cresudfs

United

States

SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION

Washington, D.C. 20549

FORM 20-F

|

☐

|

|

REGISTRATION STATEMENT PURSUANT TO SECTION 12(b) OR (g) OF THE

SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934

|

OR

|

☒

|

|

ANNUAL REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES

EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934

|

For the fiscal year ended: June 30, 2020

OR

|

☐

|

|

TRANSITION REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES

EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934

|

OR

|

☐

|

|

SHELL COMPANY REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE

SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934

Date of event requiring this shell company report ___

For the transition period from ___ to___

|

Commission file number: 001-29190

Cresud SOCIEDAD ANONIMA COMERCIAL INMOBILIARIA FINANCIERA Y

AGROPECUARIA

(Exact name of Registrant as specified in its charter)

Cresud Inc.

(Translation of Registrant’s name into English)

Republic of Argentina

(Jurisdiction of incorporation or organization)

Moreno 877, 23rd Floor,

(C1091AAQ) City of Buenos Aires, Argentina

(Address of principal executive offices)

Matías Iván Gaivironsky

Chief Financial and Administrative Officer

Tel +(5411) 4323-7449 – ir@cresud.com.ar

Moreno 877, 24th Floor,

(C1091AAQ) City of Buenos Aires, Argentina

(Name, Telephone, E-mail and/or Facsimile number and Address of

Company Contact Person)

Securities registered or to be registered pursuant to Section 12(b)

of the Act:

|

Title of each class

|

|

|

TradingSymbols

|

|

|

Name of each exchange on which registered

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

American Depositary Shares (ADSs), each representing

ten shares of Common Stock

|

|

|

CRESY

|

|

|

Nasdaq National Market of the

Nasdaq Stock Market

|

|

Common Stock, par value ARS 1.00 per share

|

|

|

CRESY

|

|

|

Nasdaq National Market of the

Nasdaq Stock Market*

|

|

*

|

Not for

trading, but only in connection with the registration of American

Depositary Shares, pursuant to the requirements of the Securities

and Exchange Commission.

|

Securities registered or to be registered pursuant to Section 12(g)

of the Act: None

Securities for which there is a reporting obligation pursuant to

Section 15(d) of the Act: None

Indicate

the number of outstanding shares of each of the issuer’s

classes of capital or common stock as of the period covered by the

annual report: 501,642,804.

Indicate

by check mark if the registrant is a well known seasoned issuer, as

defined in Rule 405 of the Securities Act:

☐ Yes ☒ No

If this

report is an annual or transition report, indicate by check mark if

the registrant is not required to file reports pursuant to Section

13 or 15 (d) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934.

☒ Yes ☐ No

Note:

Checking the box above will not relieve any registrant required to

file reports pursuant to Section 13 or 15(a) of the Securities

Exchange Act of 1934 from their obligations under those

Sections

Indicate

by check mark whether the registrant (1) has filed all reports

required to be filed by Section 13 or 15(d) of the Securities

Exchange Act of 1934 during the preceding 12 months (or for such

shorter period that the registrant was required to file such

reports), and (2) has been subject to such filing requirements for

the past 90 days.

☒ Yes ☐ No

Indicate

by check mark whether the registrant has submitted electronically

every Interactive Data File required to be submitted and posted

pursuant to Rule 405 of Regulation S-T (§232.405 of this

chapter) during the preceding 12 months (or for such shorter period

that the registrant was required to submit such

files).

☒ Yes ☐ No

Indicate

by check mark whether the registrant is a large accelerated filer,

an accelerated filer, a non-accelerated filer or an emerging growth

company. See definition of “large accelerated filer,”

“accelerated filer” and “emerging growth

company” in Rule 12b-2 of the Exchange Act.:

Large

accelerated filer ☐ Accelerated filer

☒ Non-accelerated filer ☐ Emerging growth company ☐

If

an emerging growth company that prepares its financial statements

in accordance with U.S. GAAP, indicate by check mark if the

registrant has elected not to use the extended transition period

for complying with any new or revised financial accounting

standards† provided pursuant to Section 13(a) of the Exchange

Act. ☐

†The

term “new or revised financial accounting standard”

refers to any update issued by the Financial Accounting Standards

Board to its Accounting Standards Codification after April 5,

2012

Indicate

by check mark which basis of accounting the registrant has used to

prepare the financial statements included in this

filing:

|

U.S.

GAAP

|

☐

|

International

Financial Reporting Standards as issued by the International

Accounting Standards Board

|

☒

|

Other

☐

|

If

“Other” has been checked in response to the previous

question, indicate by check mark which financial statement item the

registrant has elected to follow.

☐ Item 17 ☐ Item

18

If this

is an annual report, indicate by check mark whether the registrant

is a shell company (as defined in Rule 12b-2 of the Exchange

Act).

☐ Yes ☒ No

(APPLICABLE ONLY TO

ISSUERS INVOLVED IN BANKRUPTCY PROCEEDINGS DURING THE PAST FIVE

YEARS)

Indicate by check

mark whether the registrant has filed all documents and reports

required to be filed by Sections 12, 23 or 15(d) of the Securities

Exchange Act of 1934 subsequent to the distribution of securities

under a plan confirmed by the court. Yes ☐ No ☐

Please send copies of notices and communications from the

Securities and Exchange Commission to:

|

Carolina

Zang

|

|

David

L.Williams

|

|

|

|

Jaime

Mercado

|

|

Zang

Bergel & Viñes Abogados

|

|

Simpson

Thacher & Bartlett LLP

|

|

Florida

537 piso 18º

C1005AAK Ciudad

Autónoma de Buenos Aires, Argentina.

|

|

425

Lexington Avenue

New

York, NY 10019

|

TABLE OF CONTENTS

|

|

Page No.

