangeContractMember2021-12-310001064728us-gaap:FairValueMeasurementsRecurringMemberus-gaap:ForeignExchangeContractMember2021-12-310001064728us-gaap:FairValueMeasurementsRecurringMemberbtu:PhysicalCommodityPurchaseSaleContractsMemberus-gaap:FairValueInputsLevel1Member2021-12-310001064728us-gaap:FairValueInputsLevel2Memberus-gaap:FairValueMeasurementsRecurringMemberbtu:PhysicalCommodityPurchaseSaleContractsMember2021-12-310001064728us-gaap:FairValueMeasurementsRecurringMemberbtu:PhysicalCommodityPurchaseSaleContractsMemberus-gaap:FairValueInputsLevel3Member2021-12-310001064728btu:PhysicalCommodityPurchaseSaleContractsMemberus-gaap:FairValueMeasurementsRecurringMember2021-12-310001064728us-gaap:FairValueMeasurementsRecurringMemberus-gaap:FairValueInputsLevel1Memberus-gaap:CoalContractMember2021-12-310001064728us-gaap:FairValueInputsLevel2Memberus-gaap:FairValueMeasurementsRecurringMemberus-gaap:CoalContractMember2021-12-310001064728us-gaap:FairValueMeasurementsRecurringMemberus-gaap:FairValueInputsLevel3Memberus-gaap:CoalContractMember2021-12-310001064728us-gaap:FairValueMeasurementsRecurringMemberus-gaap:CoalContractMember2021-12-310001064728us-gaap:FairValueMeasurementsRecurringMemberus-gaap:FairValueInputsLevel1Memberus-gaap:EquitySecuritiesMember2021-12-310001064728us-gaap:FairValueInputsLevel2Memberus-gaap:FairValueMeasurementsRecurringMemberus-gaap:EquitySecuritiesMember2021-12-310001064728us-gaap:FairValueMeasurementsRecurringMemberus-gaap:FairValueInputsLevel3Memberus-gaap:EquitySecuritiesMember2021-12-310001064728us-gaap:FairValueMeasurementsRecurringMemberus-gaap:EquitySecuritiesMember2021-12-310001064728us-gaap:FairValueMeasurementsRecurringMemberus-gaap:FairValueInputsLevel1Member2021-12-310001064728us-gaap:FairValueInputsLevel2Memberus-gaap:FairValueMeasurementsRecurringMember2021-12-310001064728us-gaap:FairValueMeasurementsRecurringMemberus-gaap:FairValueInputsLevel3Member2021-12-310001064728us-gaap:FairValueMeasurementsRecurringMember2021-12-310001064728us-gaap:FairValueMeasurementsRecurringMemberus-gaap:FairValueInputsLevel1Memberus-gaap:ForeignExchangeContractMember2020-12-310001064728us-gaap:FairValueInputsLevel2Memberus-gaap:FairValueMeasurementsRecurringMemberus-gaap:ForeignExchangeContractMember2020-12-310001064728us-gaap:FairValueMeasurementsRecurringMemberus-gaap:FairValueInputsLevel3Memberus-gaap:ForeignExchangeContractMember2020-12-310001064728us-gaap:FairValueMeasurementsRecurringMemberus-gaap:ForeignExchangeContractMember2020-12-310001064728us-gaap:FairValueMeasurementsRecurringMemberbtu:PhysicalCommodityPurchaseSaleContractsMemberus-gaap:FairValueInputsLevel1Member2020-12-310001064728us-gaap:FairValueInputsLevel2Memberus-gaap:FairValueMeasurementsRecurringMemberbtu:PhysicalCommodityPurchaseSaleContractsMember2020-12-310001064728us-gaap:FairValueMeasurementsRecurringMemberbtu:PhysicalCommodityPurchaseSaleContractsMemberus-gaap:FairValueInputsLevel3Member2020-12-310001064728btu:PhysicalCommodityPurchaseSaleContractsMemberus-gaap:FairValueMeasurementsRecurringMember2020-12-310001064728us-gaap:FairValueMeasurementsRecurringMemberus-gaap:FairValueInputsLevel1Memberus-gaap:CoalContractMember2020-12-310001064728us-gaap:FairValueInputsLevel2Memberus-gaap:FairValueMeasurementsRecurringMemberus-gaap:CoalContractMember2020-12-310001064728us-gaap:FairValueMeasurementsRecurringMemberus-gaap:FairValueInputsLevel3Memberus-gaap:CoalContractMember2020-12-310001064728us-gaap:FairValueMeasurementsRecurringMemberus-gaap:CoalContractMember2020-12-310001064728us-gaap:FairValueMeasurementsRecurringMemberus-gaap:FairValueInputsLevel1Memberus-gaap:EquitySecuritiesMember2020-12-310001064728us-gaap:FairValueInputsLevel2Memberus-gaap:FairValueMeasurementsRecurringMemberus-gaap:EquitySecuritiesMember2020-12-310001064728us-gaap:FairValueMeasurementsRecurringMemberus-gaap:FairValueInputsLevel3Memberus-gaap:EquitySecuritiesMember2020-12-310001064728us-gaap:FairValueMeasurementsRecurringMemberus-gaap:EquitySecuritiesMember2020-12-310001064728us-gaap:FairValueMeasurementsRecurringMemberus-gaap:FairValueInputsLevel1Member2020-12-310001064728us-gaap:FairValueInputsLevel2Memberus-gaap:FairValueMeasurementsRecurringMember2020-12-310001064728us-gaap:FairValueMeasurementsRecurringMemberus-gaap:FairValueInputsLevel3Member2020-12-310001064728us-gaap:FairValueMeasurementsRecurringMember2020-12-310001064728us-gaap:CarryingReportedAmountFairValueDisclosureMember2021-12-310001064728us-gaap:CarryingReportedAmountFairValueDisclosureMember2020-12-310001064728us-gaap:EstimateOfFairValueFairValueDisclosureMember2021-12-310001064728us-gaap:EstimateOfFairValueFairValueDisclosureMember2020-12-310001064728btu:CoalTradingMember2019-12-310001064728btu:CoalTradingMember2018-12-310001064728btu:CoalTradingMember2021-01-012021-12-310001064728btu:CoalTradingMember2020-01-012020-12-310001064728btu:CoalTradingMember2019-01-012019-12-310001064728us-gaap:ProductiveLandMember2021-12-310001064728us-gaap:ProductiveLandMember2020-12-310001064728us-gaap:BuildingAndBuildingImprovementsMember2021-12-310001064728us-gaap:BuildingAndBuildingImprovementsMember2020-12-310001064728us-gaap:MachineryAndEquipmentMember2021-12-310001064728us-gaap:MachineryAndEquipmentMember2020-12-310001064728btu:MiscellaneousReceivablesMember2021-12-310001064728btu:MiscellaneousReceivablesMember2020-12-310001064728btu:CoalReservesHeldByFeeOwnershipMember2021-12-310001064728btu:CoalReservesHeldByFeeOwnershipMember2020-12-310001064728us-gaap:DomesticCountryMember2021-12-310001064728us-gaap:ForeignCountryMember2021-12-310001064728us-gaap:DomesticCountryMember2021-01-012021-12-310001064728us-gaap:DomesticCountryMember2020-01-012020-12-310001064728us-gaap:DomesticCountryMember2019-01-012019-12-310001064728us-gaap:StateAndLocalJurisdictionMember2021-01-012021-12-310001064728us-gaap:StateAndLocalJurisdictionMember2020-01-012020-12-310001064728us-gaap:StateAndLocalJurisdictionMember2019-01-012019-12-310001064728us-gaap:ForeignCountryMember2021-01-012021-12-310001064728us-gaap:ForeignCountryMember2020-01-012020-12-310001064728us-gaap:ForeignCountryMember2019-01-012019-12-310001064728btu:A6.000SeniorSecuredNotesDue2022Memberus-gaap:SeniorNotesMember2021-12-310001064728btu:A6.000SeniorSecuredNotesDue2022Memberus-gaap:SeniorNotesMember2020-12-310001064728us-gaap:SeniorNotesMemberbtu:A8500SeniorSecuredNotesDue2024Member2021-12-310001064728us-gaap:SeniorNotesMemberbtu:A8500SeniorSecuredNotesDue2024Member2020-12-310001064728us-gaap:SeniorNotesMemberbtu:A1000SeniorSecuredNotesDue2024Member2021-12-310001064728us-gaap:SeniorNotesMemberbtu:A1000SeniorSecuredNotesDue2024Member2020-12-310001064728btu:TermLoanMemberbtu:SeniorSecuredTermLoanDue2024Member2021-12-310001064728btu:TermLoanMemberbtu:SeniorSecuredTermLoanDue2024Member2020-12-310001064728us-gaap:SeniorNotesMemberbtu:A6.375SeniorSecuredNotesDue2025Member2021-12-310001064728us-gaap:SeniorNotesMemberbtu:A6.375SeniorSecuredNotesDue2025Member2020-12-310001064728btu:SeniorSecuredTermLoanDue2022Memberbtu:TermLoanMember2021-12-310001064728btu:SeniorSecuredTermLoanDue2022Memberbtu:TermLoanMember2020-12-310001064728us-gaap:RevolvingCreditFacilityMember2021-12-310001064728us-gaap:RevolvingCreditFacilityMember2020-12-310001064728btu:A6.000SeniorSecuredNotesDue2022Memberus-gaap:SeniorNotesMember2021-01-290001064728us-gaap:SeniorNotesMemberbtu:A1000SeniorSecuredNotesDue2024Member2021-01-290001064728us-gaap:SeniorNotesMemberbtu:A8500SeniorSecuredNotesDue2024Member2021-01-2900010647282021-01-292021-01-290001064728btu:A6.000SeniorSecuredNotesDue2022Member2021-01-012021-12-310001064728us-gaap:RevolvingCreditFacilityMemberus-gaap:LineOfCreditMember2021-01-292021-01-290001064728btu:TermLoanMemberbtu:SeniorSecuredTermLoanDue2024Member2021-01-292021-01-290001064728us-gaap:SeniorNotesMemberbtu:A1000SeniorSecuredNotesDue2024Member2021-01-012021-12-310001064728btu:TermLoanMemberbtu:SeniorSecuredTermLoanDue2024Member2021-01-290001064728btu:TermLoanMemberbtu:SeniorSecuredTermLoanDue2024Member2021-01-012021-12-310001064728us-gaap:SeniorNotesMemberbtu:A8500SeniorSecuredNotesDue2024Member2021-01-012021-12-310001064728us-gaap:LetterOfCreditMemberus-gaap:LineOfCreditMember2021-01-292021-01-290001064728us-gaap:LetterOfCreditMemberus-gaap:LineOfCreditMember2021-01-290001064728us-gaap:LetterOfCreditMemberus-gaap:LineOfCreditMember2021-01-012021-12-310001064728btu:A2017RevolverMemberus-gaap:RevolvingCreditFacilityMember2021-01-290001064728btu:EffectofReorganizationPlanMemberus-gaap:SeniorNotesMemberbtu:A6.375SeniorSecuredNotesDue2025Member2017-02-150001064728us-gaap:SeniorNotesMemberbtu:A6.375SeniorSecuredNotesDue2025Member2017-02-150001064728us-gaap:SeniorNotesMemberbtu:A6.375SeniorSecuredNotesDue2025Member2021-01-012021-12-310001064728us-gaap:SeniorNotesMemberbtu:A6.375SeniorSecuredNotesDue2025Member2020-01-012020-12-310001064728us-gaap:SeniorNotesMemberbtu:A6.375SeniorSecuredNotesDue2025Member2019-01-012019-12-310001064728us-gaap:GeographicDistributionDomesticMemberus-gaap:SeniorNotesMemberbtu:A6.375SeniorSecuredNotesDue2025Member2021-12-310001064728us-gaap:SeniorNotesMemberbtu:A6.375SeniorSecuredNotesDue2025Memberus-gaap:GeographicDistributionForeignMember2021-12-310001064728btu:TermLoanMemberbtu:EffectofReorganizationPlanMemberbtu:SuccessorCreditAgreementMember2017-04-030001064728btu:TermLoanMemberbtu:SuccessorCreditAgreementMember2017-04-030001064728btu:TermLoanMemberbtu:SuccessorCreditAgreementMember2018-04-012018-04-300001064728btu:TermLoanMemberbtu:SuccessorCreditAgreementMember2020-12-310001064728btu:TermLoanMemberbtu:SuccessorCreditAgreementMember2017-04-022021-09-300001064728btu:TermLoanMemberbtu:SeniorSecuredTermLoanDue2025Member2021-12-310001064728btu:TermLoanMemberbtu:SuccessorCreditAgreementMember2021-01-012021-12-310001064728btu:TermLoanMemberbtu:SuccessorCreditAgreementMember2020-01-012020-12-310001064728btu:TermLoanMemberbtu:SuccessorCreditAgreementMember2019-01-012019-12-310001064728us-gaap:LondonInterbankOfferedRateLIBORMemberbtu:TermLoanMemberbtu:SuccessorCreditAgreementMember2021-01-012021-12-310001064728btu:A2017RevolverMemberus-gaap:RevolvingCreditFacilityMember2021-01-012021-12-310001064728btu:A2017RevolverMemberus-gaap:RevolvingCreditFacilityMember2020-01-012020-12-310001064728btu:A2017RevolverMemberus-gaap:RevolvingCreditFacilityMember2019-01-012019-12-310001064728btu:AtMarketIssuanceMember2021-06-040001064728btu:AtMarketIssuanceMember2021-12-310001064728btu:OpenMarketPurchaseMemberus-gaap:SeniorNotesMemberbtu:A8500SeniorSecuredNotesDue2024Member2021-01-012021-12-310001064728btu:OpenMarketPurchaseMemberus-gaap:SeniorNotesMemberbtu:A6.375SeniorSecuredNotesDue2025Member2021-01-012021-12-310001064728btu:OpenMarketPurchaseMemberbtu:TermLoanMemberbtu:SeniorSecuredTermLoanDue2025Member2021-01-012021-12-310001064728btu:OpenMarketPurchaseMember2021-01-012021-12-310001064728btu:DebtForEquityExchangeMember2021-01-012021-12-310001064728us-gaap:SubsequentEventMemberus-gaap:SeniorNotesMemberbtu:A8500SeniorSecuredNotesDue2024Member2022-01-140001064728us-gaap:LongTermDebtMember2021-12-310001064728us-gaap:LongTermDebtMember2020-12-310001064728srt:MinimumMember2021-01-012021-12-310001064728srt:MaximumMember2021-01-012021-12-310001064728btu:LOM3YearsorLessMember2021-12-310001064728btu:LOMGreaterthan20YearsMember2021-12-310001064728btu:LOM3YearsorLessMember2020-12-310001064728btu:LOMGreaterthan20YearsMember2020-12-310001064728us-gaap:OtherPostretirementBenefitPlansDefinedBenefitMember2021-01-012021-12-310001064728us-gaap:OtherPostretirementBenefitPlansDefinedBenefitMember2020-01-012020-12-310001064728us-gaap:OtherPostretirementBenefitPlansDefinedBenefitMember2019-01-012019-12-310001064728us-gaap:OtherPostretirementBenefitPlansDefinedBenefitMember2021-12-310001064728us-gaap:OtherPostretirementBenefitPlansDefinedBenefitMember2020-12-310001064728us-gaap:OtherPostretirementBenefitPlansDefinedBenefitMember2019-12-310001064728us-gaap:OtherPostretirementBenefitPlansDefinedBenefitMemberbtu:RetirementPlanAmendmentOneMember2020-01-012020-12-310001064728us-gaap:OtherPostretirementBenefitPlansDefinedBenefitMemberbtu:RetirementPlanAmendmentOneMember2021-01-012021-12-310001064728btu:RetirementPlanAmendmentTwoMemberus-gaap:OtherPostretirementBenefitPlansDefinedBenefitMember2020-01-012020-12-310001064728btu:RetirementPlanAmendmentTwoMemberus-gaap:OtherPostretirementBenefitPlansDefinedBenefitMember2021-01-012021-12-310001064728srt:MaximumMemberus-gaap:OtherPostretirementBenefitPlansDefinedBenefitMember2021-01-012021-12-310001064728btu:PreMedicareMember2021-12-310001064728btu:PreMedicareMember2020-12-310001064728btu:PostMedicareMember2021-12-310001064728btu:PostMedicareMember2020-12-31btu:numberOfTrust0001064728us-gaap:DefinedBenefitPlanEquitySecuritiesMember2021-12-310001064728us-gaap:FixedIncomeSecuritiesMember2021-12-310001064728us-gaap:OtherPostretirementBenefitPlansDefinedBenefitMemberus-gaap:FairValueInputsLevel1Memberus-gaap:EquitySecuritiesMember2021-12-310001064728us-gaap:FairValueInputsLevel2Memberus-gaap:OtherPostretirementBenefitPlansDefinedBenefitMemberus-gaap:EquitySecuritiesMember2021-12-310001064728us-gaap:OtherPostretirementBenefitPlansDefinedBenefitMemberus-gaap:FairValueInputsLevel3Memberus-gaap:EquitySecuritiesMember2021-12-310001064728us-gaap:OtherPostretirementBenefitPlansDefinedBenefitMemberus-gaap:EquitySecuritiesMember2021-12-310001064728btu:InternationalEquitySecuritiesMemberus-gaap:OtherPostretirementBenefitPlansDefinedBenefitMemberus-gaap:FairValueInputsLevel1Member2021-12-310001064728us-gaap:FairValueInputsLevel2Memberbtu:InternationalEquitySecuritiesMemberus-gaap:OtherPostretirementBenefitPlansDefinedBenefitMember2021-12-310001064728btu:InternationalEquitySecuritiesMemberus-gaap:OtherPostretirementBenefitPlansDefinedBenefitMemberus-gaap:FairValueInputsLevel3Member2021-12-310001064728btu:InternationalEquitySecuritiesMemberus-gaap:OtherPostretirementBenefitPlansDefinedBenefitMember2021-12-310001064728us-gaap:OtherPostretirementBenefitPlansDefinedBenefitMemberus-gaap:FairValueInputsLevel1Memberus-gaap:CorporateDebtSecuritiesMember2021-12-310001064728us-gaap:FairValueInputsLevel2Memberus-gaap:OtherPostretirementBenefitPlansDefinedBenefitMemberus-gaap:CorporateDebtSecuritiesMember2021-12-310001064728us-gaap:OtherPostretirementBenefitPlansDefinedBenefitMemberus-gaap:CorporateDebtSecuritiesMemberus-gaap:FairValueInputsLevel3Member2021-12-310001064728us-gaap:OtherPostretirementBenefitPlansDefinedBenefitMemberus-gaap:CorporateDebtSecuritiesMember2021-12-310001064728us-gaap:OtherPostretirementBenefitPlansDefinedBenefitMemberus-gaap:USTreasuryAndGovernmentMemberus-gaap:FairValueInputsLevel1Member2021-12-310001064728us-gaap:FairValueInputsLevel2Memberus-gaap:OtherPostretirementBenefitPlansDefinedBenefitMemberus-gaap:USTreasuryAndGovernmentMember2021-12-310001064728us-gaap:OtherPostretirementBenefitPlansDefinedBenefitMemberus-gaap:USTreasuryAndGovernmentMemberus-gaap:FairValueInputsLevel3Member2021-12-310001064728us-gaap:OtherPostretirementBenefitPlansDefinedBenefitMemberus-gaap:USTreasuryAndGovernmentMember2021-12-310001064728us-gaap:OtherPostretirementBenefitPlansDefinedBenefitMemberus-gaap:FairValueInputsLevel1Memberus-gaap:MoneyMarketFundsMember2021-12-310001064728us-gaap:FairValueInputsLevel2Memberus-gaap:OtherPostretirementBenefitPlansDefinedBenefitMemberus-gaap:MoneyMarketFundsMember2021-12-310001064728us-gaap:OtherPostretirementBenefitPlansDefinedBenefitMemberus-gaap:FairValueInputsLevel3Memberus-gaap:MoneyMarketFundsMember2021-12-310001064728us-gaap:OtherPostretirementBenefitPlansDefinedBenefitMemberus-gaap:MoneyMarketFundsMember2021-12-310001064728us-gaap:OtherPostretirementBenefitPlansDefinedBenefitMemberus-gaap:FairValueInputsLevel1Member2021-12-310001064728us-gaap:FairValueInputsLevel2Memberus-gaap:OtherPostretirementBenefitPlansDefinedBenefitMember2021-12-310001064728us-gaap:OtherPostretirementBenefitPlansDefinedBenefitMemberus-gaap:FairValueInputsLevel3Member2021-12-310001064728us-gaap:OtherPostretirementBenefitPlansDefinedBenefitMemberus-gaap:FairValueInputsLevel1Memberus-gaap:EquitySecuritiesMember2020-12-310001064728us-gaap:FairValueInputsLevel2Memberus-gaap:OtherPostretirementBenefitPlansDefinedBenefitMemberus-gaap:EquitySecuritiesMember2020-12-310001064728us-gaap:OtherPostretirementBenefitPlansDefinedBenefitMemberus-gaap:FairValueInputsLevel3Memberus-gaap:EquitySecuritiesMember2020-12-310001064728us-gaap:OtherPostretirementBenefitPlansDefinedBenefitMemberus-gaap:EquitySecuritiesMember2020-12-310001064728btu:InternationalEquitySecuritiesMemberus-gaap:OtherPostretirementBenefitPlansDefinedBenefitMemberus-gaap:FairValueInputsLevel1Member2020-12-310001064728us-gaap:FairValueInputsLevel2Memberbtu:InternationalEquitySecuritiesMemberus-gaap:OtherPostretirementBenefitPlansDefinedBenefitMember2020-12-310001064728btu:InternationalEquitySecuritiesMemberus-gaap:OtherPostretirementBenefitPlansDefinedBenefitMemberus-gaap:FairValueInputsLevel3Member2020-12-310001064728btu:InternationalEquitySecuritiesMemberus-gaap:OtherPostretirementBenefitPlansDefinedBenefitMember2020-12-310001064728us-gaap:OtherPostretirementBenefitPlansDefinedBenefitMemberus-gaap:FairValueInputsLevel1Memberus-gaap:CorporateDebtSecuritiesMember2020-12-310001064728us-gaap:FairValueInputsLevel2Memberus-gaap:OtherPostretirementBenefitPlansDefinedBenefitMemberus-gaap:CorporateDebtSecuritiesMember2020-12-310001064728us-gaap:OtherPostretirementBenefitPlansDefinedBenefitMemberus-gaap:CorporateDebtSecuritiesMemberus-gaap:FairValueInputsLevel3Member2020-12-310001064728us-gaap:OtherPostretirementBenefitPlansDefinedBenefitMemberus-gaap:CorporateDebtSecuritiesMember2020-12-310001064728us-gaap:OtherPostretirementBenefitPlansDefinedBenefitMemberus-gaap:USTreasuryAndGovernmentMemberus-gaap:FairValueInputsLevel1Member2020-12-310001064728us-gaap:FairValueInputsLevel2Memberus-gaap:OtherPostretirementBenefitPlansDefinedBenefitMemberus-gaap:USTreasuryAndGovernmentMember2020-12-310001064728us-gaap:OtherPostretirementBenefitPlansDefinedBenefitMemberus-gaap:USTreasuryAndGovernmentMemberus-gaap:FairValueInputsLevel3Member2020-12-310001064728us-gaap:OtherPostretirementBenefitPlansDefinedBenefitMemberus-gaap:USTreasuryAndGovernmentMember2020-12-310001064728us-gaap:OtherPostretirementBenefitPlansDefinedBenefitMemberus-gaap:FairValueInputsLevel1Memberus-gaap:MoneyMarketFundsMember2020-12-310001064728us-gaap:FairValueInputsLevel2Memberus-gaap:OtherPostretirementBenefitPlansDefinedBenefitMemberus-gaap:MoneyMarketFundsMember2020-12-310