UNITED STATES

SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION

WASHINGTON, DC 20549

Form

ANNUAL REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 | ||

For the fiscal year ended | ||

or | ||

TRANSITION REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 |

Commission file number:

(Exact name of registrant as specified in its charter)

(State or other jurisdiction | (I.R.S. Employer |

(Address of principal executive offices) | (Zip code) |

Registrant’s telephone number, including area code: (

Securities registered pursuant to Section 12(b) of the Act:

Title of Each Class | Trading Symbol | Name of Each Exchange on Which Registered |

Securities registered pursuant to Section 12(g) of the Act: None

Indicate by check mark if the registrant is a well-known seasoned issuer, as defined in Rule 405 of the Securities Act.

Indicate by check mark if the registrant is not required to file reports pursuant to Section 13 or Section 15(d) of the Act. Yes ☐

Indicate by check mark whether the registrant: (1) has filed all reports required to be filed by Section 13 or 15(d) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 during the preceding 12 months (or for such shorter period that the registrant was required to file such reports), and (2) has been subject to such filing requirements for the past 90 days.

Indicate by check mark whether the registrant has submitted electronically every Interactive Data File required to be submitted pursuant to Rule 405 of Regulation S-T (§232.405 of this chapter) during the preceding 12 months (or for such shorter period that the registrant was required to submit such files).

Indicate by check mark whether the registrant is a large accelerated filer, an accelerated filer, a non-accelerated filer, smaller reporting company, or an emerging growth company. See the definitions of “large accelerated filer,” “accelerated filer,” “smaller reporting company,” and “emerging growth company” in Rule 12b-2 of the Exchange Act.

☒ | Accelerated filer | ☐ | |

Non-accelerated filer | ☐ | Smaller reporting company | |

Emerging growth company |

If an emerging growth company, indicate by check mark if the registrant has elected not to use the extended transition period for complying with any new or revised financial accounting standards provided pursuant to Section 13(a) of the Exchange Act. ☐

Indicate by check mark whether the registrant has filed a report on and attestation to its management's assessment of the effectiveness of its internal control over financial reporting under Section 404(b) of the Sarbanes-Oxley Act (15 U.S.C. 7262(b)) by the registered public accounting firm that prepared or issued its audit report.

If securities are registered pursuant to Section 12(b) of the Act, indicate by check mark whether the financial statements of the registrant included in the filing reflect the correction of an error to previously issued financial statements.

Indicate by check mark whether any of those error corrections are restatements that required a recovery analysis of incentive-based compensation received by any of the registrant’s executive officers during the relevant recovery period pursuant to §240.10D-1(b). ☐

Indicate by check mark whether the registrant is a shell company (as defined in Rule 12b-2 of the Act). Yes

The aggregate market value of the voting stock held by non-affiliates of the registrant (excluding outstanding shares beneficially owned by directors, officers, other affiliates and treasury shares) as of June 30, 2023 was approximately $

At February 1, 2024 there were

DOCUMENTS INCORPORATED BY REFERENCE

Portions of the registrant’s definitive proxy statement to be filed with the Securities and Exchange Commission in connection with the 2023 annual stockholders’ meeting are incorporated by reference into Part III of this Form 10-K.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

2

If you are not familiar with any of the mining terms used in this report, we have provided explanations of many of them under the caption “Glossary of Selected Mining Terms” on page 38 of this report. Unless the context otherwise requires, all references in this report to “Arch,” the Company,” “we,” “us,” or “our” are to Arch Resources, Inc. and its subsidiaries.

CAUTIONARY STATEMENTS REGARDING FORWARD-LOOKING INFORMATION

This report contains forward-looking statements, within the meaning of Section 27A of the Securities Act of 1933, as amended, and Section 21E of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934, as amended, such as our expected future business and financial performance, and are intended to come within the safe harbor protections provided by those sections. The words “anticipates,” “believes,” “could,” “estimates,” “expects,” “intends,” “may,” “plans,” “predicts,” “projects,” “seeks,” “should,” “will” or other comparable words and phrases identify forward-looking statements, which speak only as of the date of this report. Forward-looking statements by their nature address matters that are, to different degrees, uncertain. Actual results may vary significantly from those anticipated due to many factors, including:

| ● | loss of availability, reliability and cost-effectiveness of transportation facilities and fluctuations in transportation costs; |

| ● | operating risks beyond our control, including risks related to mining conditions, mining, processing and plant equipment failures or maintenance problems, weather and natural disasters, the unavailability of raw materials, equipment or other critical supplies, mining accidents, and other inherent risks of coal mining that are beyond our control; |

| ● | inflationary pressures on and availability and price of mining and other industrial supplies; |

| ● | changes in coal prices, which may be caused by numerous factors beyond our control, including changes in the domestic and foreign supply of and demand for coal and the domestic and foreign demand for steel and electricity; |

| ● | volatile economic and market conditions; |

| ● | the effects of foreign and domestic trade policies, actions or disputes on the level of trade among the countries and regions in which we operate, the competitiveness of our exports, or our ability to export; |

| ● | the effects of significant foreign conflicts; |

| ● | the loss of, or significant reduction in, purchases by our largest customers; |

| ● | our relationships with, and other conditions affecting our customers and our ability to collect payments from our customers; |

| ● | risks related to our international growth; |

| ● | competition, both within our industry and with producers of competing energy sources, including the effects from any current or future legislation or regulations designed to support, promote or mandate renewable energy sources; |

| ● | alternative steel production technologies that may reduce demand for our coal; |

| ● | our ability to secure new coal supply arrangements or to renew existing coal supply arrangements; |

| ● | cyber-attacks or other security breaches that disrupt our operations, or that result in the unauthorized release of proprietary, confidential or personally identifiable information; |

| ● | our ability to acquire or develop coal reserves in an economically feasible manner; |

3

| ● | inaccuracies in our estimates of our coal reserves; |

| ● | defects in title or the loss of a leasehold interest; |

| ● | the availability and cost of surety bonds; including potential collateral requirements; |

| ● | We may not have adequate insurance coverage for some business risks; |

| ● | disruptions in the supply of coal from third parties; |

| ● | Decreases in the coal consumption of electric power generators could result in less demand and lower prices for thermal coal; |

| ● | our ability to pay dividends or repurchase shares of our common stock according to our announced intent or at all; |

| ● | the loss of key personnel or the failure to attract additional qualified personnel and the availability of skilled employees and other workforce factors; |

| ● | public health emergencies, such as pandemics or epidemics, could have an adverse effect on our business; |

| ● | existing and future legislation and regulations affecting both our coal mining operations and our customers’ coal usage, governmental policies and taxes, including those aimed at reducing emissions of elements such as mercury, sulfur dioxides, nitrogen oxides, particulate matter or greenhouse gases; |

| ● | increased pressure from political and regulatory authorities, along with environmental and climate change activist groups, and lending and investment policies adopted by financial institutions and insurance companies to address concerns about the environmental impacts of coal combustion; |

| ● | increased attention to environmental, social or governance matters (“ESG”); |

| ● | our ability to obtain or renew various permits necessary for our mining operations; |

| ● | risks related to regulatory agencies ordering certain of our mines to be temporarily or permanently closed under certain circumstances; |

| ● | risks related to extensive environmental regulations that impose significant costs on our mining operations, and could result in litigation or material liabilities; |

| ● | the accuracy of our estimates of reclamation and other mine closure obligations; |

| ● | the existence of hazardous substances or other environmental contamination on property owned or used by us; |

| ● | risks related to tax legislation and our ability to use net operating losses and certain tax credits; and |

| ● | other factors, including those discussed in “Legal Proceedings,” set forth in Item 3 of this report and “Risk Factors,” set forth in Item 1A of this report. |

All forward-looking statements in this report, as well as all other written and oral forward-looking statements attributable to us or persons acting on our behalf, are expressly qualified in their entirety by the cautionary statements contained in this section and elsewhere in this report. These factors are not necessarily all of the important factors that could affect us. These risks and uncertainties, as well as other risks of which we are not aware or which we currently do not believe to be material, may cause our actual future results to be materially different than those expressed in our forward-looking statements. These forward-looking statements speak only as of the date on which such statements were

4

made, and we do not undertake to update our forward-looking statements, whether as a result of new information, future events or otherwise, except as may be required by the federal securities laws.