|

|

Summary of Risk Factors

|

i

|

|

Disclaimer Regarding Forward-Looking Information

|

iii

|

|

Available information

|

iii

|

|

Presentation of Financial and Certain Other

Information

|

v

|

|

Market Data

|

x

|

|

Part I

|

1

|

|

Item 1. Identity of Directors, Senior Management and

Advisers

|

1

|

|

Item 2. Offer Statistics and Expected Timetable

|

1

|

|

Item 3. Key Information

|

1

|

|

A. Selected Consolidated Financial Data

|

1

|

|

A.1. Local exchange market and exchange rates

|

5

|

|

B. Capitalization and Indebtedness

|

6

|

|

C. Reasons for the Offer and Use of Proceeds

|

6

|

|

D. Risk Factors

|

6

|

|

Item 4. Information on the Company

|

66

|

|

A. History and Development of the Company

|

66

|

|

B. Business Overview

|

92

|

|

C. Organizational Structure

|

169

|

|

D. Property, Plants and Equipment

|

169

|

|

Item 4A. Unresolved Staff Comments

|

172

|

|

Item 5. Operating and Financial Review and Prospects

|

172

|

|

A. Consolidated Operating Results

|

172

|

|

B. Liquidity and Capital Resources

|

240

|

|

C. Research and Developments, Patents and Licenses

|

248

|

|

D. Trend Information

|

249

|

|

E. Off-Balance Sheet Arrangements

|

253

|

|

F. Tabular Disclosure of Contractual Obligations

|

253

|

|

G. Safe Harbor

|

253

|

|

Item 6. Directors, Senior Management and Employees

|

253

|

|

A. Directors and Senior Management

|

253

|

|

B. Compensation

|

258

|

|

C. Board Practices

|

260

|

|

D. Employees

|

261

|

|

E. Share Ownership

|

262

|

|

Item 7. Major shareholders and related party

transactions

|

264

|

|

A. Major Shareholders

|

264

|

|

B. Related Party Transactions

|

265

|

|

C. Interests of Experts and Counsel

|

269

|

|

Item 8. Financial Information

|

269

|

|

A. Audited Consolidated Statements and Other Financial

Information

|

269

|

|

B. Significant Changes

|

280

|

|

Item 9. The Offer and Listing

|

280

|

|

A. Offer and Listing Details

|

280

|

|

B. Plan of Distribution

|

281

|

|

C. Markets

|

281

|

|

D. Selling Shareholders

|

283

|

|

E. Dilution

|

283

|

|

F. Expenses of the Issue

|

283

|

|

Item 10. Additional Information

|

283

|

|

A. Share Capital

|

283

|

|

B. Memorandum and Articles of Association

|

283

|

|

C. Material Contracts

|

291

|

|

D. EXCHANGE CONTROLS

|

291

|

|

E. Money Laundering

|

293

|

|

F. Taxation

|

295

|

|

G. Dividends and Paying Agents

|

302

|

|

H. Statement by Experts

|

302

|

|

I. Documents on Display

|

303

|

|

J. Subsidiary Information

|

303

|

|

Item 11. Quantitative and Qualitative Disclosures about Market

Risk

|

303

|

|

Item 12. Description of Securities Other than Equity

Securities

|

303

|

|

Part II

|

305

|

|

Item 13. Defaults, Dividend Arrearages and

Delinquencies

|

305

|

|

Item 14. Material Modifications to the Rights of Security Holders

and Use of Proceeds

|

305

|

|

Item 15. Controls and Procedures

|

305

|

|

A. Disclosure Controls and Procedures

|

305

|

|

B. Management’s Annual Report on Internal Control Over

Financial Reporting

|

305

|

|

C. Attestation Report of the Registered Public Accounting

Firm

|

306

|

|

D. Changes in Internal Control Over Financial

Reporting

|

306

|

|

Item 16. Reserved

|

306

|

|

Item 16A. Audit Committee Financial Expert

|

306

|

|

Item 16B. Code of Ethics

|

306

|

|

Item 16C. Principal Accountant Fees and Services

|

306

|

|

Item 16D. Exemption from the Listing Standards for Audit

Committees

|

307

|

|

Item 16E. Purchases of Equity Securities by the Issuer and

Affiliated Purchasers

|

307

|

|

Item 16F. Change in Registrant’s Certifying

Accountant

|

308

|

|

Item 16G. Corporate Governance

|

308

|

|

Item 16H. Mine Safety Disclosures

|

310

|

|

Part III

|

311

|

|

Item 17. Financial Statements

|

311

|

|

Item 18. Financial Statements

|

311

|

|

Item 19. Exhibits

|

311

|

An

investment in our American Depositary Shares (“ADSs”)

and common shares is subject to a number of risks, including risks

relating to Argentina, Brazil, other countries where we operate,

our agricultural business, IRSA’s business in Argentina, our

investment in Banco Hipotecario, our business in the United States,

our Operations Center in Israel and our ADSs and common shares. The

following list summarizes some, but not all, of these risks. Please

read the information in the section entitled “Risk

Factors” for a more thorough description of these and other

risks.

Risks Relating to Argentina, Brazil and other Countries Where We

Operate

●

The ongoing

COVID-19 pandemic and government measures to contain the virus are

adversely affecting our business and results of

operations.

●

Governments in the

countries where we operate or intend to operate exercise

significant influence over their economies.

●

Continuing high

rates of inflation, uncertainty with regard to other economic

indicators and a depreciation of the currencies of the countries in

which we operate may have an adverse effect on the economy and our

business, financial condition and results of

operations.

●

Restrictions on

transfers of foreign currency and the repatriation of capital from

Argentina may impair our ability to pay dividends and distributions

and investors may face restrictions on their ability collect

capital and interest payments in connection with corporate bonds

issued by Argentine companies.

●

The imposition of

restrictions on acquisitions of agricultural properties by foreign

nationals may materially restrict the development of our business

and significant environmental regulation may significantly increase

our expenses.

Risks Relating to Our Agricultural Business

●

Fluctuation in

market prices for our agriculture products could adversely affect

our financial condition and results of operations.

●

Unpredictable

weather conditions, pest infestations and diseases may have an

adverse impact on our crop yields and cattle production. We may be

exposed to material losses due to volatile crop prices since a

significant portion of our production is not hedged, and exposed to

crop price risk.

●

Worldwide

competition in the markets for our products could adversely affect

our business and results of operations.

●

Our internal

processes and controls might not be sufficient to comply with the

extensive environmental regulation and current or future

environmental regulations could prevent us from fully developing

our land affect its operations and ability to pay its debt as it

becomes Our level of debt may adversely affect our operations and

our ability to pay our debt as it becomes due.

Risks Relating to IRSA’s Business in Argentina

●

Disease outbreaks

or other public health concerns could reduce traffic in

IRSA’s shopping malls.

●

IRSA is subject to

risks inherent to the operation of shopping malls that may affect

its profitability. The loss of tenants or the failure of tenants to

comply with the terms of their leases could adversely affect

IRSA’s operating revenues and value of our

properties.

●

The increasingly

competitive real estate sector in Argentina may adversely affect

IRSA’s ability to rent or sell office space and other real

estate.

●

IRSA’s level

of debt may adversely affect its operations and ability to pay its

debt as it becomes due.

Risks Relating to IRSA’s Investment in Banco

Hipotecario

●

COVID-19 may

negatively impact the operations and financial situation of Banco

Hipotecario.

●

The short-term

structure of Banco Hipotecario’s deposit base could lead to a

reduction in liquidity levels and limit the long-term expansion of

financial intermediation.

●

Banco Hipotecario

operates in a highly regulated environment and its operations are

subject to capital controls regulations adopted by several

regulatory agencies.

Risks Relating to IRSA’s Operations Center in

Israel

●

IDB Development

Corporation Ltd. (“IDBD”) was declared insolvent and is

in process of liquidation.

●

Capital

contributions to IDBD and any such capital

contributions may be subject to claims by

creditors.

Risks Relating to our ADSs and Common Shares

●

Common shares

eligible for sale could adversely affect the price of our common

shares and ADSs.

●

If we issue

additional equity securities in the future, you may suffer

dilution, and trading prices for our equity securities may

decline.

●

We are subject to

certain different corporate disclosure requirements and accounting

standards than domestic issuers of listed securities in the United

States.

●

Investors may not

be able to effect service of process within the U.S., limiting

their recovery of any foreign judgment.

●

If we are

considered to be a passive foreign investment company for United

States federal income tax purposes, U.S. holders of our common

shares or ADSs would suffer negative consequences.

●

Holders of the ADS

may be unable to exercise voting rights with respect to the common

shares underlying their ADSs.

●

Under Argentine

law, shareholder rights may be fewer or less well defined than in

other jurisdictions and our ability to pay dividends is limited by

law and our by-laws.

●

Restrictions on the

movement of capital out of Argentina may impair your ability to

receive dividends and distributions on, and the proceeds of any

sale of, the common shares underlying the ADSs.

●

You might be unable

to exercise preemptive or accretion rights with respect to the

common shares underlying your ADSs.

DISCLAIMER REGARDING FORWARD-LOOKING STATEMENTS

This

annual report includes forward-looking statements, principally

under “Risk Factors,” “Information on the

Company” and “Operating and Financial Review and

Prospects.” We have based these forward-looking statements

largely on our current beliefs, expectations and projections about

future events and financial trends affecting our business. Many

important factors, in addition to those discussed elsewhere in this

annual report, could cause our actual results to differ

substantially from those anticipated in our forward-looking

statements, including, among other things:

Factors

that could cause actual results to differ materially and adversely

include but are not limited to:

●

changes in general

economic, financial, business, political, legal, social or other

conditions in Argentina, Brazil, Latin America or Israel or changes

in developed, emerging markets or either;

●

changes in capital

markets in general that may affect policies or attitudes toward

lending to or investing in Argentina or Argentine companies,

including volatility in domestic and international financial

markets;

●

inflation and

deflation;

●

ongoing economic

impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on the Argentine

economy;

●

measures adopted by

the Argentina Government in response to the COVID-19

pandemic;

●

impact on our

business of the COVID-19 pandemic;

●

economic

consequences of the pandemic and the related impact on our buinsess

and financial condition;

●

fluctuations in the

exchanges rates of the peso and in the prevailing interest

rates;

●

increases in

financing costs or our inability to obtain additional financing on

attractive terms, which may limit our ability to fund existing

operations and to finance new activities;