001064728us-gaap:OtherPostretirementBenefitPlansDefinedBenefitMemberus-gaap:FairValueInputsLevel3Memberus-gaap:MoneyMarketFundsMember2020-12-310001064728us-gaap:OtherPostretirementBenefitPlansDefinedBenefitMemberus-gaap:MoneyMarketFundsMember2020-12-310001064728us-gaap:OtherPostretirementBenefitPlansDefinedBenefitMemberus-gaap:FairValueInputsLevel1Member2020-12-310001064728us-gaap:FairValueInputsLevel2Memberus-gaap:OtherPostretirementBenefitPlansDefinedBenefitMember2020-12-310001064728us-gaap:OtherPostretirementBenefitPlansDefinedBenefitMemberus-gaap:FairValueInputsLevel3Member2020-12-310001064728us-gaap:PensionPlansDefinedBenefitMember2020-01-012020-12-310001064728us-gaap:PensionPlansDefinedBenefitMember2021-01-012021-12-310001064728us-gaap:PensionPlansDefinedBenefitMember2019-01-012019-12-310001064728us-gaap:PensionPlansDefinedBenefitMember2020-12-310001064728us-gaap:PensionPlansDefinedBenefitMember2019-12-310001064728us-gaap:PensionPlansDefinedBenefitMember2021-12-310001064728srt:ScenarioForecastMemberus-gaap:PensionPlansDefinedBenefitMember2022-01-012022-12-310001064728btu:PeabodyPlanMember2021-12-310001064728btu:PeabodyPlanMember2020-12-310001064728btu:WesternPlanMember2021-12-310001064728btu:WesternPlanMember2020-12-310001064728us-gaap:FixedIncomeInvestmentsMember2021-12-310001064728us-gaap:FixedIncomeInvestmentsMember2020-12-310001064728us-gaap:RealEstateMember2021-12-310001064728us-gaap:RealEstateMember2020-12-310001064728us-gaap:FairValueInputsLevel1Memberus-gaap:CorporateDebtSecuritiesMemberus-gaap:PensionPlansDefinedBenefitMember2021-12-310001064728us-gaap:FairValueInputsLevel2Memberus-gaap:CorporateDebtSecuritiesMemberus-gaap:PensionPlansDefinedBenefitMember2021-12-310001064728us-gaap:CorporateDebtSecuritiesMemberus-gaap:FairValueInputsLevel3Memberus-gaap:PensionPlansDefinedBenefitMember2021-12-310001064728us-gaap:CorporateDebtSecuritiesMemberus-gaap:FairValueInputsLevel12And3Memberus-gaap:PensionPlansDefinedBenefitMember2021-12-310001064728us-gaap:USTreasuryAndGovernmentMemberus-gaap:FairValueInputsLevel1Memberus-gaap:PensionPlansDefinedBenefitMember2021-12-310001064728us-gaap:FairValueInputsLevel2Memberus-gaap:USTreasuryAndGovernmentMemberus-gaap:PensionPlansDefinedBenefitMember2021-12-310001064728us-gaap:USTreasuryAndGovernmentMemberus-gaap:FairValueInputsLevel3Memberus-gaap:PensionPlansDefinedBenefitMember2021-12-310001064728us-gaap:USTreasuryAndGovernmentMemberus-gaap:FairValueInputsLevel12And3Memberus-gaap:PensionPlansDefinedBenefitMember2021-12-310001064728us-gaap:FairValueInputsLevel1Memberus-gaap:PensionPlansDefinedBenefitMemberus-gaap:ForeignGovernmentDebtSecuritiesMember2021-12-310001064728us-gaap:FairValueInputsLevel2Memberus-gaap:PensionPlansDefinedBenefitMemberus-gaap:ForeignGovernmentDebtSecuritiesMember2021-12-310001064728us-gaap:FairValueInputsLevel3Memberus-gaap:PensionPlansDefinedBenefitMemberus-gaap:ForeignGovernmentDebtSecuritiesMember2021-12-310001064728us-gaap:FairValueInputsLevel12And3Memberus-gaap:PensionPlansDefinedBenefitMemberus-gaap:ForeignGovernmentDebtSecuritiesMember2021-12-310001064728us-gaap:FairValueInputsLevel1Memberus-gaap:AssetBackedSecuritiesMemberus-gaap:PensionPlansDefinedBenefitMember2021-12-310001064728us-gaap:FairValueInputsLevel2Memberus-gaap:AssetBackedSecuritiesMemberus-gaap:PensionPlansDefinedBenefitMember2021-12-310001064728us-gaap:FairValueInputsLevel3Memberus-gaap:AssetBackedSecuritiesMemberus-gaap:PensionPlansDefinedBenefitMember2021-12-310001064728us-gaap:FairValueInputsLevel12And3Memberus-gaap:AssetBackedSecuritiesMemberus-gaap:PensionPlansDefinedBenefitMember2021-12-310001064728us-gaap:FairValueInputsLevel1Memberus-gaap:ShortTermInvestmentsMemberus-gaap:PensionPlansDefinedBenefitMember2021-12-310001064728us-gaap:FairValueInputsLevel2Memberus-gaap:ShortTermInvestmentsMemberus-gaap:PensionPlansDefinedBenefitMember2021-12-310001064728us-gaap:ShortTermInvestmentsMemberus-gaap:FairValueInputsLevel3Memberus-gaap:PensionPlansDefinedBenefitMember2021-12-310001064728us-gaap:ShortTermInvestmentsMemberus-gaap:FairValueInputsLevel12And3Memberus-gaap:PensionPlansDefinedBenefitMember2021-12-310001064728us-gaap:FairValueInputsLevel1Memberus-gaap:RealEstateInvestmentMemberus-gaap:PensionPlansDefinedBenefitMember2021-12-310001064728us-gaap:FairValueInputsLevel2Memberus-gaap:RealEstateInvestmentMemberus-gaap:PensionPlansDefinedBenefitMember2021-12-310001064728us-gaap:FairValueInputsLevel3Memberus-gaap:RealEstateInvestmentMemberus-gaap:PensionPlansDefinedBenefitMember2021-12-310001064728us-gaap:FairValueInputsLevel12And3Memberus-gaap:RealEstateInvestmentMemberus-gaap:PensionPlansDefinedBenefitMember2021-12-310001064728us-gaap:FairValueInputsLevel1Memberus-gaap:PensionPlansDefinedBenefitMember2021-12-310001064728us-gaap:FairValueInputsLevel2Memberus-gaap:PensionPlansDefinedBenefitMember2021-12-310001064728us-gaap:FairValueInputsLevel3Memberus-gaap:PensionPlansDefinedBenefitMember2021-12-310001064728us-gaap:FairValueInputsLevel12And3Memberus-gaap:PensionPlansDefinedBenefitMember2021-12-310001064728us-gaap:PrivateEquityFundsMemberus-gaap:FairValueMeasuredAtNetAssetValuePerShareMemberus-gaap:PensionPlansDefinedBenefitMember2021-12-310001064728us-gaap:FairValueInputsLevel1Memberus-gaap:CorporateDebtSecuritiesMemberus-gaap:PensionPlansDefinedBenefitMember2020-12-310001064728us-gaap:FairValueInputsLevel2Memberus-gaap:CorporateDebtSecuritiesMemberus-gaap:PensionPlansDefinedBenefitMember2020-12-310001064728us-gaap:CorporateDebtSecuritiesMemberus-gaap:FairValueInputsLevel3Memberus-gaap:PensionPlansDefinedBenefitMember2020-12-310001064728us-gaap:CorporateDebtSecuritiesMemberus-gaap:FairValueInputsLevel12And3Memberus-gaap:PensionPlansDefinedBenefitMember2020-12-310001064728us-gaap:USTreasuryAndGovernmentMemberus-gaap:FairValueInputsLevel1Memberus-gaap:PensionPlansDefinedBenefitMember2020-12-310001064728us-gaap:FairValueInputsLevel2Memberus-gaap:USTreasuryAndGovernmentMemberus-gaap:PensionPlansDefinedBenefitMember2020-12-310001064728us-gaap:USTreasuryAndGovernmentMemberus-gaap:FairValueInputsLevel3Memberus-gaap:PensionPlansDefinedBenefitMember2020-12-310001064728us-gaap:USTreasuryAndGovernmentMemberus-gaap:FairValueInputsLevel12And3Memberus-gaap:PensionPlansDefinedBenefitMember2020-12-310001064728us-gaap:FairValueInputsLevel1Memberus-gaap:PensionPlansDefinedBenefitMemberus-gaap:ForeignGovernmentDebtSecuritiesMember2020-12-310001064728us-gaap:FairValueInputsLevel2Memberus-gaap:PensionPlansDefinedBenefitMemberus-gaap:ForeignGovernmentDebtSecuritiesMember2020-12-310001064728us-gaap:FairValueInputsLevel3Memberus-gaap:PensionPlansDefinedBenefitMemberus-gaap:ForeignGovernmentDebtSecuritiesMember2020-12-310001064728us-gaap:FairValueInputsLevel12And3Memberus-gaap:PensionPlansDefinedBenefitMemberus-gaap:ForeignGovernmentDebtSecuritiesMember2020-12-310001064728us-gaap:FairValueInputsLevel1Memberus-gaap:AssetBackedSecuritiesMemberus-gaap:PensionPlansDefinedBenefitMember2020-12-310001064728us-gaap:FairValueInputsLevel2Memberus-gaap:AssetBackedSecuritiesMemberus-gaap:PensionPlansDefinedBenefitMember2020-12-310001064728us-gaap:FairValueInputsLevel3Memberus-gaap:AssetBackedSecuritiesMemberus-gaap:PensionPlansDefinedBenefitMember2020-12-310001064728us-gaap:FairValueInputsLevel12And3Memberus-gaap:AssetBackedSecuritiesMemberus-gaap:PensionPlansDefinedBenefitMember2020-12-310001064728us-gaap:FairValueInputsLevel1Memberus-gaap:ShortTermInvestmentsMemberus-gaap:PensionPlansDefinedBenefitMember2020-12-310001064728us-gaap:FairValueInputsLevel2Memberus-gaap:ShortTermInvestmentsMemberus-gaap:PensionPlansDefinedBenefitMember2020-12-310001064728us-gaap:ShortTermInvestmentsMemberus-gaap:FairValueInputsLevel3Memberus-gaap:PensionPlansDefinedBenefitMember2020-12-310001064728us-gaap:ShortTermInvestmentsMemberus-gaap:FairValueInputsLevel12And3Memberus-gaap:PensionPlansDefinedBenefitMember2020-12-310001064728us-gaap:FairValueInputsLevel1Memberus-gaap:RealEstateInvestmentMemberus-gaap:PensionPlansDefinedBenefitMember2020-12-310001064728us-gaap:FairValueInputsLevel2Memberus-gaap:RealEstateInvestmentMemberus-gaap:PensionPlansDefinedBenefitMember2020-12-310001064728us-gaap:FairValueInputsLevel3Memberus-gaap:RealEstateInvestmentMemberus-gaap:PensionPlansDefinedBenefitMember2020-12-310001064728us-gaap:FairValueInputsLevel12And3Memberus-gaap:RealEstateInvestmentMemberus-gaap:PensionPlansDefinedBenefitMember2020-12-310001064728us-gaap:FairValueInputsLevel1Memberus-gaap:PensionPlansDefinedBenefitMember2020-12-310001064728us-gaap:FairValueInputsLevel2Memberus-gaap:PensionPlansDefinedBenefitMember2020-12-310001064728us-gaap:FairValueInputsLevel3Memberus-gaap:PensionPlansDefinedBenefitMember2020-12-310001064728us-gaap:FairValueInputsLevel12And3Memberus-gaap:PensionPlansDefinedBenefitMember2020-12-310001064728us-gaap:PrivateEquityFundsMemberus-gaap:FairValueMeasuredAtNetAssetValuePerShareMemberus-gaap:PensionPlansDefinedBenefitMember2020-12-310001064728us-gaap:FairValueInputsLevel3Member2020-12-310001064728us-gaap:FairValueInputsLevel3Member2019-12-310001064728us-gaap:FairValueInputsLevel3Member2018-12-310001064728us-gaap:FairValueInputsLevel3Member2021-01-012021-12-310001064728us-gaap:FairValueInputsLevel3Member2020-01-012020-12-310001064728us-gaap:FairValueInputsLevel3Member