Additionally, our discussions of certain ESG matters and issues herein are developed with various standards and frameworks (including standards for the measurement of underlying data), and the interests of various stakeholders. As such, such discussions may not necessarily be “material” under the federal securities laws for SEC reporting purposes. Furthermore, many of our disclosures regarding ESG matters are subject to methodological considerations or information, including from third parties, that is still evolving and subject to change. For example, our disclosures based on any standards may change due to revisions in framework requirements, availability of information, changes in our business or applicable government policies, or other factors, some of which may be beyond our control.

5

PART I

ITEM 1. BUSINESS

Introduction

We are one of the world’s largest coal producers and a premier producer of metallurgical coal. For the year ended December 31, 2023, we sold approximately 75 million tons of coal, including approximately 0.1 million tons of coal we purchased from third parties. We sell substantially all of our coal to steel mills, power plants and industrial facilities. At December 31, 2023, we operated seven active mines located in three of the major coal-producing regions of the United States. The locations of our mines and access to export facilities enable us to ship coal worldwide. We incorporate by reference the information about the geographical breakdown of our coal sales for the respective periods covered within this report contained in Note 20, “Risk Concentrations” to the Consolidated Financial Statements.

Business Strategy

We are a leading United States producer of metallurgical products for the global steel industry, and the leading supplier of premium High-Vol A metallurgical coal globally. We operate four large, modern metallurgical mines that consistently achieve high standards for both mine safety and environmental stewardship. Leer and Leer South longwall mines anchor our large-scale, first quartile metallurgical franchise. The Leer franchise consistently ranks among the lowest cost U.S. metallurgical mines and produces a product quality that is recognized and sought-after worldwide. The Leer and Leer South operations are complemented by the Beckley and Mountain Laurel continuous miner mines, which in aggregate provide us with a full suite of high-quality metallurgical products for sale into the global metallurgical market.

Arch and its subsidiaries also operate thermal mines in the Powder River Basin and Colorado that produce thermal coal for sale into international and domestic markets. In Colorado, our West Elk mine produces a high-quality thermal product that can compete effectively in seaborne markets, where thermal coal demand remains robust. In addition, West Elk supplies a sizeable North American industrial customer base that we believe will continue to rely significantly on thermal coal, which can be highly advantageous for specific industrial applications. In the Powder River Basin, most of our production is sold to U.S. power generators, who are systematically shifting their generating capacity to other, non-coal fuel and energy sources. In keeping with this shift and the ongoing decline in domestic demand for thermal coal, Arch is managing the shrinking of its operating footprint in an economically and socially responsible manner, taking into careful consideration the needs of its thermal employee base, the communities in which we operate, and the needs of our thermal power customers as well as consumers of power generation generally. We remain confident that our Powder River Basin mines can continue to provide significant, incremental cash flow to complement the strong cash-generating capabilities of our core metallurgical franchise in the near to intermediate term, while self-funding their own closure obligations over the longer term.

We believe that our long-term success depends upon achieving excellence in mine safety and environmental stewardship; conducting business in an ethical and transparent manner; investing in our people and the communities in which we operate; and demonstrating strong corporate governance. With our strategic shift towards metallurgical products – which are an essential input in the production of new steel – we have aligned our value proposition to reflect the world’s intensifying focus on sustainability and the construction of a new, steel-intensive, low-carbon economy. We were the first – and remain the only – U.S. metallurgical coal producer to join Responsible Steel, the steel industry’s global multi-stakeholder standard and certification initiative. In the fourth quarter of 2023, our Leer mine achieved Level A verification for all protocols comprising the Towards Sustainable Mining (TSM) Initiative, which we believe further enhances our standing as a supplier of choice to increasingly sustainability-focused global steelmakers.

We are a demonstrated leader in mine safety, with an average lost-time incident rate during the past five years that is nearly 2.5 times better than the industry average. Our subsidiaries have won more than 40 national and state safety awards in the past five years.

In the environmental arena, our subsidiaries received zero notices of violation (NOV) in 2023 and 2021 while receiving one NOV in 2022. Arch has averaged fewer than one NOV per year over the past five years, versus an average of approximately 15 annually by 10 other major U.S. coal producers. In the area of water management, there have been zero exceedances for a 100 percent compliance record for the third year in a row.

6

Coal Characteristics

End users generally characterize coal as thermal coal or metallurgical coal. Heat value, sulfur, ash, moisture content, and volatility, in the case of metallurgical coal, are important variables in the marketing and transportation of coal. These characteristics help producers determine the best end use of a particular type of coal. The following is a description of these general coal characteristics:

Heat Value. In general, the carbon content of coal supplies most of its heating value, but other factors also influence the amount of energy it contains per unit of weight. The heat value of coal is commonly measured in Btus. Coal is generally classified into four categories, lignite, subbituminous, bituminous and anthracite, reflecting the progressive response of individual deposits of coal to increasing heat and pressure. Anthracite is coal with the highest carbon content and, therefore, the highest heat value, nearing 15,000 Btus per pound. Bituminous coal, used primarily to generate electricity and to make coke for the steel industry, has a heat value ranging between 10,500 and 15,500 Btus per pound. Subbituminous coal ranges from 8,300 to 13,000 Btus per pound and is generally used for electric power generation. Lignite coal is a geologically young coal which has the lowest carbon content and a heat value ranging between 4,000 and 8,300 Btus per pound.

Sulfur Content. Federal and state environmental regulations, including regulations that limit the amount of sulfur dioxide that may be emitted as a result of combustion, have affected and may continue to affect the demand for certain types of coal. The sulfur content of coal can vary from seam to seam and within a single seam. The chemical composition and concentration of sulfur in coal affects the amount of sulfur dioxide produced in combustion. Coal-fueled power plants can comply with sulfur dioxide emission regulations by burning coal with low sulfur content, blending coals with various sulfur contents, purchasing emission allowances on the open market and/or using sulfur dioxide emission reduction technology.

Ash. Ash is the inorganic material remaining after the combustion of coal. As with sulfur, ash content varies from seam to seam. Ash content is an important characteristic of coal because it impacts boiler performance and electric generating plants must handle and dispose of ash following combustion. The composition of the ash, including the proportion of sodium oxide and fusion temperature, is also an important characteristic of coal, as it helps to determine the suitability of the coal to end users. The absence of ash is also important to the process by which metallurgical coal is transformed into coke for use in steel production.

Moisture. Moisture content of coal varies by the type of coal, the region where it is mined and the location of the coal within a seam. In general, high moisture content decreases the heat value and increases the weight of the coal, thereby making it more expensive to transport. Moisture content in coal, on an as-sold basis, can range from approximately 2% to over 30% of the coal’s weight.

Other. Users of metallurgical coal measure certain other characteristics, including fluidity, volatility, and swelling capacity to assess the strength of coke produced from a given coal or the amount of coke that certain types of coal will yield. These characteristics are important elements in determining the value of the metallurgical coal we produce and market.

Industry Overview

Background. Coal is mined globally using various methods of surface and underground recovery. Coal is primarily used for steel production and electric power generation, but it is also used for certain industrial processes such as cement production. Coal is a globally marketed commodity and can be transported to demand centers by ocean-going vessels, barge, rail, truck or conveyor belt.

In 2023, world coal production further recovered from the COVID-19 pandemic related supply and demand disruptions experienced in 2020. An expansionary economic environment was supportive of coal fundamentals in 2023. Based on preliminary industry data and internal estimates, we believe world coal production increased around 2% in 2023 to approximately 8.9 billion metric tons; this likely represents an all-time for yearly world coal production after having increased around 8% in 2022.

7

China is the largest producer of coal in the world accounting for over 50% of total production. According to available data from the Chinese National Bureau of Statistics and Estimates, China produced around 4.7 billion metric tons of coal in 2023. Other major coal producing countries are India, Indonesia, the United States, Australia, Russia, South Africa and Colombia. India, the world’s second biggest coal producer, could reach 1 billion metric tons of production in 2024. In 2023, U.S. coal production decreased by approximately 2% to 528 million metric tons, after increasing around 3% in 2022 to around 540 million metric tons mainly due to lower demand for power generation. U.S. coal production has decreased by roughly 50% in the past decade as coal-fired generation demand has continued to decrease. The U.S. is now the fourth largest producer after being surpassed by India and Indonesia in the past decade.