●

current and future

government regulation and changes in law or in the interpretation

by Argentine courts;

●

price fluctuations

in the agricultural and real estate market;

●

political, civil

and armed conflicts;

●

adverse legal or

regulatory disputes or proceedings;

●

fluctuations and

declines in the aggregate principal amount of Argentine public debt

outstanding, default of sovereign debt;

●

government

intervention in the private sector and in the economy, including

through nationalization, expropriation, labor regulation or other

actions;

●

restrictions on

transfer of foreign currencies and other exchange

controls;

●

increased

competition in the shopping mall sector, office or other commercial

properties and related industries;

●

potential loss of

significant tenants at our shopping malls, offices or other

commercial properties;

●

our ability to take

advantage of opportunities in the real estate market of Argentina

or Israel on a timely basis;

●

restrictions on

energy supply or fluctuations in prices of utilities in the

Argentine market;

●

our ability to meet

our debt obligations;

●

shifts in consumer

purchasing habits and trends;

●

technological

changes and our potential inability to implement new

technologies;

●

deterioration in

regional, national or global businesses and economic

conditions;

●

changes on the

applicable regulations to currency exchange or

transfers;

●

incidents of

government corruption that adversely impact the development of our

real estate projects;

●

fluctuations and

declines in the exchange rate of the peso, the U.S. dollar against

other currencies; and

●

risks related to

our investment in Israel; and

●

the risk factors

discussed under “Risk Factors.”

You can

identify forward-looking statements because they contain words such

as “believes,” “expects,”

“may,” “will,” “should,”

“seeks,” “intends,” “plans,”

“estimates,” “anticipates,”

“could,” “target,” “projects,”

“contemplates,” “potential,”

“continue” or similar expressions. Forward-looking

statements include information concerning our possible or assumed

future results of operations, business strategies, financing plans,

competitive position, industry environment, potential growth

opportunities, the effects of future regulation and the effects of

competition. Forward-looking statements speak only as of the date

they were made, and we undertake no obligation to update publicly

or to revise any forward-looking statements after we distribute

this annual report because of new information, future events or

other factors. In light of the risks and uncertainties described

above, the forward-looking events and circumstances discussed in

this annual report might not occur and are not guarantees of future

performance.

You

should not place undue reliance on such statements which speak only

as of the date that they were made. These cautionary statements

should be considered in connection with any written or oral

forward-looking statements that we might issue in the

future.

AVAILABLE INFORMATION

We file

annual and current reports and other information with the United

States Securities and Exchange Commission (“SEC”). You

may obtain any report, information or other document we file

electronically with the SEC at the SEC’s website

(http://www.sec.gov)

or at our website (http://www.cresud.com.ar).

The information contained in our website does not form part of this

annual report.

PRESENTATION OF FINANCIAL AND CERTAIN OTHER

INFORMATION

In this

annual report (the “Annual

Report”), references to “Cresud,” the

“Company,” “we,” “us” and

“our” means Cresud Sociedad Anónima Comercial,

Inmobiliaria, Financiera y Agropecuaria, and its consolidated

subsidiaries, unless the

context otherwise requires, or where we make clear that such term

refers only to Cresud and not to its

subsidiaries.

The

terms “Argentine government” and

“government” refer to the federal government of

Argentina, the terms “Central Bank” ans

“BCRA” refer to the Banco Central de la República

Argentina (the Argentine Central Bank), the terms

“CNV” and “CNV Rules” refer to the

Comisión Nacional de Valores (the Argentine National

Securities Commission) and the rules issued by the CNV,

respectively. In this annual report, when we refer to

“peso,” “pesos” or “ARS” we

mean Argentine pesos, the legal currency of Argentina; when we

refer to “U.S. dollar,” “U.S. dollars” or

“USD” we mean United States dollars, the legal currency

of the United States; when we refer to “Real,”

“Reals,” “Rs.” or “BRL” we mean

Brazilian Real, the legal currency Brazil; and when we refer to

“shekels” or “NIS” we mean Israeli new

shekels, the legal currency of Israel.

References to

“ADSs” are to the American Depositary Shares, each

representing 10 shares of our common stock, issued pursuant to the

deposit agreement, dated as of March 18, 1997 (the “deposit

agreement”), between us, The Bank of New York, as depositary

(the “ADS Depositary”), and the owners and holders of

the ADRs issued from time to time thereunder, and references to

“ADRs” are to the American Depositary Receipts, which

represent the ADSs.

Financial Statements

We

prepare and maintain our financial books and records in pesos and

in conformity with International Financial Reporting Standards

(“IFRS”), as issued by the International Accounting

Standards Board (“IASB”), and the CNV Rules. Our fiscal

year begins on July 1 and ends on June 30 of each

year.

Our audited consolidated financial statements as of

June 30, 2020 and 2019 and for the years ended June 30, 2020, 2019

and 2018, and the notes thereto (our “Audited Consolidated

Financial Statements”) are set forth on pages F-1 through F-

113 of this Annual Report.

Our

Audited Consolidated Financial Statements have been approved by resolution of the Board

of Directors’ meeting held on September 25, 2020 and have

been audited by Price Waterhouse & Co S.R.L., Argentina, member

of PriceWaterhouseCoopers International Limited, an independent

registered public accounting firm whose report is included

herein.

Functional and Presentation

Currency; Adjustment for Inflation

Our functional and presentation currency is the

peso, and our Audited Consolidated Financial Statements included in this Annual

Report are presented in pesos.

IAS 29,

Financial Reporting in

Hyperinflationary Economies (“IAS 29”) requires

that the financial statements of an entity whose functional

currency is one of a hyperinflationary economy be measured in terms

of the current unit of measurement at the closing date of the

financial statements, regardless of whether they are based on the

historical cost method or the current cost method. This requirement

also includes the comparative information of the financial

statements.

In

order to conclude that an economy is

“hyperinflationary,” IAS 29 outlines a series of

factors, including the existence of an accumulated inflation rate

in three years that is approximately or exceeds 100%. As of July 1,

2018, Argentina reported a cumulative three-year inflation rate

greater than 100% and therefore financial information published as

from that date should be adjusted for inflation in accordance with

IAS 29. Therefore, our Audited

Consolidated Financial Statements and the financial information

included in this Annual Report have been stated in terms of the

measuring unit current at the end of the reporting year. For more

information, see section “Financial Statements” above

and Note 2.1 to our Audited Consolidated Financial

Statements.

Effective July 1,

2019, we adopted IFRS 16 “Leases” which establishes the

criteria for recognition and valuation of leases for lessees and

lessors. The changes incorporated mainly impact the tenant's

accounting. IFRS 16 provides that the lessee recognizes an asset

for the right of use and a liability at present value with respect

to those contracts that meet the definition of lease agreements

according to IFRS 16. In accordance with the standard, a lease

agreement is one that provides the right to control the use of an

identified asset for a specific period. In order for a company to

have control over the use of an identified asset: a) it must have

the right to obtain substantially all the economic benefits of the

identified asset and b) it must have the right to direct the use of

the identified asset. The standard allows excluding the short-term

contracts (under 12 months) and those in which the underlying asset

has low value, such option has been adopted by the Company.

Likewise, the Company has opted to recognize as consideration for

the right of use, the amount of ARS 16,797 million as lease

liabilities. The commitments under operating leases reported in

Audited Consolidated Financial Statements as of June 30, 2019,

amounted to ARS 18,395 million (such difference mainly corresponds

to the effect of the discount from future payments and the excluded

short-term contracts).

Additionally, in

accordance with the amendment to IAS 28, an entity shall implement

the provisions of IFRS 9 to Long-term Investments that are

essentially part of the entity's net investment in the associate or

in the joint venture according to the definitions of said standard.

The provisions of IFRS 9 shall apply to such investments with

respect to the participation in the losses of an associate or a

joint venture, as well as with respect to the recognition of the

impairment of an investment in an associate or joint venture. In

addition, when applying IFRS 9 to such long-term investments, the

entity will make it prior to the adjustments made to the carrying

amount of the investment in accordance with IAS 28. We opted for an

accounting policy where the currency translation adjustments

arising from these loans are recorded as part of other

comprehensive income.