2019-01-012019-12-310001064728us-gaap:FairValueInputsLevel3Member2021-12-3100010647282017-01-012017-04-01btu:numberOfPlan0001064728us-gaap:ForeignPlanMember2021-01-012021-12-310001064728us-gaap:ForeignPlanMember2020-01-012020-12-310001064728us-gaap:ForeignPlanMember2019-01-012019-12-31btu:numberOfVote0001064728btu:DebtForEquityExchangeMember2020-12-310001064728btu:DebtForEquityExchangeMember2019-12-310001064728btu:AtMarketIssuanceMember2020-12-310001064728btu:AtMarketIssuanceMember2019-12-3100010647282017-08-0100010647282018-10-3000010647282017-04-022020-12-3100010647282018-01-012018-12-3100010647282017-04-022017-12-310001064728us-gaap:TreasuryStockMember2021-01-012021-12-310001064728us-gaap:TreasuryStockMember2019-01-012019-12-310001064728us-gaap:TreasuryStockMember2020-01-012020-12-310001064728btu:A2017IncentivePlanMember2018-12-310001064728btu:DeferredStockUnitsMember2020-01-012020-12-310001064728us-gaap:RestrictedStockUnitsRSUMember2021-01-012021-12-310001064728us-gaap:RestrictedStockUnitsRSUMember2020-12-310001064728us-gaap:RestrictedStockUnitsRSUMember2021-12-310001064728us-gaap:RestrictedStockUnitsRSUMember2020-01-012020-12-310001064728us-gaap:RestrictedStockUnitsRSUMember2019-01-012019-12-310001064728btu:DividendEquivalentUnitsMember2021-12-310001064728us-gaap:PerformanceSharesMember2021-01-012021-12-310001064728us-gaap:PerformanceSharesMember2020-12-310001064728us-gaap:PerformanceSharesMember2021-12-310001064728btu:DividendEquivalentUnitsPerformanceSharesMember2021-12-310001064728btu:TransitionAgreementMember2021-01-012021-12-310001064728us-gaap:PerformanceSharesMember2020-01-012020-12-310001064728us-gaap:AccumulatedTranslationAdjustmentMember2018-12-310001064728us-gaap:AccumulatedDefinedBenefitPlansAdjustmentNetPriorServiceCostCreditMember2018-12-310001064728us-gaap:AccumulatedTranslationAdjustmentMember2019-01-012019-12-310001064728us-gaap:AccumulatedDefinedBenefitPlansAdjustmentNetPriorServiceCostCreditMember2019-01-012019-12-310001064728us-gaap:AccumulatedTranslationAdjustmentMember2019-12-310001064728us-gaap:AccumulatedDefinedBenefitPlansAdjustmentNetPriorServiceCostCreditMember2019-12-310001064728us-gaap:AccumulatedTranslationAdjustmentMember2020-01-012020-12-310001064728us-gaap:AccumulatedDefinedBenefitPlansAdjustmentNetPriorServiceCostCreditMember2020-01-012020-12-310001064728us-gaap:AccumulatedTranslationAdjustmentMember2020-12-310001064728us-gaap:AccumulatedDefinedBenefitPlansAdjustmentNetPriorServiceCostCreditMember2020-12-310001064728us-gaap:AccumulatedTranslationAdjustmentMember2021-01-012021-12-310001064728us-gaap:AccumulatedDefinedBenefitPlansAdjustmentNetPriorServiceCostCreditMember2021-01-012021-12-310001064728us-gaap:AccumulatedTranslationAdjustmentMember2021-12-310001064728us-gaap:AccumulatedDefinedBenefitPlansAdjustmentNetPriorServiceCostCreditMember2021-12-310001064728us-gaap:AccumulatedDefinedBenefitPlansAdjustmentNetPriorServiceCostCreditMemberus-gaap:ReclassificationOutOfAccumulatedOtherComprehensiveIncomeMemberus-gaap:DefinedBenefitPostretirementHealthCoverageMember2021-01-012021-12-310001064728us-gaap:AccumulatedDefinedBenefitPlansAdjustmentNetPriorServiceCostCreditMemberus-gaap:ReclassificationOutOfAccumulatedOtherComprehensiveIncomeMemberus-gaap:DefinedBenefitPostretirementHealthCoverageMember2020-01-012020-12-310001064728us-gaap:AccumulatedDefinedBenefitPlansAdjustmentNetPriorServiceCostCreditMemberus-gaap:ReclassificationOutOfAccumulatedOtherComprehensiveIncomeMemberus-gaap:DefinedBenefitPostretirementHealthCoverageMember2019-01-012019-12-310001064728btu:MillenniumMineMember2021-01-012021-12-310001064728btu:WilkieCreekMineMember2021-01-012021-12-310001064728btu:NorthGoonyellaMineMember2019-03-012019-03-310001064728btu:NorthGoonyellaMineMember2021-01-012021-12-310001064728btu:NorthGoonyellaMineMember2020-01-012020-12-310001064728btu:NorthGoonyellaMineMember2019-01-012019-12-310001064728btu:MineCarryingValueMemberbtu:NorthGoonyellaMineMember2019-01-012019-12-31btu:numberOfEmployeebtu:numberOfMine0001064728btu:RepresentedByOrganizedLaborUnionMemberbtu:KayentaMineMember2021-12-310001064728btu:RepresentedByOrganizedLaborUnionMemberbtu:ShoalCreekMember2021-12-310001064728btu:RepresentedByOrganizedLaborUnionMemberbtu:WilpinjongMineMember2021-12-310001064728btu:RepresentedByOrganizedLaborUnionMemberbtu:CoppabellaMineMember2021-12-310001064728btu:RepresentedByOrganizedLaborUnionMemberbtu:MoorvaleMineMember2021-12-310001064728btu:RepresentedByOrganizedLaborUnionMemberbtu:MetropolitanUndergroundMineMember2021-12-310001064728btu:RepresentedByOrganizedLaborUnionMemberbtu:MetropolitanPrepPlantMember2021-12-310001064728btu:WamboUndergroundMineMemberbtu:RepresentedByOrganizedLaborUnionMember2021-12-310001064728btu:RepresentedByOrganizedLaborUnionMemberbtu:WamboPrepPlantMember2021-12-310001064728us-gaap:SuretyBondMember2020-11-060001064728btu:AccountsReceivableSecuritizationProgramApril32020Member2017-04-030001064728srt:ScenarioForecastMemberbtu:AccountsReceivableSecuritizationProgramApril32020Member2022-01-310001064728btu:AccountsReceivableSecuritizationProgramApril32020Memberus-gaap:LondonInterbankOfferedRateLiborSwapRateMemberus-gaap:SecuredDebtMember2021-01-012021-12-310001064728btu:AccountsReceivableSecuritizationProgramApril32020Memberus-gaap:SecuredDebtMember2021-12-310001064728btu:AccountsReceivableSecuritizationProgramApril32020Member2021-12-310001064728btu:AccountsReceivableSecuritizationProgramApril32020Memberus-gaap:SecuredDebtMember2021-01-012021-12-310001064728btu:AccountsReceivableSecuritizationProgramApril32020Memberus-gaap:SecuredDebtMember2020-01-012020-12-310001064728btu:AccountsReceivableSecuritizationProgramApril32020Memberus-gaap:SecuredDebtMember2019-01-012019-12-310001064728us-gaap:ObligationsMember2021-12-310001064728us-gaap:ObligationsMember2020-12-310001064728us-gaap:ObligationsMember2019-12-310001064728btu:AustralianMiningMember2019-01-012019-12-310001064728us-gaap:CapitalAdditionsMember2021-12-310001064728btu:SeaborneMiningMember2021-12-310001064728btu:U.SThermalMiningMember2021-12-310001064728us-gaap:CorporateAndOtherMember2021-12-310001064728btu:SeaborneMiningMember2020-12-310001064728btu:U.SThermalMiningMember2020-12-310001064728us-gaap:CorporateAndOtherMember2020-12-310001064728btu:SeaborneMiningMember2019-12-310001064728btu:U.SThermalMiningMember2019-12-310001064728us-gaap:CorporateAndOtherMember2019-12-310001064728country:US2021-01-012021-12-310001064728country:US2020-01-012020-12-310001064728country:US2019-01-012019-12-310001064728country:TW2021-01-012021-12-310001064728country:TW2020-01-012020-12-310001064728country:TW2019-01-012019-12-310001064728country:JP2021-01-012021-12-310001064728country:JP2020-01-012020-12-310001064728country:JP2019-01-012019-12-310001064728country:AU2021-01-012021-12-310001064728country:AU2020-01-012020-12-310001064728country:AU2019-01-012019-12-310001064728country:IN2021-01-012021-12-310001064728country:IN2020-01-012020-12-310001064728country:IN2019-01-012019-12-310001064728country:ID2021-01-012021-12-310001064728country:ID2020-01-012020-12-310001064728country:ID2019-01-012019-12-310001064728country:VN2021-01-012021-12-310001064728country:VN2020-01-012020-12-310001064728country:VN2019-01-012019-12-310001064728country:KP2021-01-012021-12-310001064728country:KP2020-01-012020-12-310001064728country:KP2019-01-012019-12-310001064728country:CN2021-01-012021-12-310001064728country:CN2020-01-012020-12-310001064728country:CN2019-01-012019-12-310001064728btu:OtherRegionsMember2021-01-012021-12-310001064728btu:OtherRegionsMember2020-01-012020-12-310001064728btu:OtherRegionsMember2019-01-012019-12-310001064728btu:AdvanceRoyaltyRecoupmentReserveMember2020-12-310001064728btu:AdvanceRoyaltyRecoupmentReserveMember2021-01-012021-12-310001064728btu:AdvanceRoyaltyRecoupmentReserveMember2021-12-310001064728btu:ReserveForMaterialsAndSuppliesMember2020-12-310001064728btu:ReserveForMaterialsAndSuppliesMember2021-01-012021-12-310001064728btu:ReserveForMaterialsAndSuppliesMember2021-12-310001064728us-gaap:ValuationAllowanceOfDeferredTaxAssetsMember2020-12-310001064728us-gaap:ValuationAllowanceOfDeferredTaxAssetsMember2021-01-012021-12-310001064728us-gaap:ValuationAllowanceOfDeferredTaxAssetsMember2021-12-310001064728btu:AdvanceRoyaltyRecoupmentReserveMember2019-12-310001064728btu:AdvanceRoyaltyRecoupmentReserveMember2020-01-012020-12-310001064728btu:ReserveForMaterialsAndSuppliesMember2019-12-310001064728btu:ReserveForMaterialsAndSuppliesMember2020-01-012020-12-310001064728us-gaap:ValuationAllowanceOfDeferredTaxAssetsMember2019-12-310001064728us-gaap:ValuationAllowanceOfDeferredTaxAssetsMember2020-01-012020-12-310001064728btu:AdvanceRoyaltyRecoupmentReserveMember2018-12-310001064728btu:AdvanceRoyaltyRecoupmentReserveMember2019-01-012019-12-310001064728btu:ReserveForMaterialsAndSuppliesMember2018-12-310001064728btu:ReserveForMaterialsAndSuppliesMember2019-01-012019-12-310001064728us-gaap:AllowanceForCreditLossMember2018-12-310001064728us-gaap:AllowanceForCreditLossMember2019-01-012019-12-310001064728us-gaap:AllowanceForCreditLossMember2019-12-310001064728us-gaap:ValuationAllowanceOfDeferredTaxAssetsMember2018-12-310001064728us-gaap:ValuationAllowanceOfDeferredTaxAssetsMember2019-01-012019-12-31