Steel is produced via two main methods: basic oxygen furnace (BOF) and electric arc furnace (EAF). EAF steelmaking produces steel by using an electrical current to melt scrap steel, while BOF steelmaking relies on coke and iron ore as key inputs to produce pig iron, which is then converted into steel. Metallurgical coal is a key part of the BOF process as it is used to make coke.

The main steel producing countries are China, India, Japan, United States, Russia, South Korea, Turkey, Germany, Brazil, and Italy. Approximately 72% of global steel is produced via the BOF steelmaking process, while in the United States, BOF accounts for around 31% of steel production. Arch sells high-quality metallurgical coal products that are essential inputs for BOF steel production worldwide. Our focus is to be a premier low-cost, metallurgical coal supplier to the global steel industry.

In 2023, world steel production is expected to be little changed from 2022 due to ongoing global recessionary fears, inflationary pressures and the Ukraine-Russia war. The World Steel Association forecasts steel demand to grow around 2% globally in 2023; however, the demand growth will not be balanced. Steel demand growth in some key regions, including Europe, South America, Africa and the Middle East, will be negative, according to World Steel Association forecasts. Chinese steel production was flat in 2023, as the government implemented production controls.

Global trade of metallurgical coal was also affected by the pandemic and has slowly recovered. We estimate metallurgical coal import-export trade flows improved slightly in 2023 from 2022 levels. A full restoration of trade volumes back to pre-pandemic levels could take place in 2024; however, certain factors continue to affect the industry, including weather, geological issues, workforce absenteeism, supply chain constraints, transportation reliability and lingering effects from the COVID-19 pandemic, including responses thereto. The primary nations that supply seaborne metallurgical coal to the global steel markets are Australia, the United States, Canada, and Russia.

Australia is the largest metallurgical coal exporter and the second largest thermal coal exporter in the world. Towards the end of 2020, China implemented a ban on all coal imports from Australia. This ban imposed by the key importer of coal on the key exporter of coal rearranged historical global trade patterns. Although the ban on Australian coal was lifted in 2023, it was in place long enough to further open the Chinese markets to United States coal suppliers. In 2023, Australian exports of metallurgical to China were limited compared to recent historical averages. Australian metallurgical coal exports are expected to have fallen in 2023, reaching the lowest level in 11 years, based on preliminary trade data. Additionally, the regulatory environment in Australia has become more restrictive for coal mining, including the recently enacted increase in royalty rates within Queensland. These actions have limited additional investment in the coal mining industry.

We rank among the largest metallurgical coal producers in the United States. Based on internal estimates, we produced around 11% of total U.S. metallurgical coal supply, which was estimated to be around 75 million tons in 2023. Our metallurgical coal was sold to five North American customers and exported to 34 customers overseas in 11 countries in 2023.

All of our metallurgical coal is produced at operations in West Virginia. Approximately 50% of the metallurgical coal produced in the United States is produced in West Virginia. Carbon content, volatility, fluidity, coke strength after reaction (CSR), and other chemical and physical properties are among critical characteristics for metallurgical coal.

8

We produce coal used for electric power generation (thermal) and industrial facilities from our mines located in Wyoming and Colorado. The European energy crisis, which was exacerbated by the Ukraine-Russia war, contributed to strong demand for our thermal coal products from international buyers in 2022, although the demand growth in 2023 was subdued. The European Union, which has traditionally been a major market for Russian coals, imposed a ban on Russian coals as of August 2022. Limited global investments in thermal coal supply, weather events, a lack of qualified labor availability, and other factors limited the supply response, which resulted in record prices for domestic and international markets in 2022.

Much of our domestic coal is sold at the mine where title and risk of loss transfer to the customer as coal is loaded into the railcar or truck. Customers are generally responsible for transportation - typically using third party carriers. There are, however, some agreements where we retain responsibility for the coal during delivery to the customer site or intermediate terminal. Our export coals usually change title and risk of loss as the coal is loaded on a vessel. Normally we contract for transportation services from the mine to the ocean loading port. On occasion, we retain title to the coal to the ocean receiving port.

In 2023, approximately 88% of our coal volumes were sold as thermal products with the remaining 12% sold as metallurgical products. However, due to the significantly higher value and selling price of our metallurgical coals compared to thermal coals, our metallurgical segment contributed around 60% of our total sales revenue in 2023.

We seek to establish direct long-term relationships with customers through exemplary customer service while operating safe and environmentally responsible mines. The commercial environment in which we operate is very competitive. We compete with domestic and international coal producers, traders or brokers, and non-coal based power producers, as well as with electric arc-based steel producers. We compete using price, coal quality, transportation, optionality, customer administration, reputation, and reliability.

We have an experienced and knowledgeable sales, marketing, and logistics group. This group is dedicated to meeting customer needs, coordinating transportation, and managing risk.

Coal prices are tied to competing fuel sources as well as supply and demand patterns, which are influenced by many uncontrollable factors. For power generation, the price of coal is affected by the relative supply and demand of competitive coal, transportation, availability, weather, competing power generation fuels particularly natural gas, governmental subsidies of alternate energy sources, regulations and economic conditions. For metallurgical coal, the price of coal is affected by the supply and demand of competitive coal, transportation, the price of steel, the price of scrap, demand for steel, transportation rates, strength of the U.S. dollar, regulations, international trade disputes and economic conditions.

U.S. Coal Production. The United States is among the largest coal producers in the world. According to the U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA), there are over 250 billion short tons of recoverable coal reserves in the United States. Current domestic recoverable coal reserves could supply the coal-fired generation fleet for the next 500 years, based on current demand.

The EIA subdivides United States coal production into three major areas: Western Region, Appalachia, and Interior Region. According to the preliminary information from EIA, total U.S. coal production decreased by an estimated 13 million short tons in 2023, to around 582 million short tons.

The Western Region includes the Powder River Basin and the Western Bituminous region. According to the EIA, coal produced in the Western Region decreased from approximately 335 million short tons in 2022 to around 320 million short tons in 2023. The Powder River Basin is located in northeastern Wyoming and southeastern Montana and is the largest producing region in the United States. Coal from this region is sub-bituminous coal with low sulfur content ranging from 0.2% to 0.9% and heating values ranging from 8,300 to 9,500 BTU/lb. Powder River Basin coal generally has a lower heat content than other regions and is produced from thick seams using surface recovery methods. The Western Bituminous region includes Colorado, Utah and southern Wyoming. Coal from this region typically has low sulfur content ranging from 0.4% to 0.8% and heating values ranging from 10,000 to 12,200 BTU/lb. Western

9

Bituminous coal has certain quality characteristics, especially its higher heat content, low ash and low sulfur, that make this a desirable coal for domestic and international power producers.

Appalachia is divided into north, central and southern regions. According to the EIA, coal produced in the Appalachian region increased from approximately 161 million short tons in 2022 to around 167 million short tons in 2023. Appalachian coal is located near the prolific eastern shale-gas producing regions. Central Appalachian thermal coal is disadvantaged for power generation because of the depletion of economically attractive reserves, increasing costs of production, and permitting issues. However, virtually all U.S. metallurgical coal is produced in Appalachia and the relative scarcity and high quality of this coal allows for a pricing premium over thermal coal. Appalachia, while still a major producer of thermal coal, is undergoing a shift towards heavier reliance on metallurgical coal production for both domestic and international use. This is especially the case in Central Appalachia.

Northern Appalachia includes Pennsylvania, Northern West Virginia, Ohio and Maryland. Coal from this region generally has a high heat value ranging from 10,300 to 13,500 BTU/lb. and a sulfur content ranging from 0.8% to 4.0%. Central Appalachia includes Southern West Virginia, Virginia, Kentucky and Northern Tennessee. Coal mined from this region generally has a high heat value ranging from 11,400 to 13,200 BTU/lb. and low sulfur content ranging from 0.2% to 2.0%. Southern Appalachia primarily covers Alabama and generally has a heat content ranging from 11,300 to 12,300 BTU/lb. and a sulfur content ranging from 0.7% to 3.0%. Southern Appalachia mines are primarily focused on metallurgical markets.