See

Note 2.2 to our Audited Consolidated Financial Statements for a

more comprehensive discussion of the effects of the adoption of

these new standards.

Financial Information of our Subsidiaries in Israel

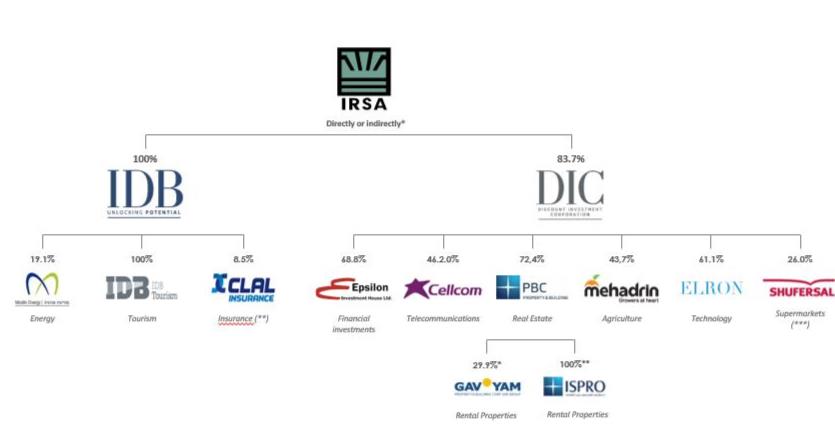

IDB

Development Corporation Ltd. (“IDBD”) and Discount

Investment Corporation (“DIC”), our principal

subsidiaries in the Operations Center in Israel, report their

quarterly and annual results following Israeli regulations, whose

filing deadlines fall after the filing deadlines in Argentina. In

addition, IDBD and DIC’s fiscal year-ends differ from our

fiscal year-end, consequently, we consolidate the results of

operations from IDBD and DIC on a three-month lag basis adjusted

for the effects of any significant transactions taking place within

such period. As such, our audited consolidated statement of

income and other

comprehensive income for the fiscal year ended June 30, 2020

includes the results of IDBD and DIC for the twelve-month period

from April 1, 2019 to March 31, 2020, adjusted for the significant

transactions that occurred between April 1, 2020 and June 30,

2020.

IDBD

and DIC have certain restrictions and financial agreements in

relation to their financial debt, including their bonds and loans

with banks and financial institutions. Regarding IDBD's financial

position, its cash flow and its ability to meet its financial debt

commitments, the following should be considered:

As of June

30, 2020, IDBD had a deficit in shareholders’ equity, ongoing

negative cash flows from continuing operating activities and a low

credit rating, which circumstance may cast significant doubt about

IDBD’s ability to continue operating as a going concern.

IDBD’s cash flow required to meet its liabilities, including

short-term liabilities is based on the realization of assets which

the realization date is not under IDBD’s control. These

assets include the current price of Clal’s shares and the

impact thereof on swap transaction deposits and the fact that IDBD

shall receive, among others, the proceeds from the sale of private

investments which are directly owned by IDBD.

As of

June 30, 2020, the aggregate principal amount of the (i) IDBD

Series 9 Bonds was NIS 901 million (“Series 9”), (ii)

IDBD Series 14 Bonds was NIS 889 million collateralized by DIC

shares owned directly or indirectly by IDBD representing 70% of the

share capital of DIC (“Series 14”), (iii) IDBD Series

15 Bonds was NIS 238 million collateralized by shares of Clal

representing 5% of the share capital of Clal (“Series

15”).

In July 2019

and in June 2020, each of debenture holders (Series 9 and Series

14) and debenture holders (Series 15), respectively, decided to

appoint a representative and legal and economic advisor, inter

alia, in order to maintain contact with IDBD and / or third parties

and to examine proposals that will be presented to the bondholders

in connection with the repayment of IDBD's obligations towards the

bondholders and to evaluate IDBD’s financial position and the

remedies which may be available to the debenture

holders.

In June

2020, general meetings of the holders of IDBD's debentures were

convened (all of the series, each series separately), where a

resolution on the agenda was not to convene a general meeting on

the agenda of which would be the making of the debentures repayable

immediately. The meetings of the debenture holders (Series 9 and

Series 15), each decided to pass the said resolution; The meeting

of the debenture holders (Series 14), decided not to pass the said

resolution, and a later stage to instruct the trustee for debenture

holders (Series 14) to postpone the date of the said meeting to

September 17, 2020;

In July 2020,

Dolphin Netherlands and the controlling interest therein, Mr.

Eduardo Elsztain committed vis-à-vis the generality of the

debenture holders in IDBD, that subject to defined terms and

conditions, during a certain period of time, some transactions will

not be executed and/or initiated and/or promoted, and that subject

to the provisions of the law, the power of control in corporations

that are controlled by the controlling interest in IDBD will not be

operated in order to promote any of those actions, unless

notification has been delivered in writing to the trustees for

debenture holders (Series 9, 14 and 15), at least 14 business days

in advance.

On

August 31, 2019, IDBD 's Audit Committee and the Board of Directors

approved the acceptance of an irrevocable commitment by Dolphin

Netherlands B.V. (“Dolphin Netherland”), the

controlling interest in IDBD, to make capital injections into IDBD

in an overall amount of NIS 210 million, in three equal annual

payments on September 2 in each of the years 2019 to 2021, which

would be made in consideration for shares in IDBD or as a

subordinated loan on similar terms to the subordinated loans that

had been provided by the controlling interest.

In

August 2020, IDBD received a letter from Dolphin Netherlands

stating, inter alia, that given the fact that some of IDBD's

bondholders are expected to include in their agenda for the

bondholder's meetings, a proposal to make the outstanding balances

of their bonds immediately due and payable, in preparation for the

additional inflow of NIS 70 million scheduled for September 2,

2020, Dolphin Netherlands would examine its undertaking towards

IDBD, taking into account the questions that arise from

IDBD’s bondholders conducts and intentions. To the said

Dolphin Netherlands' letter was attached a letter from IRSA to

Dolphin Netherlands, according to which, among other things, IRSA

will consider the validity of its undertaking to Dolphin

Netherlands to transfer to it (in accordance with Dolphin

Netherlands request) the amounts required for Dolphin Netherlands

to meet its commitment to carry out the capital injections into

IDBD on September 2, 2020, as aforementioned.

IDBD

responded to Dolphin Netherlands’ and IRSA’s letters,

noting that, among other things, Dolphin Netherlands' commitment

(dated August 29, 2019) towards IDBD is binding and irrevocable,

and that there is no basis for not making the capital injections

into IDBD, due to other events related to IDBD’s bondholders,

which do not fall within the scope of the events listed in the

wording of the commitment as expropriating the validity of Dolphin

Netherlands' commitment. In addition, it was also mentioned in

IDBD’s response letter, that failure to make the payments

into IDBD is not acceptable and will leave IDBD with no other

choice than to use all its power and rights according to the law to

enforce Dolphin Netherlands' commitment as well as IRSA’s

undertaking.

Following the above

mentioned, on September 13, 2020, IDBD submitted a statement of

claim against Dolphin Netherlands and against IRSA, in which it has

sought to require them to pay it an amount of NIS 70 million (with

the addition of linkage differentials and interest in accordance

with the law). In tandem with the submission of the lawsuit, as

aforesaid, IDBD submitted an urgent petition for placing temporary

attachments (in the presence of one party) on Dolphin Netherlands

and IRSA (which was not accepted by the Court in the presence of

one party and which has been passed on for the respondents to

respond to the petition).

On June

2, 2020, IDBD received a draft proposal from Dolphin IL for IDBD

and for the trustees for IDBD’s debentures (Series 9, 14 and

15) for the strengthening of IDBD 's capital structure, by way of

an arrangement between Dolphin, IDBD and the debenture holders,

based on an economic contribution to IDBD on Dolphin IL's part,

together with a full or partial (as the case may be) redemption of

the generality of IDBD's debentures; On June 21, 2020, IDBD

received an updated proposal in relation to the abovementioned

proposal and on June 28, 2020, Dolphin IL approached each of the

trustees for the debentures with a request to put said proposal,

with slight amendments, on the agenda of meetings of the debenture

holders.