UNITED STATES

SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION

Washington, D.C. 20549

_____________________________________________

FORM 10-K

(Mark One)

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| ☑ | ANNUAL REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE

SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 | | |

| | For the Fiscal Year Ended | December 31, 2021 | | |

or

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| ☐ | TRANSITION REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE

SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 | | |

Commission File Number 1-16463

____________________________________________

PEABODY ENERGY CORPORATION

(Exact name of registrant as specified in its charter)

| | | | | | | | |

| Delaware | | 13-4004153 |

| (State or other jurisdiction of incorporation or organization) | | (I.R.S. Employer Identification No.) |

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| 701 Market Street, | St. Louis, | Missouri | | | 63101-1826 |

| (Address of principal executive offices) | | (Zip Code) |

(314) 342-3400

(Registrant’s telephone number, including area code)

Securities Registered Pursuant to Section 12(b) of the Act:

| | | | | | | | |

| Title of Each Class | Trading Symbol(s) | Name of Each Exchange on Which Registered |

| Common Stock, par value $0.01 per share | BTU | New York Stock Exchange |

Securities Registered Pursuant to Section 12(g) of the Act:

None

Indicate by check mark if the registrant is a well-known seasoned issuer, as defined in Rule 405 of the Securities Act. Yes ☐ No ☑

Indicate by check mark if the registrant is not required to file reports pursuant to Section 13 or Section 15(d) of the Act. Yes ☐ No ☑

Indicate by check mark whether the registrant (1) has filed all reports required to be filed by Section 13 or 15(d) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 during the preceding 12 months (or for such shorter period that the registrant was required to file such reports), and (2) has been subject to such filing requirements for the past 90 days. Yes ☑ No ☐

Indicate by check mark whether the registrant has submitted electronically every Interactive Data File required to be submitted pursuant to Rule 405 of Regulation S-T (§ 232.405 of this chapter) during the preceding 12 months (or for such shorter period that the registrant was required to submit such files). Yes ☑ No ☐

Indicate by check mark whether the registrant is a large accelerated filer, an accelerated filer, a non-accelerated filer, a smaller reporting company, or an emerging growth company. See the definitions of “large accelerated filer,” “accelerated filer,” “smaller reporting company,” and “emerging growth company” in Rule 12b-2 of the Exchange Act.

Large accelerated filer ☐ Accelerated filer ☑

Non-accelerated filer ☐ Smaller reporting company ☐

Emerging growth company ☐

If an emerging growth company, indicate by check mark if the registrant has elected not to use the extended transition period for complying with any new or revised financial accounting standards provided pursuant to Section 13(a) of the Exchange Act. ☐

Indicate by check mark whether the registrant has filed a report on and attestation to its management’s assessment of the effectiveness of its internal control over financial reporting under Section 404(b) of the Sarbanes-Oxley Act (15 U.S.C. 7262(b)) by the registered public accounting firm that prepared or issued its audit report. ☑

Indicate by check mark whether the registrant is a shell company (as defined in Rule 12b-2 of the Exchange Act). Yes ☐ No ☑

Aggregate market value of the voting and non-voting common equity held by non-affiliates (stockholders who are not directors or executive officers) of the Registrant, calculated using the closing price on June 30, 2021: Common Stock, par value $0.01 per share, $645.5 million.

Indicate by check mark whether the registrant has filed all documents and reports required to be filed by Section 12, 13 or 15(d) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 subsequent to the distribution of securities under a plan confirmed by a court. Yes ☑ No ☐

Number of shares outstanding of each of the Registrant’s classes of Common Stock, as of February 11, 2022: Common Stock, par value $0.01 per share, 133,607,136 shares outstanding.

DOCUMENTS INCORPORATED BY REFERENCE

Portions of the Company’s Proxy Statement to be filed with the Securities and Exchange Commission in connection with the Company’s 2022 Annual Meeting of Shareholders (the Company’s 2022 Proxy Statement) are incorporated by reference into Part III hereof. Other documents incorporated by reference in this report are listed in the Exhibit Index of this Form 10-K.

CAUTIONARY NOTICE REGARDING FORWARD-LOOKING STATEMENTS

This report includes statements of Peabody’s expectations, intentions, plans and beliefs that constitute “forward-looking statements” within the meaning of Section 27A of the Securities Act of 1933, as amended (the Securities Act), and Section 21E of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934, as amended (the Exchange Act), and are intended to come within the safe harbor protection provided by those sections. These statements relate to future events or Peabody’s future financial performance. The Company uses words such as “anticipate,” “believe,” “expect,” “may,” “forecast,” “project,” “should,” “estimate,” “plan,” “outlook,” “target,” “likely,” “will,” “to be” or other similar words to identify forward-looking statements.

Without limiting the foregoing, all statements relating to Peabody’s future operating results, anticipated capital expenditures, future cash flows and borrowings, and sources of funding are forward-looking statements and speak only as of the date of this report. These forward-looking statements are based on numerous assumptions that Peabody believes are reasonable, but are subject to a wide range of uncertainties and business risks, and actual results may differ materially from those discussed in these statements. These factors include but are not limited to those described in Part I, Item 1A. “Risk Factors.” Such factors are difficult to accurately predict and may be beyond the Company’s control.

When considering these forward-looking statements, you should keep in mind the cautionary statements in this document and in the Company’s other Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) filings. These forward-looking statements speak only as of the date on which such statements were made, and the Company undertakes no obligation to update these statements except as required by federal securities laws.

| | | | | | | | |

| Peabody Energy Corporation | 2021 Form 10-K | i |

TABLE OF CONTENTS

| | | | | | | | |

| Peabody Energy Corporation | 2021 Form 10-K | 1 |

| | | | | |

| Note: | The words “Peabody” or “the Company” as used in this report, refer to Peabody Energy Corporation or its applicable subsidiary or subsidiaries. Unless otherwise noted herein, disclosures in this Annual Report on Form 10-K relate only to the Company’s continuing operations. |

| When used in this filing, the term “ton” refers to short or net tons, equal to 2,000 pounds (907.18 kilograms), while “tonne” refers to metric tons, equal to 2,204.62 pounds (1,000 kilograms). |

PART I

Item 1. Business.

Overview

Peabody is a leading producer of metallurgical and thermal coal. At December 31, 2021, the Company owned interests in 17 active coal mining operations located in the United States (U.S.) and Australia, including a 50% equity interest in Middlemount Coal Pty Ltd. (Middlemount). In addition to its mining operations, the Company markets and brokers coal from other coal producers, both as principal and agent, and trades coal and freight-related contracts.

Segment and Geographic Information

As of December 31, 2021, Peabody reports its results of operations primarily through the following reportable segments: Seaborne Thermal Mining, Seaborne Metallurgical Mining, Powder River Basin Mining, Other U.S. Thermal Mining and Corporate and Other. Refer to Part II, Item 7. “Management’s Discussion and Analysis of Financial Condition and Results of Operations” for additional information regarding the Company’s segments. Note 24. “Segment and Geographic Information” to the accompanying consolidated financial statements is incorporated herein by reference and also contains segment and geographic financial information.