The Interior coal region includes Arkansas, Illinois, Kansas, Louisiana, Mississippi, Missouri, Oklahoma, Texas, and Western Kentucky. The Illinois Basin is the largest producing region in the Interior and consists of Illinois, Indiana and western Kentucky. According to the EIA, coal produced in the Interior Region decreased from approximately 98 million short tons in 2022 to around 95 million short tons in 2023. Coal from the Illinois Basin generally has a heat value ranging from 10,100 to 12,600 BTU/lb. and has a sulfur content ranging from 1.0% to 4.3%. Despite its high sulfur content, coal from the Illinois Basin can generally be used by electric power generation facilities that have installed emissions control devices, such as scrubbers.

Coal Mining Methods

The geological characteristics of our coal reserves largely determine the coal mining method we employ. We use two primary methods of mining coal: underground mining and surface mining.

Underground Mining. We use underground mining methods when coal is located deep beneath the surface. We have included the identity and location of our underground mining operations below under “Our Mining Operations-General.”

Our underground mines are typically operated using one or both of two different mining techniques: longwall mining and room-and-pillar mining.

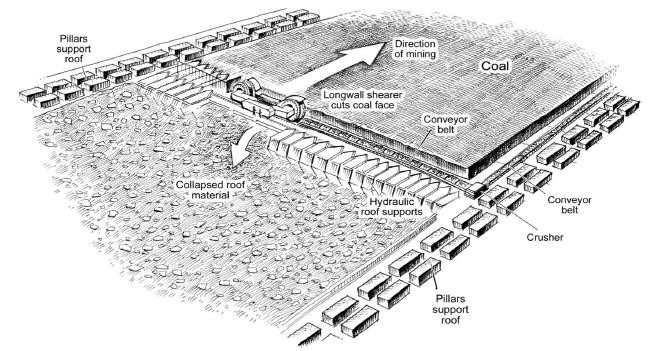

Longwall Mining. Longwall mining involves using a mechanical shearer to extract coal from long rectangular blocks of medium to thick seams. Ultimate seam recovery using longwall mining techniques can exceed 75%. In longwall mining, continuous miners are used to develop access to these long rectangular coal blocks. Hydraulically powered supports temporarily hold up the roof of the mine while a rotating drum mechanically advances across the face of the coal seam, cutting the coal from the face. Chain conveyors then move the loosened coal to an underground mine conveyor system for delivery to the surface. Once coal is extracted from an area, the roof is allowed to collapse in a controlled fashion behind the hydraulic roof supports. Depending on the depth of the cover, the seam thickness and

10

overlying geology, the collapse of the roof can cause surface subsidence. The following diagram illustrates a typical underground mining operation using longwall mining techniques:

Room-and-Pillar Mining. Room-and-pillar mining is effective for small blocks of thin coal seams or larger blocks of thicker coal that has more variable geologic conditions. In room-and-pillar mining, a network of rooms is cut into the coal seam, leaving a series of pillars of coal to support the roof of the mine. Continuous miners are used to cut the coal and shuttle cars are used to transport the coal to a conveyor belt for further transportation to the surface. The pillars generated as part of this mining method can constitute up to 40% of the total coal in a seam. Higher seam recovery rates can be achieved if retreat mining is used. In retreat mining, coal is mined from the pillars as workers retreat. As retreat mining occurs, the roof is allowed to collapse in a controlled fashion.

11

The following diagram illustrates our typical underground mining operation using room-and-pillar mining techniques:

Coal Preparation and Blending. We crush the coal mined from our Powder River Basin mining complexes and ship it directly from our mines to the customer. Typically, no additional preparation is required for a saleable product. Coal extracted from some of our underground mining operations contains impurities, such as rock, shale and clay occupying a wide range of particle sizes. All of our mining operations in the Appalachia region use a coal preparation plant located near the mine or connected to the mine by a conveyor. These coal preparation plants allow us to process the coal we extract from those mines to ensure a consistent quality and to enhance its suitability for particular end-users. In addition, depending on coal quality and customer requirements, we may blend coal mined from different locations, including coal produced by third parties, in order to achieve a more suitable product.

The processes we employ at our preparation plants depend on the size of the raw coal. For coarse material, the separation process relies on the difference in the density between coal and waste rock and, for the very fine fractions, the separation process relies on the difference in surface chemical properties between coal and the waste minerals. To remove impurities, we crush raw coal and classify it into various sizes. For the largest size fractions, we use dense media vessel separation techniques in which we float coal in a tank containing a liquid of a pre-determined specific gravity. Since coal is lighter than its impurities, it floats, and we can separate it from rock and shale. We treat intermediate sized particles with dense medium cyclones, in which a liquid is spun at high speeds to separate coal from rock. Fine coal is treated in spirals, in which the differences in density between coal and rock allow them, when suspended in water, to be separated. Ultra fine coal is recovered in column flotation cells utilizing the differences in surface chemistry between coal and rock. By injecting stable air bubbles through a suspension of ultra-fine coal and rock, the coal particles adhere to the bubbles and rise to the surface of the column where they are removed. To minimize the moisture content in coal, we process most coal sizes through centrifuges. A centrifuge spins coal very quickly, causing water accompanying the coal to separate.

12

For more information about the locations of our preparation plants, you should see the section entitled “Our Mining Operations.”

Surface Mining. We use surface mining when coal is found close to the surface. We have included the identity and location of our surface mining operations below under “Our Mining Operations-General.” The majority of the thermal coal we produce comes from surface mining operations.

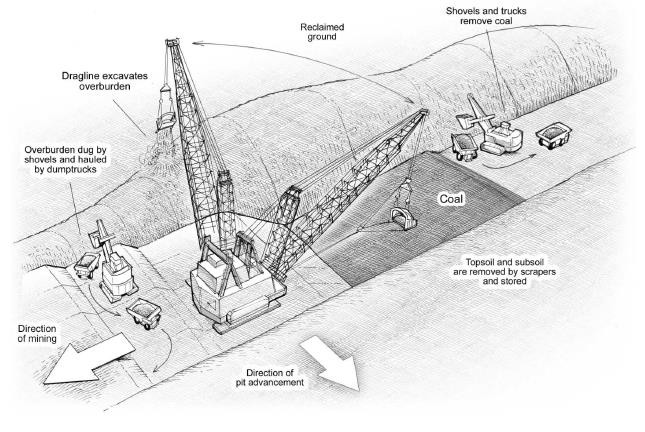

Surface mining involves removing the topsoil then drilling and blasting the overburden (earth and rock covering the coal) with explosives. We then remove the overburden with heavy earth-moving equipment, such as draglines, power shovels, excavators and loaders. Once exposed, we drill, fracture and systematically remove the coal using haul trucks or conveyors to transport the coal to a preparation plant or to a loadout facility. We reclaim disturbed areas as part of our normal mining activities. After final coal removal, we use draglines, power shovels, excavators or loaders to backfill the remaining pits with the overburden removed at the beginning of the process. Once we have replaced the overburden and topsoil, we reestablish native vegetation and plant life into the natural habitat and make other improvements that have local community and environmental benefits.

The following diagram illustrates a typical dragline surface mining operation:

13

Our Mining Operations

General. At December 31, 2023, we operated seven active mines in the United States. The Company reports its results of operations primarily through two reportable segments: the Metallurgical (MET) segment, containing the Company’s metallurgical operations in West Virginia, and the Thermal segment containing the Company’s thermal operations in Wyoming and Colorado. For additional information about the operating results of each of our segments for the years ended December 31, 2023, 2022, and 2021, see Note 23, “Segment Information” to the Consolidated Financial Statements.

In general, we have developed our mining complexes and preparation plants at strategic locations in close proximity to rail or barge shipping facilities. Coal is transported from our mining complexes to customers by means of railroads, trucks, barge lines, and ocean-going vessels from terminal facilities. We currently own or lease under long-term arrangements all of the equipment utilized in our mining operations. We employ sophisticated preventative maintenance and rebuild programs and upgrade our equipment to ensure that it is productive, well-maintained and cost-competitive.