On July

6, 2020, the Meeting of debenture holders (Series 9) decided to

order the trustee for debenture holders (Series 9) not to accept

Dolphin IL's offer; On July 7, 2020, the Meeting of the debenture

holders (Series 14) decided to negotiate for a fixed period of one

month in connection with Dolphin IL's proposal, and on July 8,

2020, the Meeting of debenture holders (Series 15) made a similar

decision.

On

September 2, 2020 IDBD received an updated offer from Dolphin IL

which was addressed to it and to IDBD’s debenture holders

(Series 9, 14 and 15); On September 9, 2020, Dolphin IL updated the

commercial terms of its proposal for debenture holders (Series 9),

and on September 16, 2020, IDBD received binding offers to

debenture holders (Series 14) and debenture holders (Series 15),

for the purchase of DIC shares pledged in favor of debenture

holders (Series 14) of IDBD, as part of an agreed realization

process.

As no

agreement has been reached, on September 17, 2020, the Series 9

trustee submitted to the District Court in Tel-Aviv-Jaffa (the

"Court") a petition to grant an order for the opening of

proceedings for IDBD pursuant to the Insolvency and Economic

Rehabilitation Law, 5778 – 2018 and to instruct the

appointment of a trustee for IDBD pursuant to Section 43 and to

grant the trustee any and all authority over the decision making of

IDBD.

On

September 21, 2020, the Series 14 bond holders approved the

immediate fully payment of the remaining balances of such

serie.

On

September 22, 2020, IDBD and Dolphin Netherlands B.V. submitted an

initial response to the Petition, arguing that it is in the best

interest of IDBD and its creditors to exhaust the negotiations

among the controlling shareholder and its creditors during a short

period with the aim to maximize the value of its assets, avoid

costs and additional negative effects.

In

addition, responses by the Series 14 trustee and the Series 15

trustee were filed requesting the enforcement of liens and the

appointment of a receiver as well as an urgent hearing, which was

scheduled for September 24, 2020.

On

September 25, 2020, the Court resolved that IDBD is insolvent and

therefore it resolved to grant all three orders requested and

accordingly, issued an order for the initiation of proceedings and

liquidation of IDBD, and has appointed a liquidator to IDBD and

interim receivers over the Pledged DIC and Clal

Shares.

Under

IFRS 10 “Consolidated Financial Statements”

(“IFRS 10”), an investor controls an investee if and

only if the investor has all the following: a) power over the

investee; b) exposure, or rights, to variable returns from its

involvement with the investee; and c) the ability to use its power

over the investee to affect the amount of the investor’s

returns. Based on the facts and circumstances outlined above, our

management believe that, as from September 25, 2020, IRSA lost

control over IDBD and DIC (as this term is defined by IFRS 10).

Accordingly, our investment in IDBD and DIC will be deconsolidated

in our financial statements as of and for the three-month period

ended September 30, 2020.

As of the

date of this Annual Report, we are analyzing together with our

local and international advisors the judicial decision,

alternatives and course of action. For more information see

“IRSA´s Recent Developments - Corporate Information:

IDBD”.