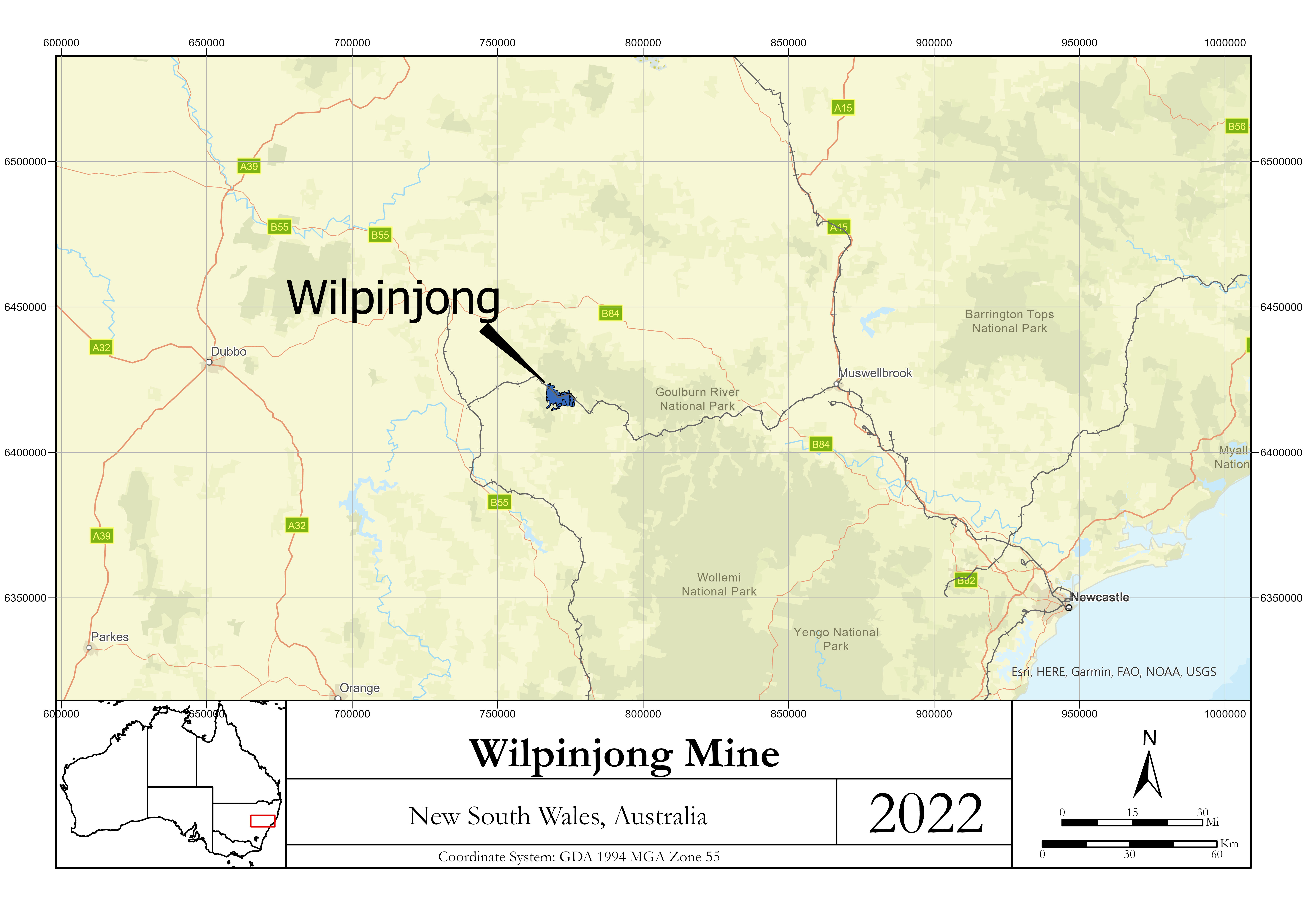

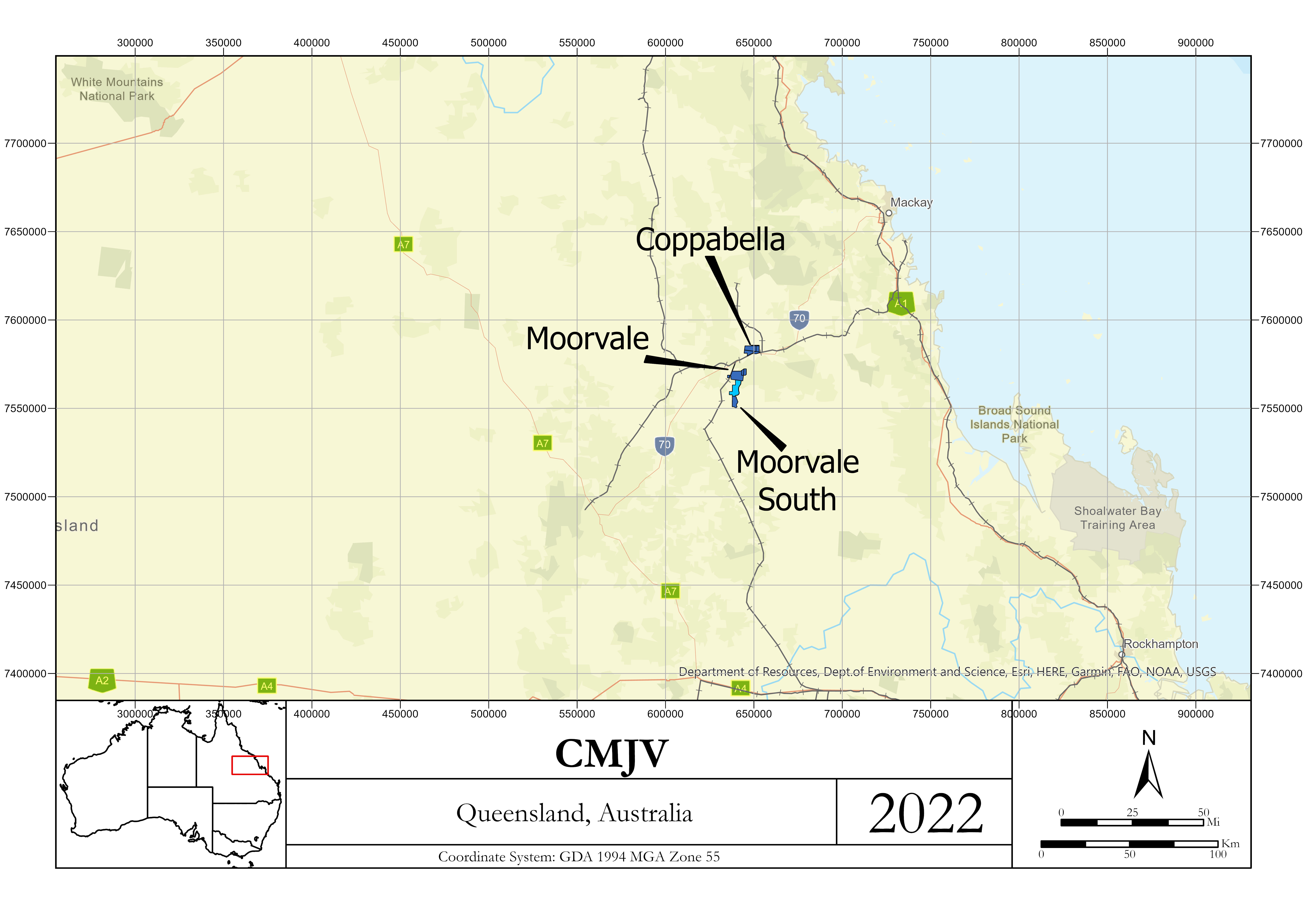

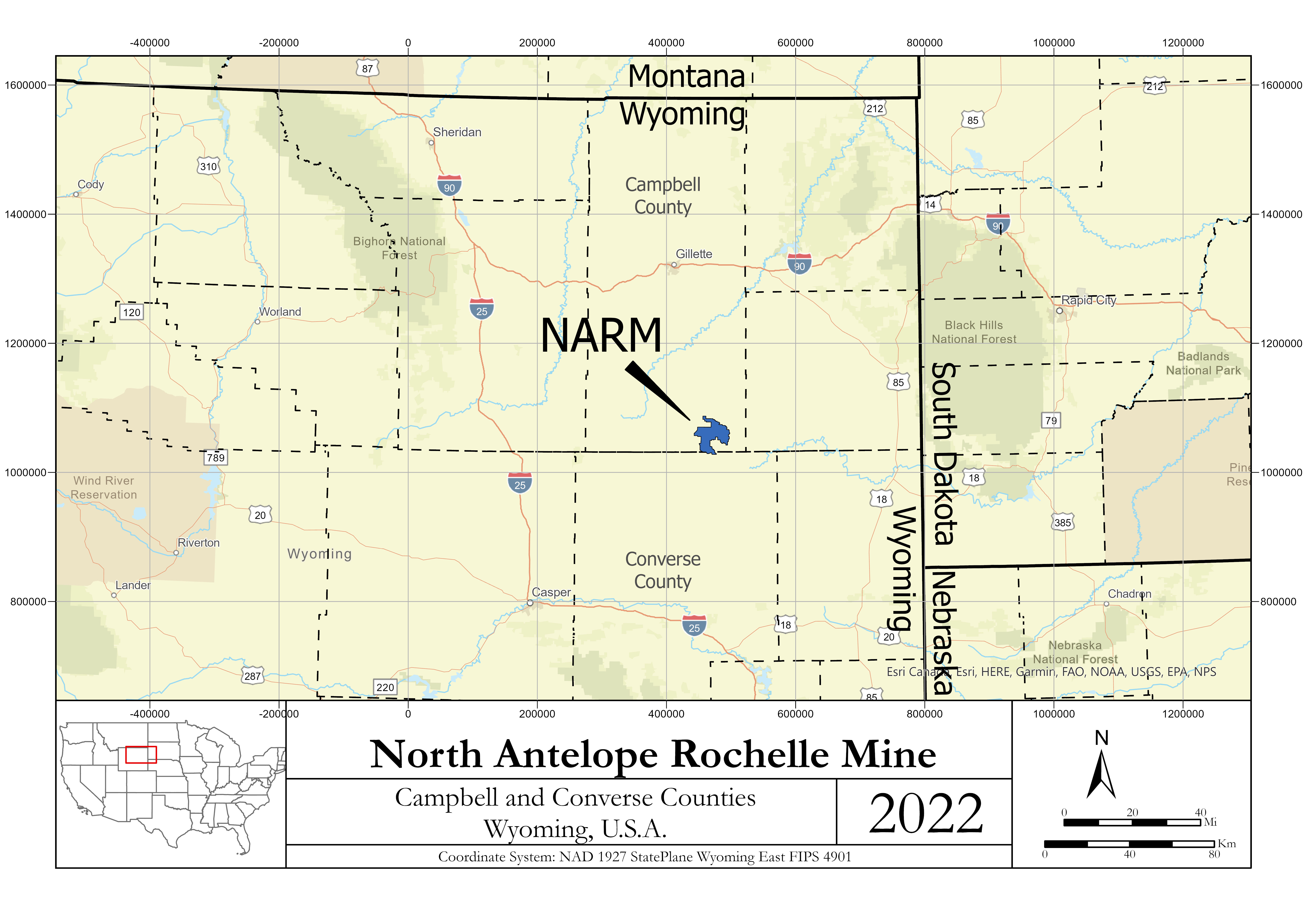

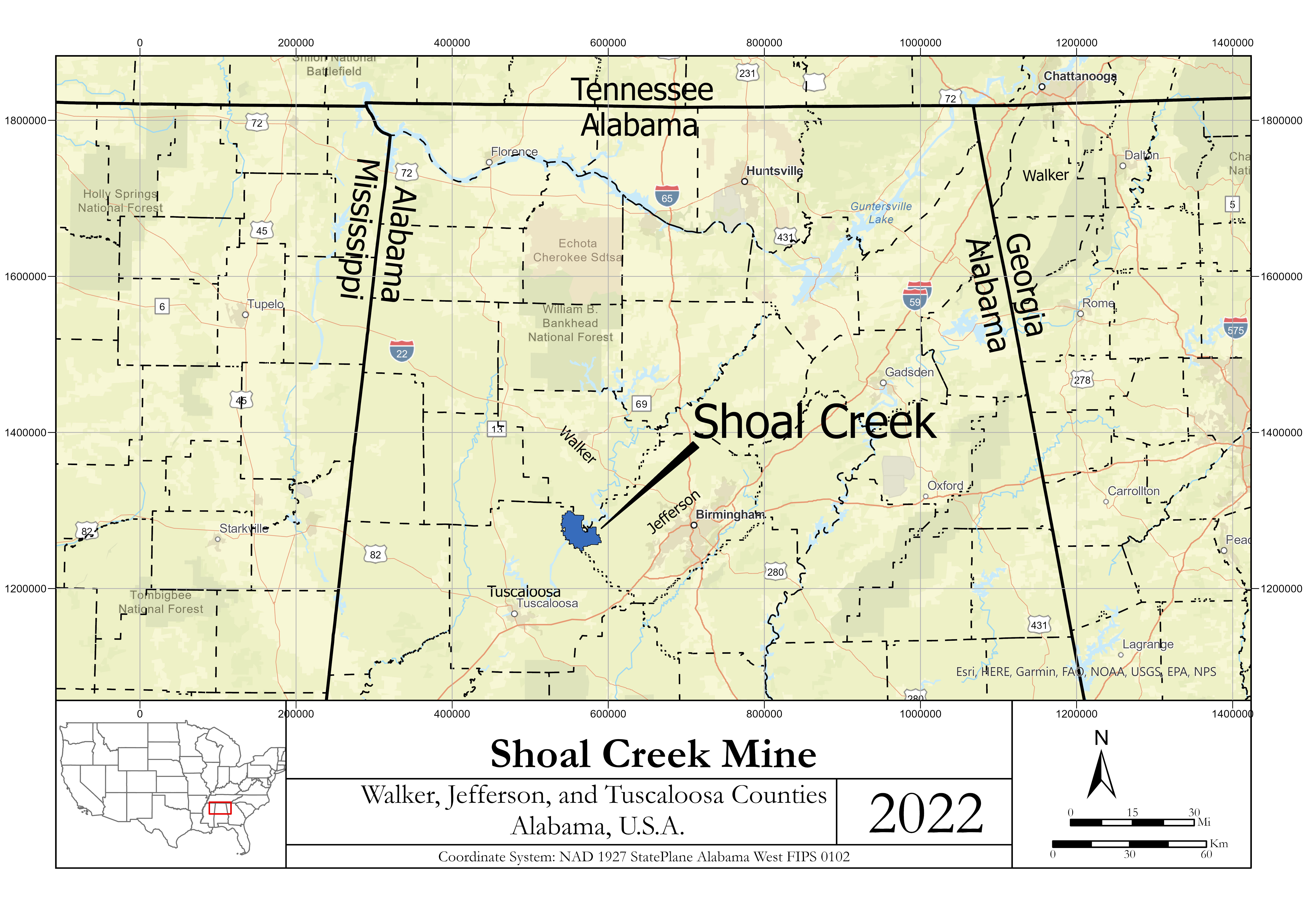

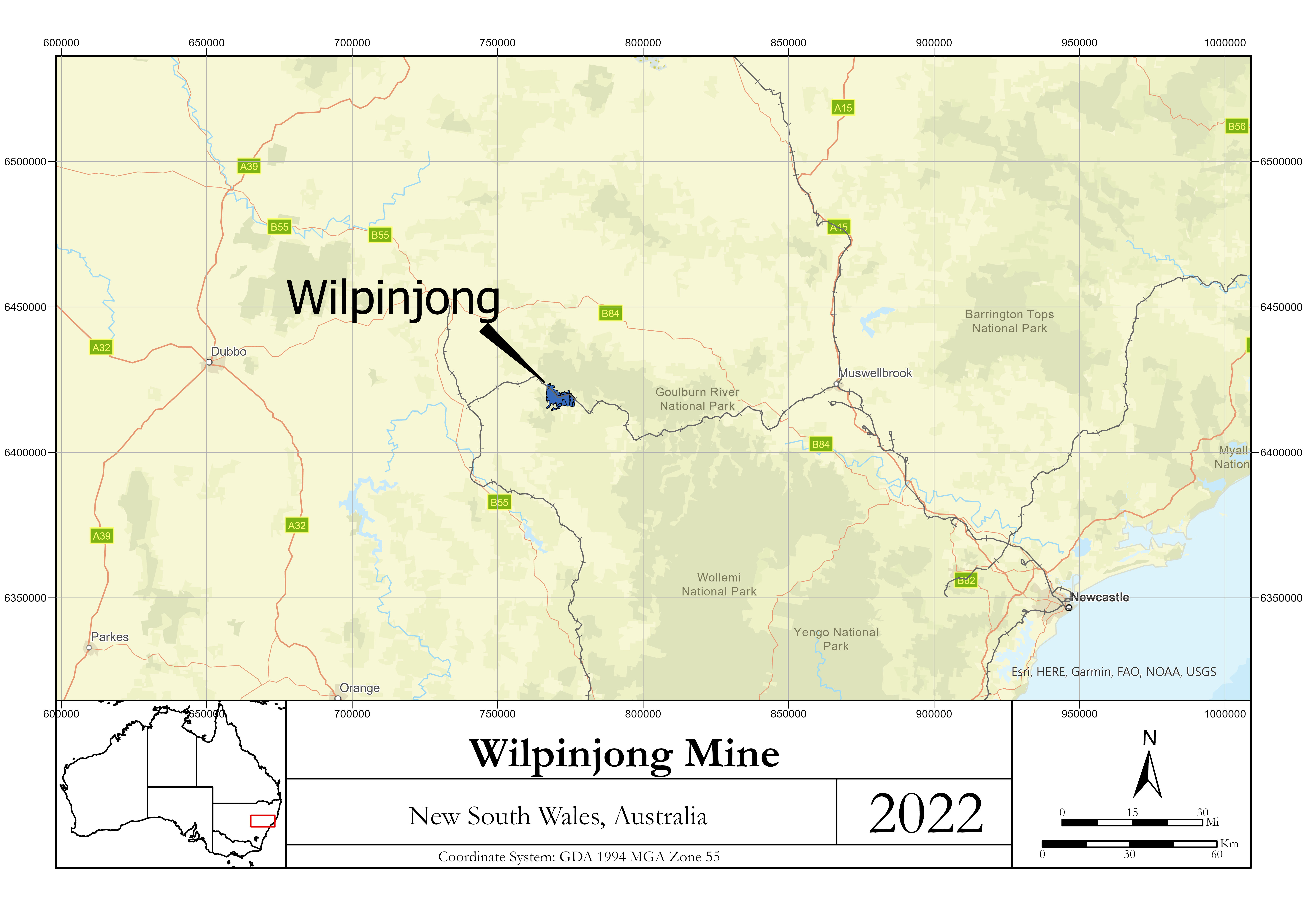

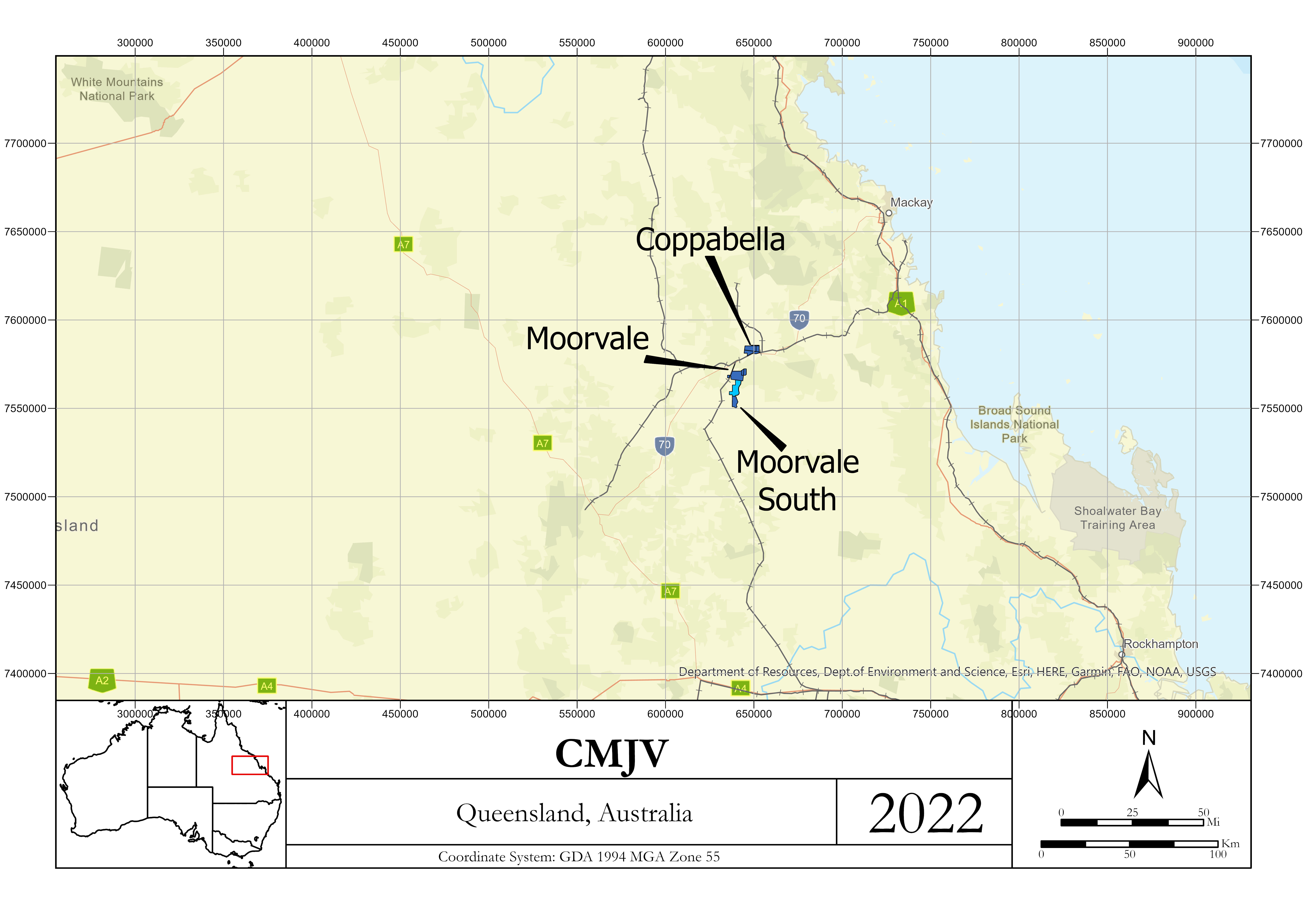

Mining Locations

The maps that follow display Peabody’s active mine locations as of December 31, 2021. Also shown are the primary ports that the Company uses for its coal exports and the Company’s corporate headquarters in St. Louis, Missouri.