In November of 2021, we sold our equity investment in Knight Hawk Holdings, LLC, which had been part of our Corporate, Other and Eliminations grouping. For further information on the sale of Knight Hawk Holdings, LLC, please see Note 4, “Divestitures” to the Consolidated Financial Statements.

The following map shows the locations of our active, royalty and undeveloped mining operations. Note that this is limited to those properties in which we have current mining operations or expect to have an economic benefit due to mining activity in the future:

14

The following table provides a summary of information regarding our active mining complexes as of December 31, 2023, including the total tons sold associated with these complexes for the years ended December 31, 2023, 2022, and 2021 and the total reserves associated with these complexes at December 31, 2023. The amount disclosed below for the total cost of property, plant and equipment of each mining complex does not include the costs of the coal reserves that we have assigned to an individual complex. The Company owns 100% of the active mining complexes below.

Total Cost | |||||||||||||||||

of Property, | |||||||||||||||||

Plant and | |||||||||||||||||

Equipment | Total | ||||||||||||||||

at | Recoverable | ||||||||||||||||

Mining | Tons Sold (1) | December | Mineral | ||||||||||||||

Mining Complex |

| Mines |

| Equipment |

| Railroad |

| 2021 |

| 2022 |

| 2023 |

| 31, 2023 |

| Reserves | |

(Million | |||||||||||||||||

($ millions) |

| tons) | |||||||||||||||

Metallurgical: |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

Leer |

| U |

| LW, CM |

| CSX |

| 4.6 |

| 3.9 |

| 4.3 | $ | 363.2 |

| 36.1 | |

Leer South |

| U |

| LW, CM |

| CSX |

| 0.8 |

| 2.2 |

| 2.7 |

| 713.9 |

| 62.7 | |

Beckley |

| U |

| CM |

| CSX |

| 1.1 |

| 0.9 |

| 1.2 |

| 118.6 |

| 25.3 | |

Mountain Laurel |

| U |

| CM |

| CSX |

| 1.0 |

| 0.8 |

| 1.1 |

| 92.6 |

| 16.6 | |

Thermal: |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| ||||||||||

Black Thunder |

| S |

| D, S |

| UP/BN |

| 60.2 |

| 62.3 |

| 60.5 | 260.2 |

| 420.0 | ||

Coal Creek |

| S |

| D, S |

| UP/BN |

| 2.0 |

| 3.8 |

| 2.3 |

| 0.3 |

| — | |

West Elk |

| U |

| LW, CM |

| UP |

| 3.0 |

| 4.3 |

| 2.9 |

| 31.2 |

| 38.2 | |

Totals |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 72.7 |

| 78.2 |

| 75.0 | $ | 1,580.0 |

| 598.9 | |

| (1) | Tons of coal we purchased from third parties that were not processed through our loadout facilities are not included in the amounts shown in the table above. |

In October 2018, the Securities and Exchange Commission (“SEC”) adopted amendments to its current disclosure rules to modernize the mineral property disclosure requirements for mining registrants. The amendments include the adoption of S-K 1300, which will govern disclosure for mining registrants (the “SEC Mining Modernization Rules”).

Descriptions in this report of our mineral reserves and resources are prepared in accordance with S-K 1300, as well as similar information provided by other issuers in accordance with S-K 1300, may not be comparable to similar information that is presented elsewhere outside of this report. Please refer to the Technical Report Summaries (“TRS”) filed as Exhibits 96.1-96.3 to our Annual Report on Form 10-K for the period ended December 31, 2023 for additional information with respect to our material properties. Refer to Item 2. Properties for further discussion on the reserves and material properties.

Metallurgical

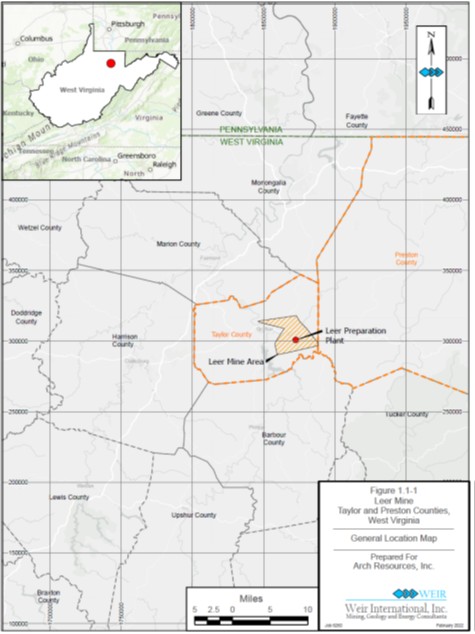

Leer. The Leer Complex is a longwall operation, located in Taylor County, West Virginia, that includes approximately 36.1 million tons of proven and probable coal reserves as of December 31, 2023 and is primarily sold as High-Vol A metallurgical quality coal in the Lower Kittanning seam, and is part of approximately 93,300 acres that is considered our Tygart Valley area. A significant portion of the reserves at Leer are owned rather than leased from third parties.

15

All the production is processed through a 1,400 ton-per-hour preparation plant and loaded on the CSX railroad. A 15,000-ton train can be loaded in less than four hours.

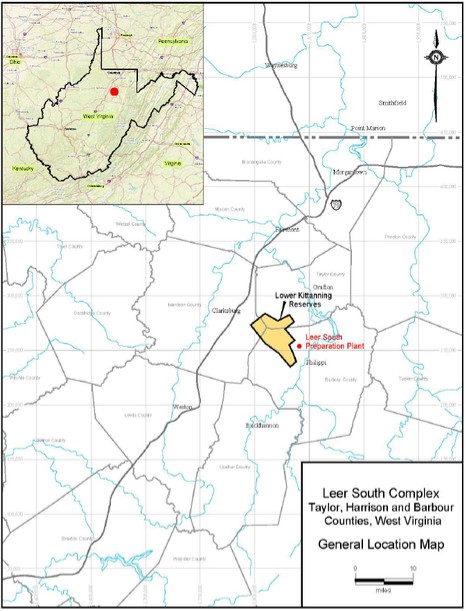

Leer South. The Leer South mining complex is a longwall operation in the Lower Kittanning seam with a preparation plant and a loadout facility located on approximately 26,600 acres in Barbour County, West Virginia. The 1,600 ton-per-hour preparation plant is located near the mine, and the loadout facility is served by the CSX railroad and connected to the plant by a 4,000 ton-per-hour conveyor system. The loadout facility is capable of loading a 15,000 ton unit train in less than four hours.

Coal quality is primarily High-Vol A metallurgical coal similar to our Leer Complex. The Leer South mining complex had approximately 62.7 million tons of proven and probable reserves at December 31, 2023. A significant portion of the reserves at Leer South are owned rather than leased from third parties.

Beckley. The Beckley mining complex is located on approximately 16,700 acres in Raleigh County, West Virginia. Beckley is extracting high quality, Low-Vol metallurgical coal in the Pocahontas No. 3 seam. The Beckley mining complex had approximately 25.3 million tons of proven and probable reserves at December 31, 2023.

Coal is conveyed from the mine to a 600-ton-per-hour preparation plant before shipping the coal via the CSX railroad. The loadout facility can load a 10,000-ton train in less than four hours.

Mountain Laurel. Mountain Laurel is an underground mining complex located on approximately 38,200 acres in Logan County and Boone County, West Virginia. Underground mining operations at the Mountain Laurel mining complex extracts High-Vol B metallurgical coal from the Alma and No. 2 Gas seams. The Mountain Laurel mining complex has approximately 16.6 million tons of proven and probable reserves at December 31, 2023.

We process all of the coal through a 1,400-ton-per-hour preparation plant before shipping the coal to our customers via the CSX railroad. The loadout facility can load a 15,000-ton train in less than four hours.