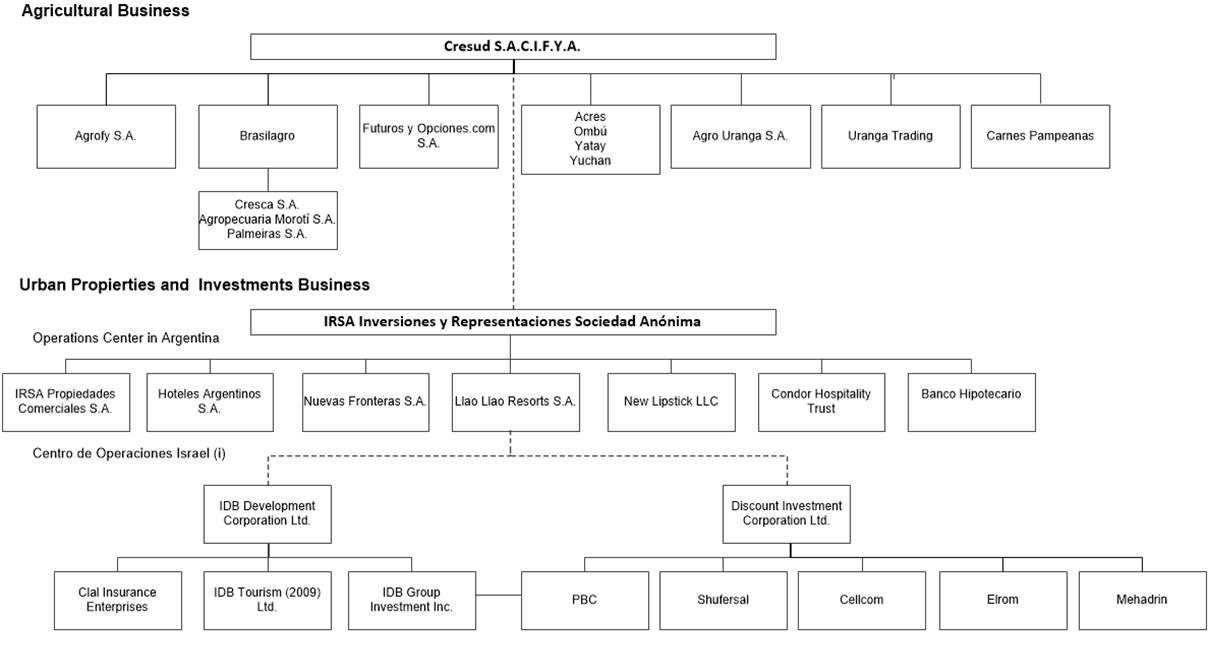

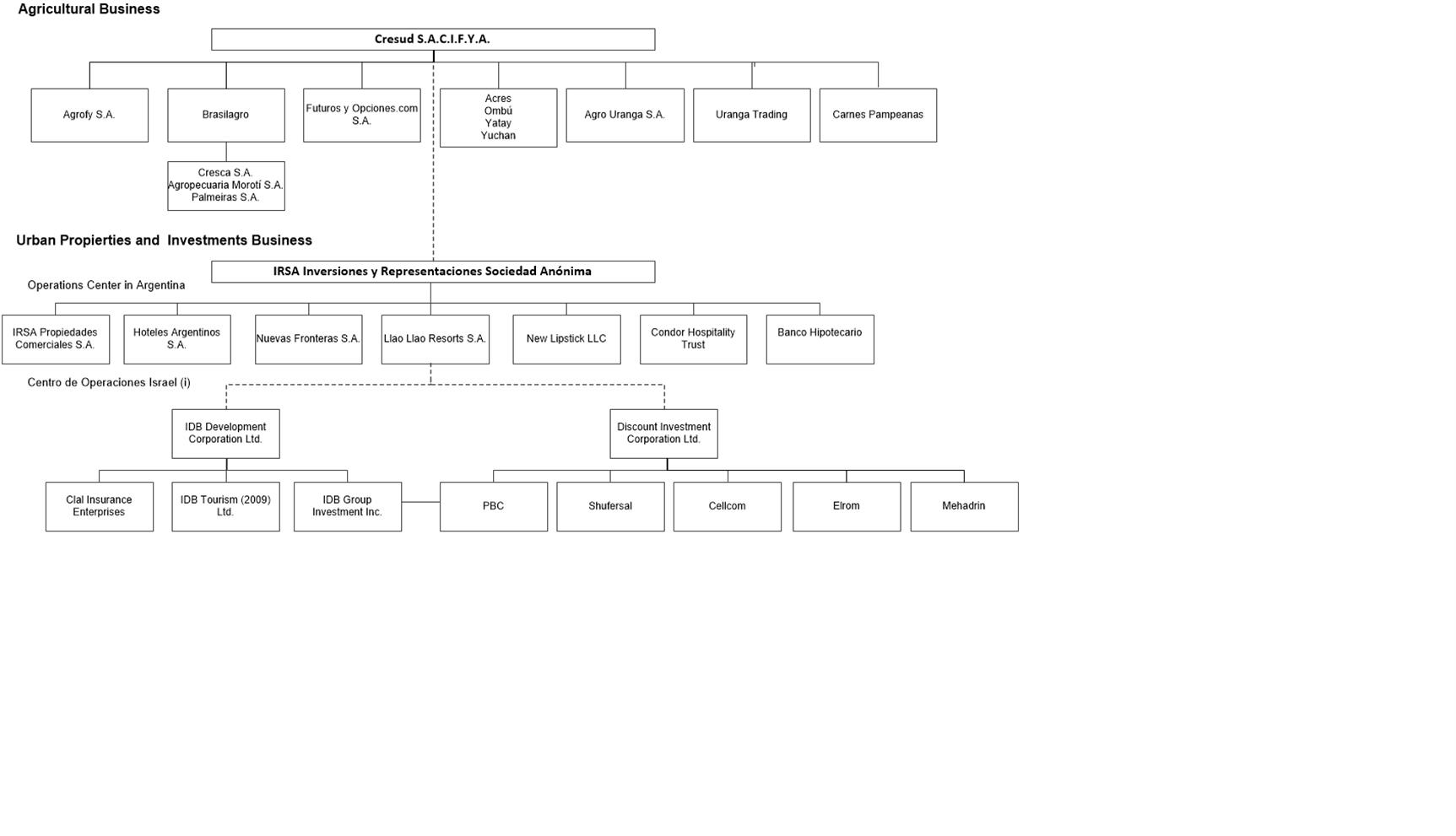

Organizational Structure

As of

June 30, 2020, the Company had two business lines to manage its

global business, which we refer to in this Annual Peport as

“Agricultural Business” and “Urban Properties and

Investments Business” derived from our subsidiary IRSA, which

is in turn subdivided into two operations centers which we refer as

the “Operations Center in Argentina” and the

“Operations Center in Israel.”

(i)

See

“—Financial Information of our Subsidiaries in

Operation Center in Israel.”

Currency Translations

We have

translated some of the peso amounts contained in this annual report

into U.S. dollars for convenience purposes only. Unless otherwise

specified or the context otherwise requires, the rate used to

convert peso amounts to U.S. dollars is the seller exchange rate

quoted by Banco de la Nación Argentina of ARS 70.4600 per USD

1.00 for information provided as of June 30, 2020. The average

seller exchange rate for fiscal year 2020, quoted by Banco de la

Nación Argentina was ARS 59.5343. The U.S. dollar-equivalent

information presented in this annual report is provided solely for

the convenience of the reader and should not be construed as

implying that the peso amounts represent, or could have been or

could be converted into, U.S. dollars at such rates or at any other

rate. The seller exchange rate quoted by Banco de la Nación

Argentina was ARS 79.7500 per USD1.00 as of November 13, 2020. See

“Local Exchange Market and Exchange Rates” and

“Risk Factors—Risks relating to

Argentina—Continuing high rates of inflation may have an

adverse effect on the economy and our business, financial condition

and the results of our operations.”

We have

also translated certain NIS amounts into U.S. dollars at the offer

exchange rate for June 30, 2020 which was NIS 3.4619 per USD 1.00.

We make no representation that the peso, NIS or U.S. dollar amounts

actually represent or could have been or could be converted into

U.S. dollars at the rates indicated, at any particular rate or at

all. See “Local Exchange Market and Exchange

Rates.”

Market Share Data

Information

regarding market share in a specified region or area is based on

data compiled by us from internal sources and from publications

such as Bloomberg, the International Council of Shopping Centers,

the Argentine Chamber of Shopping Centers (Cámara Argentina de Shopping

Centers), and the INDEC.

Certain Measurements

In

Argentina the standard measure of area in the real estate market is

the square meter (m2), while in the

United States and certain other jurisdictions the standard measure

of area is the square foot (sq. ft.). All units of area shown in

this annual report (e.g.,

gross leasable area of buildings (“GLA” or “gross

leasable area”), and size of undeveloped land) are expressed

in terms of square meters (“sqm” and “m2”).

One square meter is equal to approximately 10.8 square feet. One

hectare is equal to approximately 10,000 square meters and to

approximately 2.47 acres.

In

Argentina the standard measure of weight are the tons (“Tons,” “tons” or

“Tns”) and kilograms (“kg” or

“kgs”), while in the United States and certain

other jurisdictions the standard measure of weight are the pound or

the bushel. A metric ton is equal to

1,000 kilograms. A kilogram is equal to approximately 2.2 pounds. A

metric ton of wheat is equal to approximately 36.74 bushels. A

metric ton of corn is equal to approximately 39.37 bushels. A

metric ton of soybean is equal to approximately 36.74 bushels. One

kilogram of live weight cattle is equal to approximately 0.5 to 0.6

kilogram of carcass (meat and bones).

As used

herein, GLA in the case of shopping malls refers to the total

leasable area of the property, regardless of our ownership interest

in such property (excluding common areas and parking and space

occupied by supermarkets, hypermarkets, gas stations and co-owners,

except where specifically stated).

Rounding Adjustments

Certain

numbers and percentages included in this annual report have been

subject to rounding adjustments. Accordingly, figures shown for the

same category presented in various tables or other sections of this

annual report may vary slightly, and figures shown as totals in

certain tables may not be the arithmetic aggregation of the figures

that precede them.

PART I

Item 1. Identity of Directors, Senior Management and

Advisers

This

item is not applicable.

Item 2. Offer Statistics and Expected Timetable

This

item is not applicable.

Item 3. Key Information

A. SELECTED CONSOLIDATED FINANCIAL DATA

The following table presents our selected financial data as of June

30, 2020, 2019 and 2018 and for the fiscal years ended June 30,

2020, 2019, 2018 and 2017. The selected consolidated statement of

income and other comprehensive income data and the selected

consolidated statement of cash flow data for the fiscal years ended

June 30, 2020, 2019 and 2018 and the selected consolidated

statement of financial position data as of June 30, 2020 and 2019

have been prepared in accordance with IFRS, as issued by the IASB,

and CNV Rules, and have been derived from our Audited Consolidated

Financial Statements included in this Annual Report.

The summary consolidated statement of income and other

comprehensive income and cash flow data for the fiscal year ended

June 30, 2017 and the summary consolidated statement of financial

position data as of June 30, 2018 have been restated pursuant to

IAS 29 to reflect the effect of hyperinflation in Argentina. As a

result of such restatement, the selected financial information

included in this Annual Report differ from previously reported

financial information.

The summary financial data as of June 30, 2017 and 2016 and for the

fiscal year ended June 30, 2016 has not been presented as these

cannot be provided on a restated basis without unreasonable effort

or expense. See “Presentation of Financial and Other

Information—Functional and Presentation Currency,”

“Risk Factors—Risk Related to Argentina,”

“Operating and Financial Review and Prospects—Results

of Operations— Effects of Changes in Inflation” and

Note 2 to our Audited Consolidated Financial

Statements.

You should read the information below in conjunction with our

Audited Consolidated Financial Statements, including the notes

thereto.