U.S. Locations

| | | | | | | | |

| Peabody Energy Corporation | 2021 Form 10-K | 2 |

Australian Locations

| | | | | | | | |

| Peabody Energy Corporation | 2021 Form 10-K | 3 |

The table below summarizes information regarding the operating characteristics of each of the Company’s mines in the U.S. and Australia. The mines are listed within their respective mining segment in descending order, as determined by tons produced in 2021.

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | Production |

| Segment/Mining Complex | | Location | | Mine Type | | Mining Method | | Coal Type | | Primary Transport Method | | Processing

Plants | | Year Ended December 31, |

| | | | | | | 2021 | | 2020 | | 2019 |

| Seaborne Thermal Mining | | | | | | | | | | | | (Tons in millions) |

| Wilpinjong | | New South Wales | | S | | D, T/S | | T | | R, EV | | Yes | | 13.2 | | | 14.2 | | | 14.1 | |

Wambo Open-Cut (1) | | New South Wales | | S | | T/S | | T | | R, EV | | Yes | | 2.4 | | | 4.0 | | | 3.4 | |

Wambo Underground (2) | | New South Wales | | U | | LW | | T, C | | R, EV | | Yes | | 1.4 | | | 1.5 | | | 2.2 | |

| Seaborne Metallurgical Mining | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

Coppabella (3) | | Queensland | | S | | DL, D, T/S | | P | | R, EV | | Yes | | 2.1 | | | 2.2 | | | 2.4 | |

Moorvale (3) | | Queensland | | S | | D, T/S | | C, P, T | | R, EV | | Yes | | 1.3 | | | 1.2 | | | 1.7 | |

Metropolitan (4) | | New South Wales | | U | | LW | | C, P, T | | R, EV | | Yes | | 1.0 | | | 1.0 | | | 1.5 | |

Shoal Creek (5) | | Alabama | | U | | LW | | C | | B, EV | | Yes | | 0.1 | | | 0.6 | | | 1.9 | |

Millennium (6) | | Queensland | | S | | HW | | C, P | | R, EV | | No | | — | | | 0.1 | | | 0.6 | |

Middlemount (7) | | Queensland | | S | | D, T/S | | C, P | | R, EV | | Yes | | — | | | — | | | — | |

| Powder River Basin Mining | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| North Antelope Rochelle | | Wyoming | | S | | DL, D, T/S | | T | | R | | No | | 62.8 | | | 66.1 | | | 85.3 | |

| Caballo | | Wyoming | | S | | D, T/S | | T | | R | | No | | 13.9 | | | 11.6 | | | 12.6 | |

| Rawhide | | Wyoming | | S | | D, T/S | | T | | R | | No | | 11.6 | | | 9.5 | | | 10.1 | |

| Other U.S. Thermal Mining | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| Bear Run | | Indiana | | S | | DL, D, T/S | | T | | Tr, R | | Yes | | 6.0 | | | 5.2 | | | 6.8 | |

| El Segundo/Lee Ranch | | New Mexico | | S | | DL, D, T/S | | T | | R | | No | | 3.7 | | | 4.6 | | | 5.5 | |

| Wild Boar | | Indiana | | S | | D, T/S, HW | | T | | Tr, R, R/B, T/B | | Yes | | 2.4 | | | 2.0 | | | 2.5 | |

| Gateway North | | Illinois | | U | | CM | | T | | Tr, R, R/B, T/B | | Yes | | 1.8 | | | 1.8 | | | 3.0 | |

| Twentymile | | Colorado | | U | | LW | | T | | R, Tr | | Yes | | 1.7 | | | 1.2 | | | 2.6 | |

| Francisco Underground | | Indiana | | U | | CM | | T | | R | | Yes | | 1.5 | | | 1.6 | | | 2.0 | |

Somerville Central (6) | | Indiana | | S | | DL, D, T/S | | T | | R, R/B, T/B, T/R | | No | | — | | | 0.4 | | | 1.2 | |

Kayenta (8) | | Arizona | | S | | DL, T/S | | T | | R | | No | | — | | | — | | | 3.8 | |

Wildcat Hills Underground (8) | | Illinois | | U | | CM | | T | | T/B | | No | | — | | | — | | | 1.4 | |

Cottage Grove (8) | | Illinois | | S | | D, T/S | | T | | T/B | | No | | — | | | — | | | 0.1 | |

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| Legend: | | | |

| S | Surface Mine | | B | Barge |

| U | Underground Mine | | Tr | Truck |

| HW | Highwall Miner | | R/B | Rail to Barge |

| DL | Dragline | | T/B | Truck to Barge |

| D | Dozer/Casting | | T/R | Truck to Rail |

| T/S | Truck and Shovel | | EV | Export Vessel |

| LW | Longwall | | T | Thermal/Steam |

| CM | Continuous Miner | | C | Coking |

| R | Rail | | P | Pulverized Coal Injection |

(1)In December 2020, the United Wambo Joint Venture, an unincorporated joint venture between Peabody and Glencore plc, began joint production. The tons shown reflect Peabody’s proportionate share throughout the years. The Company’s 50% joint venture interest is subject to an outside non-controlling ownership interest.

(2)Majority-owned mine in which there is an outside non-controlling ownership interest.

(3)Peabody owns a 73.3% undivided interest in an unincorporated joint venture that owns the Coppabella and Moorvale mines. The tons shown reflect its share.

(4)The mine was idled in the fourth quarter of 2020. The mine restarted production in the second quarter of 2021.

(5)The mine was idled in the fourth quarter of 2020. The mine restarted production in November 2021.

(6)The mine ceased production during 2020.

(7)Peabody owns a 50% equity interest in Middlemount, which owns the Middlemount Mine. Because Middlemount is accounted for as an unconsolidated equity affiliate, the table above excludes tons produced from that mine, which totaled 2.0 million, 1.6 million and 1.4 million tons, respectively (on a 50% basis).

(8)The mine ceased production in 2019.

Refer to the Reserves and Resources tables within Item 2. “Properties,” which is incorporated by reference herein, for additional information regarding coal reserves and resources, and product characteristics associated with each mine.

| | | | | | | | |

| Peabody Energy Corporation | 2021 Form 10-K | 4 |

Coal Supply Agreements

Customers. Peabody’s coal supply agreements are primarily with electricity generators, industrial facilities and steel manufacturers. Most of the Company’s sales from its mining operations are made under long-term coal supply agreements (those with initial terms of one year or longer and which often include price reopener and/or extension provisions). A smaller portion of the Company’s sales from its mining operations are made under contracts with terms of less than one year, including sales made on a spot basis. Sales under long-term coal supply agreements comprised approximately 84%, 89% and 88% of the Company’s worldwide sales from its mining operations (by volume) for the years ended December 31, 2021, 2020 and 2019, respectively.

For the year ended December 31, 2021, Peabody derived 26% of its revenues from coal supply agreements from its five largest customers. Those five customers were supplied primarily from 17 coal supply agreements (excluding trading and brokerage transactions) expiring at various times from 2022 to 2026. Peabody’s largest customer in 2021 contributed revenue of approximately $258 million, or approximately 8% of Peabody’s total revenues from coal supply agreements, and has contracts expiring at various times from 2022 to 2025.

Backlog. Peabody’s sales backlog, which includes coal supply agreements subject to price reopener and/or extension provisions, was approximately 283 million and 264 million tons of coal as of January 1, 2022 and 2021, respectively. Contracts in backlog have remaining terms ranging from one to nine years and represent approximately two years of production based on the Company’s 2021 production volume of 126.9 million tons. Approximately 57% of its backlog is expected to be filled beyond 2022.

Seaborne Mining Operations. Revenues from Peabody’s Seaborne Thermal Mining and Seaborne Metallurgical Mining segments represented approximately 50%, 42% and 45% of its total revenues from coal supply agreements for the years ended December 31, 2021, 2020 and 2019, respectively, during which periods the coal mining activities of those segments contributed respective amounts of 18%, 19% and 17% of its sales volumes from mining operations. The Company’s production is primarily sold into the seaborne thermal and metallurgical markets, with a majority of those sales executed through annual and multi-year international coal supply agreements that contain provisions requiring both parties to renegotiate pricing periodically. Industry commercial practice, and Peabody’s typical practice, is to negotiate pricing for seaborne thermal coal contracts on an annual, spot or index basis and seaborne metallurgical coal contracts on a bi-annual, quarterly, spot or index basis. For its seaborne mining operations, the portion of sales volume under contracts with a duration of less than one year represented 45% in 2021.

U.S. Thermal Mining Operations. Revenues from Peabody’s Powder River Basin Mining and Other U.S. Thermal Mining segments, in aggregate, represented approximately 50%, 58% and 55% of its revenues from coal supply agreements for the years ended December 31, 2021, 2020 and 2019, respectively, during which periods the coal mining activities of those segments contributed respective aggregate amounts of approximately 82%, 81% and 83% of its sales volumes from mining operations. The Company expects to continue selling a significant portion of coal production from its U.S. thermal mining segments under existing long-term supply agreements. Certain customers utilize long-term sales agreements in recognition of the importance of reliability, service and predictable coal prices to their operations. The terms of coal supply agreements result from competitive bidding and extensive negotiations with customers. Consequently, the terms of those agreements may vary significantly in many respects, including price adjustment features, price reopener terms, coal quality requirements, quantity parameters, permitted sources of supply, treatment of environmental constraints, extension options, force majeure and termination and assignment provisions. Peabody’s approach is to selectively renew, or enter into new, long-term supply agreements when it can do so at prices and terms and conditions it believes are favorable. However, recent trends indicate that customers may be less likely to enter into long-term supply agreements prospectively, driven by the reduced utilization of plants and plant retirements, fluidity of natural gas pricing and the increased use of renewable energy sources.

Transportation