Thermal

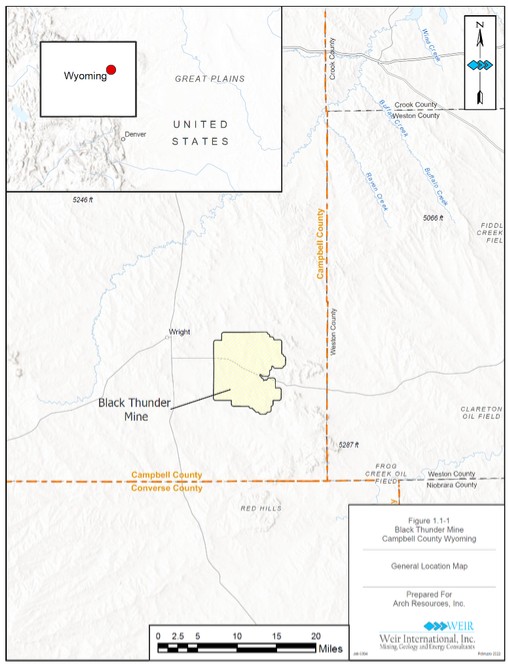

Black Thunder. Black Thunder is a surface mining complex located on approximately 35,300 acres in Campbell County, Wyoming. The Black Thunder complex extracts thermal coal from the Upper Wyodak and Main Wyodak seams.

We control a significant portion of the coal reserves through federal and state leases. The Black Thunder mining complex had approximately 420.0 million tons of proven and probable reserves at December 31, 2023.

The Black Thunder mining complex currently consists of four active pit areas and two active loadout facilities. We ship all of the coal raw to our customers via the Burlington Northern Santa Fe and Union Pacific railroads. We do not process the coal mined at this complex. Each of the loadout facilities can load a 15,000-ton train in less than two hours.

Coal Creek. Coal Creek is a surface mining complex located on approximately 7,400 acres in Campbell County, Wyoming. The Coal Creek mining complex extracts thermal coal from the Wyodak-R1 and Wyodak-R3 seams.

The Coal Creek complex currently consists of one active pit area and a loadout facility. We ship all of the coal raw to our customers via the Burlington Northern Santa Fe and Union Pacific railroads. We do not process the coal mined at this complex. The loadout facility can load a 15,000-ton train in less than three hours.

In alignment with our desire to shrink our operational footprint and associated liabilities, we have committed to systematically reclaiming our Coal Creek operation as sales from the complex taper down.

16

West Elk. West Elk is an underground mining complex located on approximately 18,400 acres in Gunnison County, Colorado. The West Elk mining complex extracts thermal coal from the E seam. We are currently working on developing longwall panels in the B seam at the complex.

We control a significant portion of the coal reserves through federal and state leases. The West Elk mining complex had approximately 38.2 million tons of proven and probable reserves at December 31, 2023.

The West Elk complex currently consists of a longwall, continuous miner sections, a preparation plant, and a loadout facility. We ship most of the coal raw to our customers via the Union Pacific railroad. When required to improve the quality of some of our coal production, it is processed through the 800 ton-per-hour preparation plant. The loadout facility can load an 11,000-ton train in less than three hours.

Sales, Marketing and Trading

Overview. Coal prices are influenced by a number of factors and can vary materially by region. The price of coal within a region is influenced by general marketplace conditions, the supply and price of alternative fuels to coal (such as natural gas and subsidized renewables), production costs, coal quality, transportation costs involved in moving coal from the mine to the point of use and mine operating costs. For example, in thermal coal markets, higher heat and lower ash content generally result in higher prices, and higher sulfur and higher ash content generally result in lower prices within a given geographic region. In metallurgical coal markets, chemical properties within the coal and transportation costs determine price differences.

The cost of producing coal at the mine is also influenced by geologic characteristics such as seam thickness, overburden ratios and depth of underground reserves. It is generally less expensive to mine coal seams that are thick and located close to the surface than to mine thin underground seams. Within a particular geographic region, underground mining, which is the mining method we use in our Appalachian mines, is generally more expensive than surface mining, which is the mining method we use in the Powder River Basin. This is the case because of the higher capital costs relative to the reserve base, including costs for construction of extensive ventilation systems, and higher per unit labor costs due to lower productivity associated with underground mining.

Our sales, marketing and trading functions are principally based in St. Louis, Missouri and consist of sales and trading, transportation and distribution, quality control and contract administration personnel as well as revenue management. We also have sales employees in our Singapore and London offices. In addition to selling coal produced from our mining complexes, from time to time we purchase and sell coal mined by others, some of which we blend with coal produced from our mines. We focus on meeting the needs and specifications of our customers rather than just selling our coal production.

Customers. The Company markets its metallurgical and thermal coal to domestic and foreign steel producers, domestic and foreign power generators, and other industrial facilities. For the year ended December 31, 2023, we derived approximately 15% of our total coal revenues from sales to our three largest customers, JFE Steel Corporation, T S Global Procurement Company Pte. and Southern Company and approximately 39% of our total coal revenues from sales to our 10 largest customers.

In 2023, we sold coal to domestic customers located in 29 different states. The locations of our mines enable us to ship coal to most of the major coal-fueled power plants in the United States.

In addition, in 2023, we exported coal to Europe, Asia, Central and South America, and Africa. Revenue from exports to seaborne countries was $1.8 billion, $2.3 billion and $1.1 billion for the years ended December 31, 2023, 2022 and 2021, respectively. As of December 31, 2023 and 2022, trade receivables related to metallurgical-quality coal sales totaled $206.3 million and $142.9 million, respectively, or 75% and 60% of total trade receivables, respectively. We do not have foreign currency exposure for our international sales as all sales are denominated and settled in U.S. dollars.

17

The Company’s seaborne revenues by coal shipment destination for the year ended December 31, 2023, were as follows:

(In thousands) |

|

| |

Europe | $ | 696,975 | |

Asia |

| 935,158 | |

Central and South America |

| 136,423 | |

Africa | 4,971 | ||

Total | $ | 1,773,527 |

Long-Term Coal Supply Arrangements

As is customary in the coal industry, we enter into fixed price, fixed volume term-based supply contracts, the terms of which are sometimes more than one year (“long-term”), with many of our customers. Multiple year contracts usually have specific and possibly different volume and pricing arrangements for each year of the contract. Long-term contracts allow customers to secure a supply for their future needs and provide us with greater predictability of sales volume and sales prices. In 2023, we sold approximately 75% of the tonnage (representing approximately 46% of the Company’s revenues) of our coal under long-term supply arrangements. The majority of our supply contracts include a fixed price for the term of the agreement or a pre-determined escalation in price for each year. Some of our long-term supply agreements may include a variable pricing system. While most of our sales contracts are for terms of one to five years, some are as short as one month. At December 31, 2023, the average volume-weighted remaining term of our long-term contracts for metallurgical and thermal coal was approximately 2.5 years, with remaining terms ranging from one to four years. At December 31, 2023, remaining tons under long-term supply agreements, including those subject to price re-opener or extension provisions, were approximately 110.2 million tons.

We typically sell coal to North American customers under term arrangements through a “request-for-proposal” process. We also respond to private solicitations and generally do not know if a customer intends to buy the coal for which they solicited. The terms of our coal sales agreements are dictated by the availability and price of alternative fuels, general marketplace conditions, the quality of the coal we have available to sell, our mine operations (including operating costs), the length of contract, as well as negotiations with customers. Consequently, the terms of these contracts may vary to some extent by customer, including base price adjustment features, price re-opener terms, coal quality requirements, quantity parameters, permitted sources of supply, future regulatory changes, extension options, force majeure, termination, damages and assignment provisions. Our long-term supply contracts typically contain provisions to adjust the base price due to new governmental statutes, ordinances or regulations. We typically sell our metallurgical coal to non-North American customers based on various indices or agreements to mutually negotiate the price. These agreements generally are for one year and can reset pricing with each shipment. Additionally, some of our contracts contain provisions that allow for the recovery of costs affected by modifications or changes in the interpretations or application of any applicable statute by local, state or federal government authorities. These provisions only apply to the base price of coal contained in these supply contracts. In some circumstances, a significant adjustment in base price can lead to termination of the contract.