In the following table, we have translated peso amounts into U.S.

dollars at the seller exchange rate as of June 30, 2020, quoted by

the Banco de la Nación Argentina, which was ARS 70.4600 per

USD 1.00. The average of the seller exchange rate for the fiscal

year 2020, quoted by Banco de la Nación Argentina was ARS

59.5343. We make no representation that these peso or U.S. dollar

amounts actually represent, could have been or could be converted

into U.S. dollars at the rates indicated, at any particular rate or

at all. See “Local Exchange Market and Exchange Rates”

and “Risk Factors—Risks Relating to

Argentina—Continuing high rates of inflation may have an

adverse effect on the economy and our business, financial condition

and the results of our operations.” For more information see

“Operating and Financial Review and Prospects—Factors

Affecting Comparability of our Results”

|

|

For the fiscal year ended June 30,

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

CONSOLIDATED STATEMENT OF INCOME AND OTHER COMPREHENSIVE INCOME

DATA

|

|

in millions of ARS

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Revenues

|

1,721

|

121,256

|

110,741

|

93,266

|

91,254

|

|

Costs

|

(1,192)

|

(83,971)

|

(75,384)

|

(62,078)

|

(60,302)

|

|

Initial

recognition and changes in the fair value of biological assets and

agricultural products at the point of harvest

|

40

|

2,827

|

2,305

|

1,674

|

253

|

|

Changes

in the net realizable value of agricultural products after

harvest

|

9

|

657

|

(43)

|

532

|

(360)

|

|

Gross profit

|

578

|

40,769

|

37,619

|

33,394

|

30,845

|

|

Net

gain from fair value adjustment of investment

properties

|

440

|

30,992

|

(37,746)

|

18,971

|

(5,259)

|

|

Gain

from disposal of farmlands

|

12

|

838

|

665

|

1,656

|

630

|

|

General

and administrative expenses

|

(174)

|

(12,267)

|

(12,152)

|

(10,876)

|

(11,057)

|

|

Selling

expenses

|

(232)

|

(16,348)

|

(13,976)

|

(13,489)

|

(14,089)

|

|

Impairment

of associates

|

(35)

|

(2,470)

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

|

Other

operating results, net

|

39

|

2,77

|

1,101

|

3,657

|

(567)

|

|

Management

fees

|

(3)

|

(211)

|

-

|

(1,456)

|

(619)

|

|

Profit / (loss) from operations

|

625

|

44,073

|

(24,489)

|

31,857

|

(116)

|

|

Share

of profit of associates and joint ventures

|

123

|

8,662

|

(7,328)

|

(3,452)

|

(1,366)

|

|

Profit / (loss) before financial results and income

tax

|

748

|

52,735

|

(31,817)

|

28,405

|

(1,482)

|

|

Finance

income

|

21

|

1,463

|

1,775

|

1,476

|

1,630

|

|

Finance

cost

|

(365)

|

(25,683)

|

(22,571)

|

(26,377)

|

(20,173)

|

|

Other

financial results

|

(265)

|

(18,667)

|

(5,981)

|

(22,168)

|

13,249

|

|

Inflation

adjustment

|

3

|

177

|

(457)

|

(321)

|

(3,445)

|

|

Financial results, Net

|

(606)

|

(42,710)

|

(15,272)

|

(47,390)

|

(8,739)

|

|

Profit / (loss) before income tax

|

142

|

10,025

|

(47,089)

|

(18,985)

|

(10,221)

|

|

Income

tax

|

(115)

|

(8,107)

|

(780)

|

9,964

|

(2,087)

|

|

Profit / (loss) for the fiscal year from continuing

operations

|

27

|

1,918

|

(47,869)

|

(9,021)

|

(12,308)

|

|

Profit

for the period from discontinued operations

|

257

|

18,085

|

7,140

|

36,441

|

17,485

|

|

Profit / (loss) for the fiscal year

|

284

|

20,003

|

(40,729)

|

27,420

|

5,177

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Other

comprehensive income / (loss):

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Items that may be reclassified subsequently to profit or

loss:

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Currency

translation adjustment

|

74

|

5,232

|

-3,113

|

6,417

|

8,093

|

|

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

|

Revaluation

surplus

|

9

|

614

|

1,111

|

316

|

-

|

|

Change

in the fair value of hedging instruments net of income

taxes

|

(1)

|

(102)

|

19

|

(40)

|

412

|

|

Items that may not be reclassified subsequently to profit or

loss:

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Actuarial

loss from defined benefit plans

|

(2)

|

(137)

|

(66)

|

(60)

|

(26)

|

|

Other comprehensive income / (loss) for the year from continuing

operations

|

80

|

5,607

|

(2,049)

|

6,633

|

8,479

|

|

Other

comprehensive income / (loss) for the year from discontinued

operations

|

82

|

5,810

|

1,245

|

10,059

|

(2,692)

|

|

Total other comprehensive income for the year

|

162

|

11,417

|

(804)

|

16,692

|

5,787

|

|

Total comprehensive income / (loss) for the year

|

446

|

31,420

|

(41,533)

|

44,112

|

10,964

|

|

Total comprehensive income / (loss) from continuing operations

|

107

|

7,525

|

(49,918)

|

(2,389)

|

(3,832)

|

|

Total comprehensive income from discontinued operations

|

339

|

23,895

|

8,385

|

46,501

|

14,796

|

|

Total comprehensive income / (loss) for the year

|

446

|

31,420

|

(41,533)

|

44,112

|

10,964

|

|

Profit / (loss) of the year attributable to:

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Equity

holders of the parent

|

56

|

3,929

|

(26,796)

|

6,106

|

(892)

|

|

Non-controlling

interest

|

228

|

16,074

|

(13,933)

|

21,314

|

6,069

|

|

Loss from continuing operations attributable to:

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Equity

holders of the parent

|

(34)

|

(2,368)

|

(28,334)

|

(9,492)

|

(3,096)

|

|

Non-controlling

interest

|

61

|

4,286

|

(19,535)

|

471

|

(9,212)

|

|

Total comprehensive income attributable to:

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Equity

holders of the parent

|

34

|

2,421

|

(27,078)

|

5,775

|

1,436

|

|

Non-controlling

interest

|

412

|

28,999

|

(14,455)

|

38,337

|

9,528

|

|

|

Fiscal year ended June 30, 2020 (i)(ii)

|

Fiscal year ended June 30, 2020

|

Fiscal year ended June 30, 2019

|

Fiscal year ended June 30, 2018

|

|

Consolidated Statements of Financial Position

|

|

in millions of ARS

|

|

|

|

|

|

ASSETS

|

|

|

|

|

|

Non-current assets

|

|

|

|

|

|

Investment

properties

|

3,267

|

230,167

|

335,016

|

363,675

|

|

Property,

plant and equipment

|

851

|

59,956

|

54,106

|

52,073

|

|

Trading

properties

|

69

|

4,856

|

7,855

|

14,801

|

|

Intangible

assets

|

400

|

28,192

|

26,018

|

27,996

|

|

Right-of-use

assets

|

311

|

21,928

|

-

|

-

|

|

Biological

assets

|

25

|

1,759

|

1,805

|

2,012

|

|

Other

assets

|

-

|

-

|

31

|

417

|

|

Investments

in associates and joint ventures

|

1,066

|

75,128

|

44,870

|

58,192

|

|

Deferred

income tax assets

|

13

|

927

|

772

|

2,610

|

|

Income

tax and minimum presumed income tax (“MPIT”)

credits

|

1

|

63

|

273

|

1,006

|

|

Restricted

assets

|

27

|

1,936

|

4,547

|

4,842

|

|

Trade

and other receivables

|

388

|

27,326

|

21,730

|

20,298

|

|

Investment

in financial assets

|

50

|

3,515

|

4,129

|

3,815

|

|

Financial

assets held for sale

|

-

|

-

|

5,972

|

17,317

|

|

Derivative

financial instruments

|

2

|

164

|

153

|

67

|

|

Total non-current assets

|

6,470

|

455,917

|

507,277

|

569,121

|

|

Current assets

|

|

|

|

|

|

Trading

properties

|

33

|

2,316

|

523

|

7,285

|

|

Right-of-use

assets

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

|

Biological

assets

|

39

|

2,773

|

3,795

|

2,030

|

|

Inventories

|

129

|

9,070

|

6,403

|

5,250

|

|

Restricted

assets

|

88

|

6,209

|

6,261

|

9,446

|

|

Income

tax and minimum presumed income tax (“MPIT”)