Certain of our contracts contain index provisions that change the price based on changes in market based indices or changes in economic indices or both. Certain of our contracts contain price re-opener provisions that may allow a party to commence a renegotiation of the contract price at a pre-determined time. Price re-opener provisions may automatically set a new price based on prevailing market price or, in some instances, require us to negotiate a new price, sometimes within a specified range of prices. In a limited number of agreements, if the parties do not agree on a new price, either party has an option to suspend the agreement for the pricing period not agreed to. In addition, certain of our contracts contain clauses that may allow customers to terminate the contract in the event of certain changes in environmental laws and regulations that impact their operations.

Customers are generally required to take their coal on a ratable basis but have been known to push sales out in low demand periods when contract prices are higher. Each of these situations must be dealt with on an individual basis.

18

Coal quality and volumes are stipulated in coal sales agreements. In most cases, the annual pricing and volume obligations are fixed, although in some cases the volume specified may vary depending on the customer consumption requirements. Most of our coal sales agreements contain provisions requiring us to deliver coal within certain ranges for specific coal characteristics such as heat content (for thermal coal contracts), volatile matter (for metallurgical coal contracts), and for both types of contracts, sulfur, ash and moisture content. Failure to meet these specifications can result in economic penalties, suspension or cancellation of shipments or termination of the contracts.

Our coal sales agreements also typically contain force majeure provisions allowing temporary suspension of performance by us or our customers, during the duration of events beyond the control of the affected party, including events such as strikes, adverse mining conditions, mine closures or serious transportation problems that affect us or unanticipated plant outages that may affect the buyer. Our contracts also generally provide that in the event a force majeure circumstance exceeds a certain time period, the unaffected party may have the option to terminate the purchase or sale in whole or in part. Some contracts stipulate that this tonnage can be made up by mutual agreement or at the discretion of the buyer. Agreements between our customers and the railroads servicing our mines may also contain force majeure provisions.

In most of our thermal coal contracts, we have a right of substitution (unilateral or subject to counterparty approval), allowing us to provide coal from different mines, including third-party mines, as long as the replacement coal meets quality specifications and will be sold at the same equivalent delivered cost.

In some of our coal supply contracts, we agree to indemnify or reimburse our customers for damage to their or their rail carrier’s equipment while on our property, which results from our or our agents’ negligence, and for damage to our customer’s equipment due to non-coal materials being included with our coal while on our property.

Trading. In addition to marketing and selling coal to customers through traditional coal supply arrangements, we seek to optimize our coal production and leverage our knowledge of the coal industry through a variety of other marketing, trading and asset optimization strategies. From time to time, we may employ strategies to use coal and coal-related commodities and contracts for those commodities in order to manage and hedge volumes and/or prices associated with our coal sales or purchase commitments, reduce our exposure to the volatility of market prices or augment the value of our portfolio of traditional assets. These strategies may include physical coal contracts, as well as a variety of forward, futures or options contracts, swap agreements or other financial instruments, in coal or other commodities such as natural gas and foreign currencies.

We maintain a system of complementary processes and controls designed to monitor and manage our exposure to market and other risks that may arise as a consequence of these strategies. These processes and controls seek to preserve our ability to profit from certain marketing, trading and asset optimization strategies while mitigating our exposure to potential losses.

Transportation. We generally sell coal to international customers at export terminals, and we are usually responsible for the cost of transporting coal to the export terminals. We transport our coal to Atlantic coast terminals, Pacific cost terminals or terminals along the Gulf of Mexico for transportation to international customers. Our international customers are generally responsible for paying the cost of ocean freight. We may also sell coal to international customers delivered to an unloading facility at the destination country.

We own a 35% interest in Dominion Terminal Associates LLP (DTA), a limited liability partnership that operates a ground storage-to-vessel coal transloading facility in Newport News, Virginia. The facility has a rated throughput capacity of 20 million tons of coal per year and ground storage capacity of approximately 1.7 million tons. The facility primarily serves international customers, as well as domestic coal users located along the Atlantic coast of the United States. From time-to-time, we may lease a portion of our port capacity to third parties. DTA is in need of capital investment to maximize functionality and minimize downtime to mechanical issues. Together with DTA leadership and ownership partners, we are evaluating a needs assessment and rough timeline for the recommended work. In connection with expected capital investments at DTA, we expect the total investment to be between $57 million and $85 million which equates to our 35% share between $20.0 million and $30.0 million on contributions for equity affiliate in 2024.

19

Additionally, we have entered into throughput agreements with third parties to facilitate international shipments. The majority of our international metallurgical shipments are shipped through DTA or Curtis Bay, which is strategically located on the CSX network and the Chesapeake Bay.

We ship our coal to domestic customers by means of railcars, barges, or trucks, or a combination of these means of transportation. We generally sell coal used for domestic consumption free on board (f.o.b.) at the mine or nearest loading facility. Our domestic customers normally bear the costs of transporting coal by rail, barge or truck.

Historically, most domestic electricity generators have arranged long-term shipping contracts with rail, trucking or barge companies to assure stable delivery costs. Transportation can be a large component of a purchaser’s total cost. Although the purchaser pays the freight, transportation costs still are important to coal mining companies because the purchaser may choose a supplier largely based on cost of transportation. Transportation costs borne by the customer vary greatly based on each customer’s proximity to the mine, our proximity to the loadout facilities and the provisions of their specific transportation agreements. Trucks and overland conveyors haul coal over shorter distances, while barges, Great Lake carriers and ocean vessels move coal to export markets and domestic markets requiring shipment over the Great Lakes and several river systems.

Most coal mines are served by a single rail company, but much of the Powder River Basin, including our mines, are served by two rail carriers: the Burlington Northern-Santa Fe railroad and the Union Pacific railroad. We generally transport coal produced at our Appalachian mining complexes via the CSX railroad. Besides rail deliveries, some customers in the eastern United States rely on a river barge system or over-the-road trucks.

Competition

The coal industry is intensely competitive with alternative energy sources outside of the industry and between producing companies. The most important factors on which we compete are coal quality, delivered costs to the customer and reliability of supply. Our principal domestic coal-producing peers include Allegheny Metallurgical; Alpha Metallurgical Resources Inc.; Blackhawk Mining LLC; Coronado Coal LLC; Corsa Coal Corp.; Eagle Specialty Materials LLC; Navajo Transitional Energy Company LLC; Peabody Energy Corp.; Ramaco Resources; and Warrior Met Coal, Inc. Some of these coal producers are larger than we are and may have greater financial resources and larger reserve bases than we do. We also compete directly with a number of smaller producers in each of the geographic regions in which we operate, as well as companies that produce coal from one or more foreign countries, such as Australia, Canada, Colombia, Indonesia, South Africa and Russia.

Our principal competitor in thermal coal is natural gas, other alternative fuels, and subsidized renewables. Specifically, coal competes directly with other fuels, such as natural gas, nuclear energy, hydropower, subsidized renewable, and petroleum, for steam and electrical power generation. Costs and other factors relating to these alternative fuels, such as safety and environmental considerations, as well as tax incentives and various mandates, affect the overall demand for coal as a fuel and the price we can charge for the coal. Rail rates and the performance of the railroads, which are generally controlled by our customers, meaningfully impacts our competitiveness with other producers and alternative fuel sources. For example, rail rates for domestic coal, a cost that we cannot control, can account for over two-thirds of the delivered cost of the product.

Suppliers

Principal supplies used in our business include petroleum-based fuels, explosives, tires, steel and other raw materials as well as spare parts and other consumables used in the mining process. We use third-party suppliers for a significant portion of our equipment rebuilds and repairs, drilling services and construction. We use sole source suppliers for certain parts of our business such as explosives and fuel, and preferred suppliers for other parts of our business such as original equipment suppliers, dragline and shovel parts and related services. We believe adequate substitute suppliers are available. For more information about our suppliers, you should see Item 1A, “Risk Factors-Inflationary pressures on mining and other industrial supplies, including steel-based supplies, diesel fuel and rubber tires, or the inability to obtain a sufficient quantity of those supplies, could negatively affect our operating costs or disrupt or delay our production.”

20

Environmental and Other Regulatory Matters

Coal mining is one of the most regulated and inspected industrial activities in the United States. Federal, state and local authorities regulate the U.S. coal mining industry with respect to matters such as employee health and safety and the environment, including the protection of air quality, water quality, wetlands, special status species of plants and animals, land uses, cultural and historic properties and other environmental resources identified during the permitting process. Reclamation is required during production and after mining has been completed. Materials used and generated by mining operations must also be managed according to applicable regulations and law. These laws have, and will continue to have, a significant effect on our production costs and our competitive position.

We endeavor to conduct our mining operations in compliance with applicable federal, state and local laws and regulations. However, due in part to the extensive, comprehensive and changing regulatory requirements, violations during mining operations occur from time to time. We cannot assure you that we have been or will be at all times in complete compliance with such laws and regulations. Expenditures we incur to maintain compliance with all applicable federal and state laws have been and are expected to continue to be significant and increase overtime. Federal and state mining laws and regulations require us to obtain surety bonds to guarantee performance or payment of certain long-term obligations, including mine closure and reclamation costs, federal and state workers’ compensation benefits, coal leases and other miscellaneous obligations. Compliance with these laws has substantially increased the cost of coal mining for domestic coal producers.

Future laws, regulations or orders, as well as future interpretations, changes in political policies and more rigorous enforcement of existing laws, regulations or orders, may require substantial increases in equipment and operating costs and delays, interruptions or a termination of operations, the extent to which we cannot predict. Future laws, regulations or orders may also cause coal to become a less attractive fuel source, thereby reducing coal’s share of the market for fuels and other energy sources used to generate electricity. As a result, future laws, regulations or orders may adversely affect our mining operations, cost structure or our customers’ demand for coal.

The following is a summary of the various federal and state environmental and similar regulations that have a material impact on our business:

Mining Permits and Approvals. Numerous governmental permits or approvals are required for mining operations. When we apply for these permits and approvals, we may be required to prepare and present to federal, state or local authorities’ data pertaining to the effect or impact that any proposed production or processing of coal may have on the environment. For example, in order to obtain a federal coal lease, the U.S. Department of the Interior, Bureau of Land Management (“BLM”) must prepare an environmental impact statement to assist the BLM in determining the potential environmental impact of lease issuance, including any collateral effects from the mining, transportation and burning of coal, which may in some cases include a review of impacts on climate change. The authorization, permitting and implementation requirements imposed by federal, state and local authorities may be costly and time consuming and may delay commencement or continuation of mining operations. In the states where we operate, the applicable laws and regulations also provide that a mining permit or modification can be delayed, refused or revoked if officers, directors, shareholders with specified interests or certain other affiliated entities with specified interests in the applicant or permittee have, or are affiliated with another entity that has, outstanding permit violations. Thus, past or ongoing violations of applicable laws and regulations could provide a basis to revoke existing permits and to deny the issuance of additional permits.

In order to obtain mining permits and approvals from federal and state regulatory authorities, mine operators must submit a reclamation plan for restoring, upon the completion of mining operations, the mined property to its prior condition or other authorized use. Typically, we submit the necessary permit applications several months or even years before we plan to begin mining a new area. Some of our required permits are becoming increasingly more difficult and expensive to obtain, and the application review processes are taking longer to complete and becoming increasingly subject to challenge and political manipulation even after a permit has been issued.

21

Under some circumstances, substantial fines and penalties, including revocation or suspension of mining permits, may be imposed under the laws described above. Monetary sanctions and, in severe circumstances, criminal sanctions may be imposed for failure to comply with these laws.

Surface Mining Control and Reclamation Act. The Surface Mining Control and Reclamation Act, which we refer to as SMCRA, establishes mining, environmental protection, reclamation and closure standards for all aspects of surface mining as well as many aspects of underground mining. Mining operators must obtain SMCRA permits and permit renewals from the Office of Surface Mining, which we refer to as OSM, or from the applicable state agency if the state agency has obtained regulatory primacy. A state agency may achieve primacy if the state regulatory agency develops a mining regulatory program that is no less stringent than the federal mining regulatory program under SMCRA. All states in which we conduct mining operations have achieved primacy and issue permits in lieu of OSM, but are still subject to federal oversight.

SMCRA permit provisions include a complex set of requirements which include, among other things, coal prospecting; mine plan development; topsoil or growth medium removal and replacement; selective handling of overburden materials; mine pit backfilling and grading; disposal of excess spoil; protection of the hydrologic balance; subsidence control for underground mines; surface runoff and drainage control; establishment of suitable post mining land uses; and revegetation. We begin the process of preparing a mining permit application by collecting baseline data to adequately characterize the pre-mining environmental conditions of the permit area. This work is typically conducted by third-party consultants with specialized expertise and includes surveys and/or assessments of the following: cultural and historical resources; geology; soils; vegetation; aquatic organisms; wildlife; potential for threatened, endangered or other special status species; surface and ground water hydrology; climatology; riverine and riparian habitat; and wetlands. The geologic data and information derived from the other surveys and/or assessments are used to develop the mining and reclamation plans presented in the permit application. The mining and reclamation plans address the provisions and performance standards of the state’s equivalent SMCRA regulatory program, and are also used to support applications for other authorizations and/or permits required to conduct coal mining activities. Also included in the permit application is information used for documenting surface and mineral ownership, variance requests, access roads, bonding information, mining methods, mining phases, other agreements that may relate to coal, other minerals, oil and gas rights, water rights, permitted areas, and ownership and control information required to determine compliance with OSM’s Applicant Violator System, including the mining and compliance history of officers, directors and principal owners of the entity.

Once a permit application is prepared and submitted to the regulatory agency, it goes through an administrative completeness review and a thorough technical review. Also, before a SMCRA permit is issued, a mine operator must submit a bond or otherwise secure the performance of all reclamation obligations. After the application is submitted, a public notice or advertisement of the proposed permit is required to be given, which begins a notice period that is followed by a public comment period before a permit can be issued. It is not uncommon for a SMCRA mine permit application to take over a year to prepare, depending on the size and complexity of the mine, and anywhere from six months to two years or even longer for the permit to be issued. The variability in time frame required to prepare the application and issue the permit can be attributed primarily to the various regulatory authorities’ discretion in the handling of comments and objections relating to the project received from the general public and other agencies. Also, it is not uncommon for a permit to be delayed as a result of litigation related to the specific permit or another related company’s permit.

In addition to the bond requirement for an active or proposed permit, the Abandoned Mine Land Fund, which was created by SMCRA, requires that a fee be paid on all coal produced. The proceeds of the fee are used to restore mines closed or abandoned prior to SMCRA’s adoption in 1977, as well as fund other state and federal initiatives. For the first three quarters of 2023, the fee was $0.28 per ton of coal produced from surface mines and $0.12 per ton of coal produced from underground mines. As a result of the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act of 2021, which included the Abandoned Mine Land Reclamation Amendments of 2021, the fees decreased as of the calendar quarter beginning October 1, 2021. The current fee is $0.224 per ton of coal produced from surface mines and $0.096 per ton of coal produced from underground mines. In 2023, we recorded $15.1 million of expense related to these reclamation fees.

22

Surety Bonds. Mine operators are often required by federal and/or state laws, including SMCRA, to assure, usually through the use of surety bonds, payment of certain long-term obligations including mine closure or reclamation costs, federal and state workers’ compensation costs, coal leases and other miscellaneous obligations. Although surety bonds are usually non-cancelable during their term, many of these bonds are renewable on an annual basis and collateral requirements may change.

The costs of these bonds have widely fluctuated in recent years while the market terms of surety bonds have remained difficult for mine operators. These changes in the terms of the bonds have been accompanied at times by a decrease in the number of companies willing to issue surety bonds. As of December 31, 2023, we posted an aggregate of approximately $456.3 million in surety bonds, cash, and letters of credit outstanding for reclamation purposes.

At December 31, 2023, the Company maintains a fund for asset retirement obligations at our Black Thunder mine and thus far has contributed $142.3 million that will serve to defease the long-term asset retirement obligation for its thermal asset base.

For additional information, please see “Failure to obtain or renew surety bonds on acceptable terms could affect our ability to secure reclamation and coal lease obligations and, therefore, our ability to mine or lease coal, which could have a material adverse effect on our business and results of operations,” contained in Item 1A, “Risk Factors—Risk Related to Our Operations,” for a discussion of certain risks associated with our surety bonds.