credits

|

4

|

306

|

559

|

888

|

|

Groups

of assets held for sale

|

622

|

43,816

|

11,498

|

11,544

|

|

Trade

and other receivables

|

620

|

43,717

|

38,452

|

38,270

|

|

Investment

in financial assets

|

258

|

18,192

|

45,134

|

56,998

|

|

Financial

assets held for sale

|

48

|

3,377

|

16,666

|

9,930

|

|

Derivative

financial instruments

|

5

|

321

|

162

|

344

|

|

Cash

and cash equivalents

|

1,432

|

100,926

|

89,304

|

85,938

|

|

Total current assets

|

3,278

|

231,023

|

218,757

|

227,923

|

|

TOTAL ASSETS

|

9,748

|

686,940

|

726,034

|

797,044

|

|

SHAREHOLDERS’ EQUITY

|

|

|

|

|

|

Share

capital

|

7

|

499

|

486

|

482

|

|

Treasury

shares

|

-

|

3

|

16

|

20

|

|

Inflation

adjustment of share capital and treasury shares

|

139

|

9,786

|

9,786

|

9,786

|

|

Share

premium

|

150

|

10,592

|

10,592

|

10,592

|

|

Additional

paid-in capital from treasury shares

|

1

|

90

|

91

|

91

|

|

Legal

reserve

|

5

|

373

|

373

|

373

|

|

Special

reserve

|

11

|

770

|

5,179

|

5,179

|

|

Other

reserves

|

14

|

1,006

|

36,427

|

6,124

|

|

Retained

earnings

|

29

|

2,040

|

(38,908)

|

20,589

|

|

Equity

attributable to equity holders of the parent

|

356

|

25,159

|

24,042

|

53,236

|

|

Non-controlling

interest

|

1,377

|

96,994

|

103,159

|

123,218

|

|

TOTAL SHAREHOLDERS’ EQUITY

|

1,733

|

122,153

|

127,201

|

176,454

|

|

LIABILITIES

|

|

|

|

|

|

Non-current liabilities

|

|

|

|

|

|

Borrowings

|

4,548

|

320,418

|

397,414

|

416,820

|

|

Deferred

income tax liabilities

|

702

|

49,469

|

57,192

|

59,963

|

|

Trade

and other payables

|

41

|

2,986

|

2,830

|

8,241

|

|

Provisions

|

44

|

3,091

|

11,478

|

7,931

|

|

Employee

benefits

|

6

|

447

|

189

|

244

|

|

Income

tax and minimum presumed income tax ("MPIT")

liabilities

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

|

Derivative

financial instruments

|

216

|

15,194

|

-

|

-

|

|

Lease

liabilities

|

1

|

74

|

1,470

|

89

|

|

Payroll

and social security liabilities

|

4

|

247

|

197

|

169

|

|

Total non-current liabilities

|

5,562

|

391,926

|

470,770

|

493,457

|

|

Current liabilities

|

|

|

|

|

|

Trade

and other payables

|

508

|

35,823

|

32,299

|

40,057

|

|

Borrowings

|

1,396

|

98,389

|

80,384

|

71,336

|

|

Provisions

|

35

|

2,443

|

2,477

|

2,355

|

|

Group

of liabilities held for sale

|

336

|

23,649

|

8,137

|

7,210

|

|

Payroll

and social security liabilities

|

66

|

4,685

|

3,802

|

4,154

|

|

Income

tax and MPIT liabilities

|

12

|

824

|

699

|

1,324

|

|

Lease

liabilities

|

80

|

5,661

|

-

|

-

|

|

Derivative

financial instruments

|

20

|

1,387

|

265

|

697

|

|

Total Current liabilities

|

2,453

|

172,861

|

128,063

|

127,133

|

|

TOTAL LIABILITIES

|

8,015

|

564,787

|

598,833

|

620,590

|

|

TOTAL SHAREHOLDERS’ EQUITY AND LIABILITIES

|

9,748

|

686,940

|

726,034

|

797,044

|

|

|

For the fiscal year ended June 30,

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Consolidated Statements of Cash Flows

|

|

in millions of ARS

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Net

cash generated from operating activities

|

507

|

35,734

|

25,546

|

24,150

|

23,649

|

|

Net

cash generated from / (used in) investing activities

|

572

|

40,311

|

10,552

|

(31,553)

|

(6,623)

|

|

Net

cash used in financing activities

|

(1,031)

|

(72,624)

|

(25,735)

|

(4,009)

|

6,066

|

|

Net

increase / (decrease) in cash and cash equivalents

|

49

|

3,421

|

10,363

|

(11,412)

|

23,092

|

|

Cash

and cash equivalents at beginning of the year

|

1,267

|

89,304

|

85,938

|

73,012

|

48,168

|

|

Cash

and cash equivalents at the end of the year

|

1,432

|

100,926

|

89,304

|

85,938

|

73,012

|

|

|

For the fiscal year ended June 30,

|

|

|

2020

|

2020

|

2019

|

2018

|

|

|

|

USD

|

in millions of ARS (except per share

data)

|

|

Basic net income per share (1)

|

(0.112)

|

(7.867)

|

(54.790)

|

12.290

|

|

|

Diluted net income per share (2)

|

(0.108)

|

(7.634)

|

(54.790)

|

11.820

|

|

|

Basic net income per ADS (1)(3)

|

(1.117)

|

(78.670)

|

(547.900)

|

122.900

|

|

|

Diluted net income per ADS (2)(3)

|

(1.083)

|

(76.340)

|

(547.900)

|

118.200

|

|

|

Capital

stock

|

7

|

502

|

502

|

502

|

|

|

Number

of common shares

|

501,642,804

|

501,642,804

|

501,642,804

|

501,642,804

|

|

|

Weighted

– average number of common shares outstanding

|

493,808,696

|

493,808,696

|

489,067,648

|

496,687,276

|

|

|

Diluted weighted – average number of common

shares (5)

|

513,044,949

|

513,044,949

|

508,783,905

|

516,403,816

|

|

|

Dividends

paid

|

(28)

|

(1,997)

|

(2,138)

|

(4,363)

|

|

|

Dividends

per share

|

(0.06)

|

(4.04)

|

(4.37)

|

(8.78)

|

|

|

Dividends per ADS (3)

|

(0.57)

|

(40.44)

|

(43.72)

|

(87.84)

|

|

|

Depreciation

and amortization

|

253

|

17,797

|

11,405

|

10,241

|

|

|

Capital

expenditure

|

174

|

12,28

|

20,642

|

22,741

|

|

|

Working

Capital

|

825

|

58,162

|

90,694

|

100,79

|

|

|

Gross

margin

|

0.33

|

0.33

|

0.33

|

0.35

|

|

|

Operating

margin

|

0.36

|

0.36

|

(0.22)

|

0.34

|

|

|

Net

margin

|

0.16

|

0.16

|

(0.36)

|

0.29

|

|

|

Ratio

of current assets to current liabilities

|

1.34

|

1.34

|

1.71

|

1.79

|

|

|

Ratio

of shareholders’ equity to total liabilities

|

0.22

|

0.22

|

0.21

|

0.28

|

|

|

Ratio

of non current assets to total assets

|

0.66

|

0.66

|

0.70

|

0.71

|

|

|

Ratio

of “Return on Equity” – ROE

|

0.16

|

0.16

|

(0.27)

|

N/A.

|

|

(i)

Totals may not sum

due to rounding.

(ii)

Solely for the

convenience of the reader we have translated peso amounts into U.S.

dollars at the seller exchange rate quoted by Banco de la

Nación Argentina as of June 30, 2020, which was ARS 70.4600

per USD 1.00. The average seller exchange rate for the fiscal year

2020, quoted by Banco de la Nación Argentina was ARS 59.6343.

The seller exchange rate quoted by Banco de la Nación

Argentina was ARS 79.7500 per USD 1.00 as of November 13, 2020. We

make no representation that the peso or U.S. dollar amounts

actually represent, could have been or could be converted into U.S.

dollars at the rates indicated, at any particular rate or at all.

See “Local Exchange Market and Exchange Rates.” Totals

may not sum due to rounding.

|

(1)

|

Basic

net income per share is computed by dividing the net income

available to common shareholders for the period by the weighted

average common shares outstanding during the period,

|

|

(2)

|

Diluted

net income per share is computed by dividing the net income for the

period by the weighted average number of common shares assuming the

total conversion of outstanding notes and exercise of outstanding

options, Due to the loss for the year 2019, there is no diluted

effect on this result,

|

|

(3)

|

Determined

by multiplying per share amounts by ten (one ADS equals ten common

shares),

|

Local Exchange Market and Exchange Rates

Operations Center in Argentina